Vietnam

One of Dam’s most distinct memories from Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City) is riding on a motorbike with his dad to go and get a chocolate treat. Dam’s father was a farmer, and they lived on a plantation, where they had tropical fruits like durians, mangosteens, and pomelos. (audio below)

Dam’s mother was a housewife but worked as a nurse informally in the community. When Dam was only a few years old, his mom and dad divorced.

Dam’s maternal grandfather studied Political Science in Washington DC in the late 1960s. He returned to Vietnam to work for the Vietnamese government. After the Vietnam War, because of his previous political involvement, he was put in jail for five years by the communist government. When Dam’s grandfather finally escaped, he made his way to the United States through Thailand and the Philippines. Once in the US and settled, he sponsored his wife, his daughter (Dam’s mother) and her two boys (Dam and his brother) to come to Maryland in 1992.

Maryland

Dam was five years old when he arrived in the United States. He remembers that first plane ride and saying goodbye to his grandmother.

“I knew that once we boarded that plane, something would be different.”

It was fall in Montgomery County, Maryland, and extremely cold.

“On the first day of school, I didn’t know an ounce of English, and I wanted to use the restroom. I was looking around, and I didn’t know how to ask. I was trying to tell them in Vietnamese, and no one understood, so I just peed myself right there on the first day. It was embarrassing.” (audio below)

Dam’s first friends in Maryland were the five other students in his ESL (English as a Second Language) class. After arriving in America, his mom did different odd jobs. She was a server at a Vietnamese Pho restaurant for a while; then, she got her nail technician license, a skill she already had learned in Vietnam. With her new husband, whom she had met in the US, she bought a nail salon. Dam’s mother missed Vietnam, but she knew the opportunities were better in America.

“In Vietnam we have a poor country. You work hard, but you cannot make enough money to survive [crying].” (audio below)

Broken

Dam’s mom has a lot of regrets about how things went after moving to the United States. It was her second marriage that she thinks broke her family apart. Dam suffered physical abuse at the hands of his stepfather, and that’s why Dam had to enter the foster care system. Remembering this breaks his mother’s heart.

“He told me every day he cried because he missed me.” (audio below)

From the age of 14 to 21, Dam was in foster care. He attended four different high schools and lived in many group homes and foster homes. After being emancipated at 21, he returned to live with his mom, and they are still working out their issues.

“It was hard. I limited my mom’s visits, ’cause I was upset with her for a while. I’ve been going to therapy.”

Heading South

Dam’s mom never fully adjusted to Maryland’s winters, remarking that “the wind goes through your bones.” She had some friends in South Carolina who kept encouraging her to move south. Dam’s mom couldn’t move though because she needed to be in Maryland to care for her parents. After they passed, she decided to give South Carolina a try. Dam’s mom moved her life to Seneca in 2016.

When she headed south, Dam remained in Maryland, where he was working and studying. Then he had a car accident, which resulted in a herniated disc, and he was dealing with some mental health issues. Dam had no support in Maryland, so he decided to pack everything up and move down to South Carolina to be with his mom.

