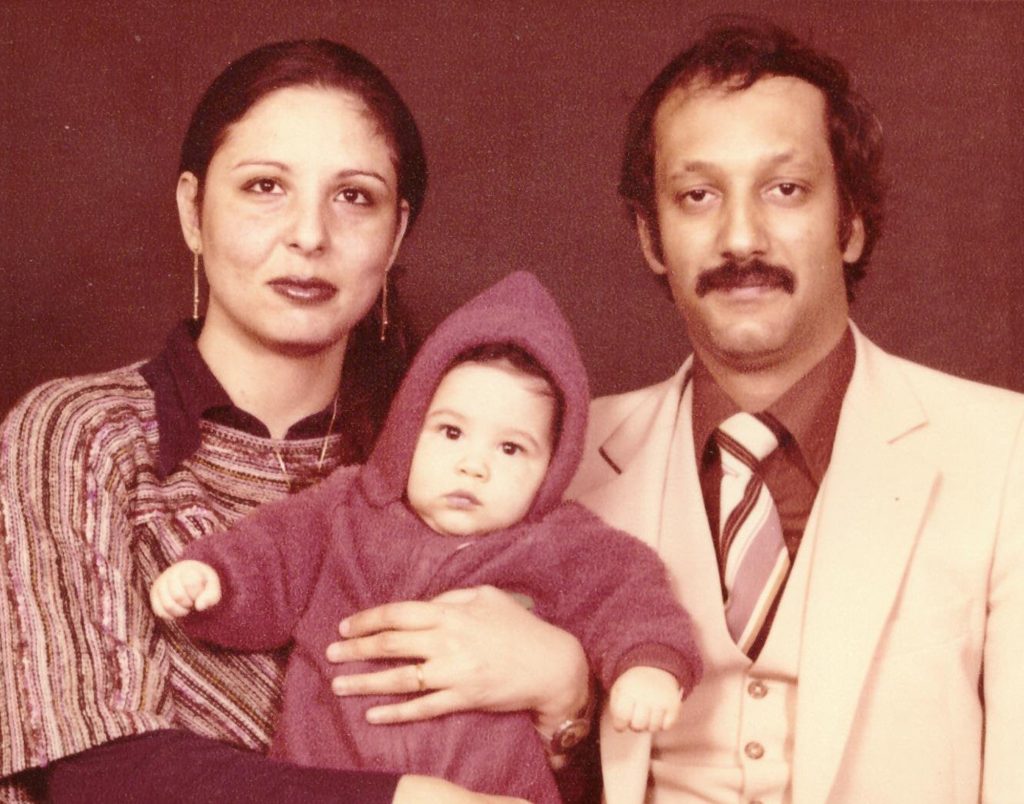

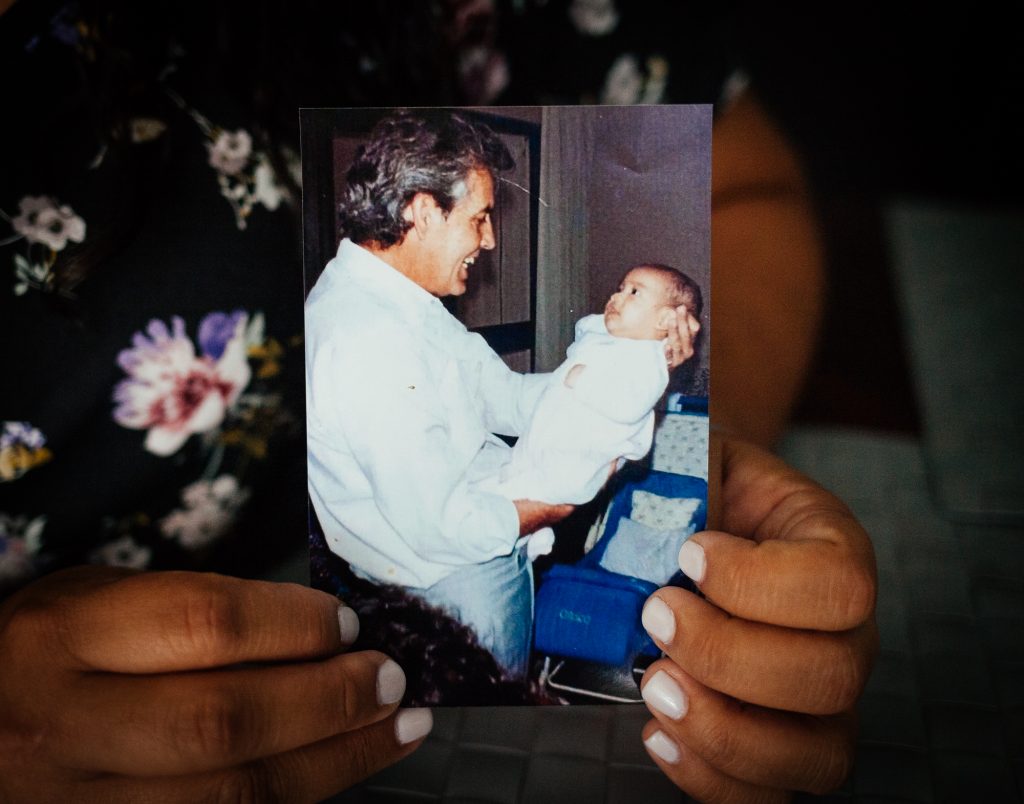

Dhamarys’s father came to the United States in 1981. He had been married before, and his daughter from his previous marriage helped him get a green card. He didn’t like the United States and ended up returning to the Dominican Republic in 1983. Dhamarys’s father has a total of 11 children, and four of them were with his second wife, Dhamarys’s mother.