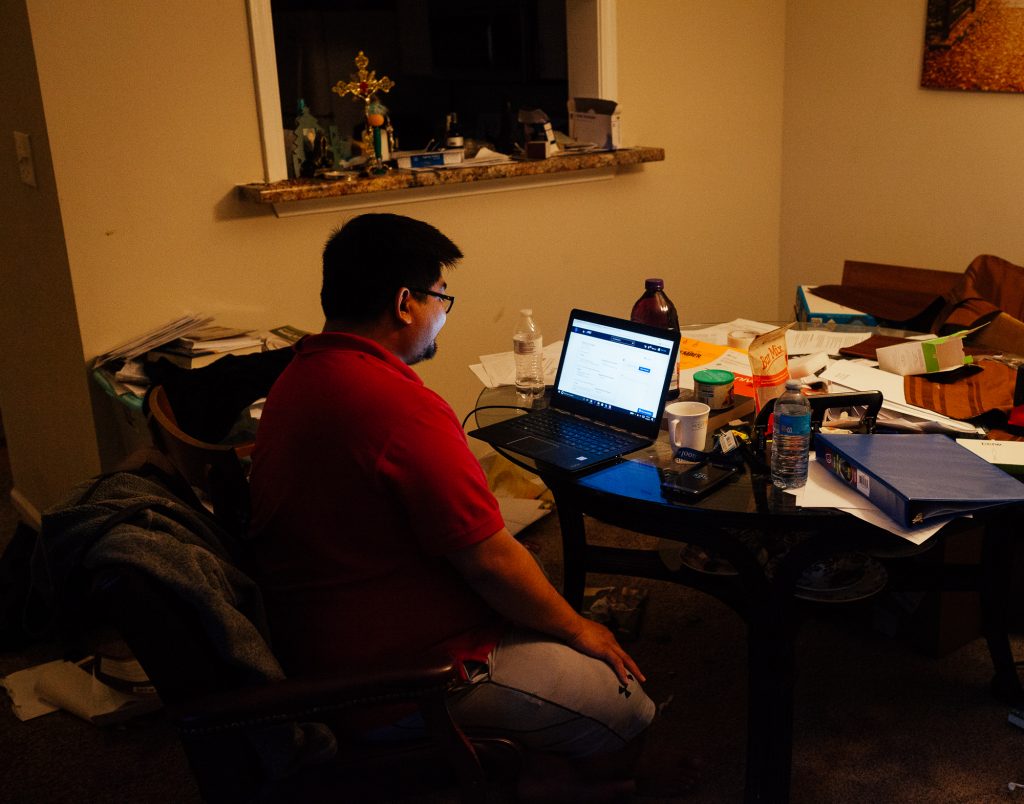

Since moving to Seneca, Dam started doing an online university degree, he is helping his mom with her all of the paperwork for her nail salon, and he is working as a sales associate at the Dollar General. He likes working there because he gets to talk to people from all walks of life.

Dam has always found it difficult making friends and has only made a couple so far in South Carolina.

“I have a hard time making friends due to the walls that I put up. It’s hard trusting people for me because of my time in foster care.”

Volunteering

Shortly after moving to Seneca, Dam started volunteering at the local retirement residence.

“I volunteer here because the residents remind me of my grandparents. I like helping the elderly. It’s sad sometimes, how their kids leave them here, but that is why I have come here to cheer them up.”

Dam has developed a special friendship with many of the residents as well as with the volunteer coordinator Jenna, who appreciates Dam’s help and feels like she has known him for years. (audio below)

Jenna says the residents appreciate how spunky and personable Dam is, and his “very caring heart.” Dam decorated the mantle in the common room, and he has gained a reputation for his Gangnam Style dance moves. The home’s morale is elevated by the presence of people like Dam and Jenna. One of the residents remarked:

“We like where we live. If we didn’t, we’d get the hell out of here!” (audio below)

The South

Dam has noticed how things are different than in Maryland. The people in the South are more direct, life moves at a slower pace, and things are cheaper.

“People are nicer here and want to help you out. They have a nice fakeness. People say hi to you here, while in the northern states, they don’t care.”

He has also noticed the different role religion plays in the “bible belt”. Dam grew up Catholic, has tried being a Methodist, and a Baptist, and now he is a part of a non-denominational church.

“A friend downstairs invited me to his church. I went there, and all of a sudden, I felt the holy spirit and got baptized again. I actually felt it, the first time I got baptized I did it for my family, but this time it was for me.” (audio below)

Most people Dam encounters in Seneca – a town of a little over 8000 people – assume he is Spanish-speaking.

“I’ve had people come up to me and speak Spanish. They just assume. ‘Are you Guatemalan or Honduran?’ They think I am everything but Asian.”

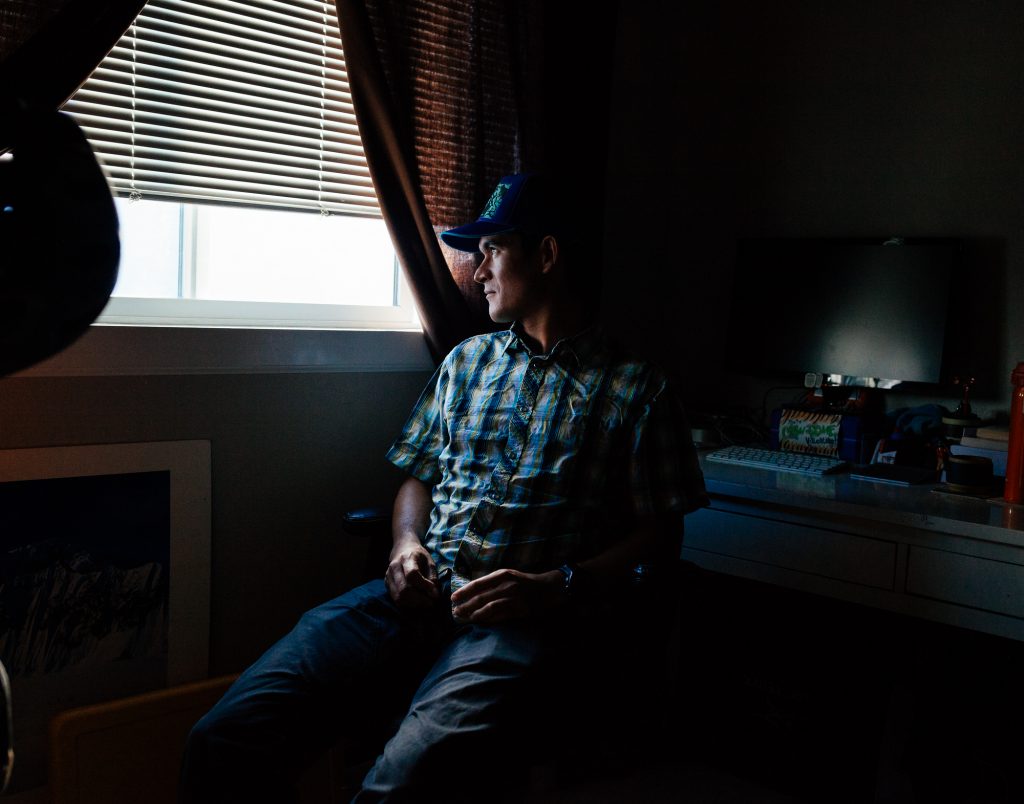

Still, Dam stays connected to his Vietnamese roots. For the holidays, he wears this ozai [see the above photo], and he and his mother make Vietnamese food all the time. His specialties are sweet/sour fish soup, and pho, but the ingredients are hard to find since there aren’t any Asian markets nearby.

Nails

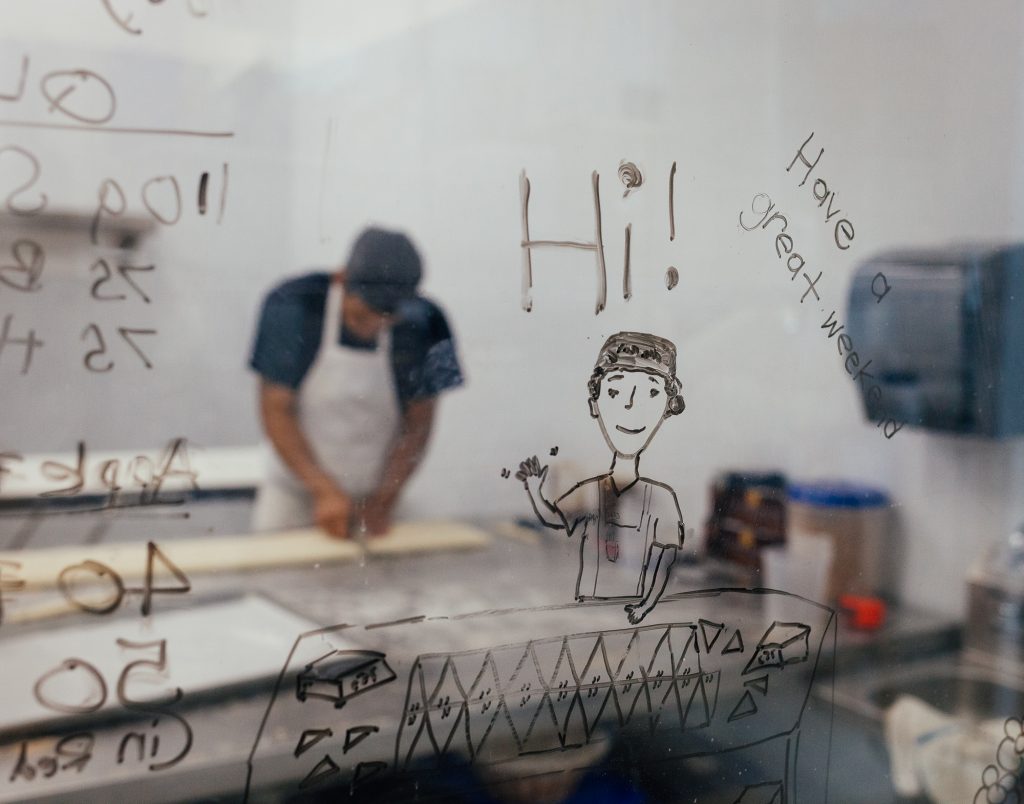

Dam’s mom bought a nail salon inside Seneca’s Walmart and Dam does all of her paperwork and taxes since she still struggles with the language.

“I have been doing nails since I came here to the United States. I learned first in my country. My dad told me to learn how to do nails as it was the fastest way to make money, survive, and be independent.”

Dam’s mom has three sons, and she is proud that her youngest is in the Navy. She was excited to have him home for Thanksgiving.

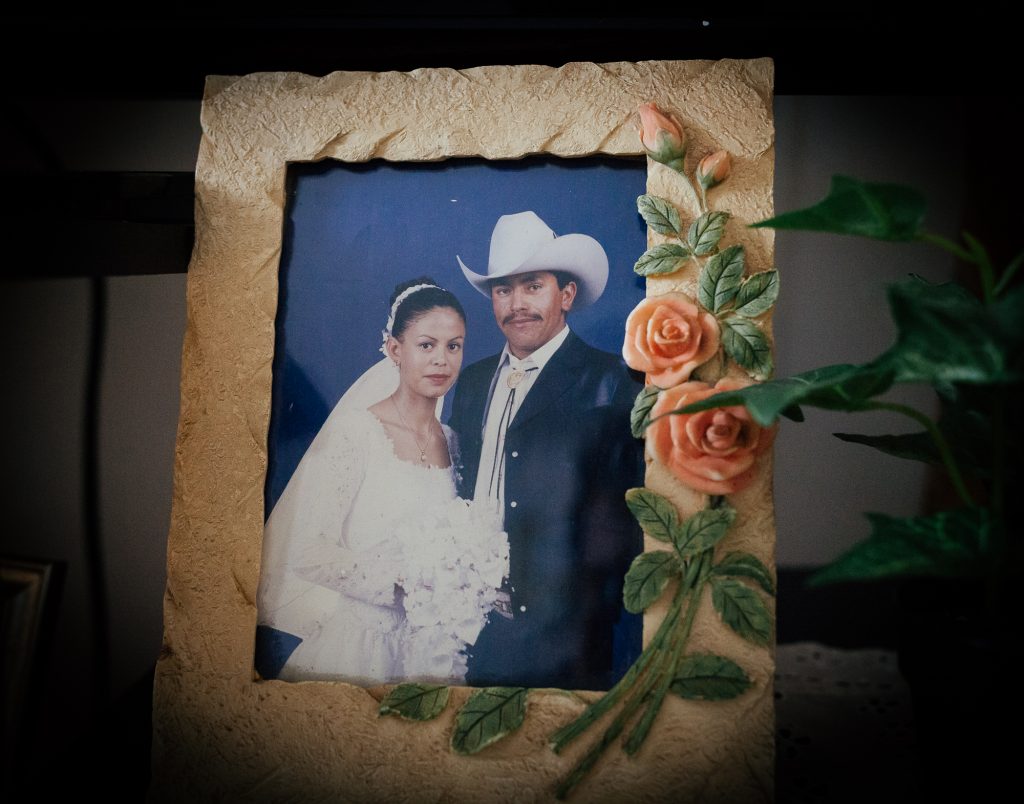

Mom’s Boyfriend

Dam’s mom has found a new boyfriend named Jerry. Dam says he is her “sugar daddy” because he pays for everything. He also says Jerry looks like Colonel Custer from the Civil War but he would never tell him that.

Jerry is a retired Vietnam Vet and a South Carolina local. He has always felt connected to Vietnam and the Vietnamese people.

“I left Vietnam, but it never left me.”

Jerry would walk over to Walmart every morning just for something to do. He noticed Dam’s mom in her nail salon and pursued her.

“I was married when I went to Vietnam. When I came back, my wife had three or four boyfriends. I stayed single all these years. I had a massive heart attack, retired and the veteran’s administration takes care of me now. I’m sure grateful for everything. You can see what the attraction was – big big hugs! How can I not come to visit her every day? Looking at her – that’s easy!” (audio below)

Dam’s mom works so hard most days from nine in the morning to nine at night, so it is impossible for her to meet anyone to date. Luckily she met Jerry, who she calls “honey” because he is so sweet

“Dam says he is a ‘sugar daddy’; I said he is a miracle. God sent somebody to help me. ”

Although they have only known each other for months, Jerry says he was looking for her for 50 years. (audio below)

Future

Dam’s mom is still worried about her son’s physical and mental health, knowing that he has been through a lot. Dam found this place up in the mountains in Westminster called Chatuga Bell Farm with a beautiful view that he likes to go to clear his mind and relax.

“As a kid, you have your castle or your treehouse. This is my treehouse – my solitude.” (audio below)

Dam plans to finish his bachelor’s degree online and maybe pursue postgraduate education. Whatever he does, or wherever he is, he wants to help students. Meanwhile, he is helping his mom with the bills and the paperwork for her nail salon.

#FINDINGAMERICAN

To receive updates on the book release and exhibition of “Finding American: Stories of Immigration from all 50 States” please subscribe here. This project is a labor of love (and passion). If you would like to support the project’s continuation it would be greatly appreciated!

© Photos and text by Colin Boyd Shafer | Edited by Kate Kamo McHugh. Quotes edited for clarity and brevity.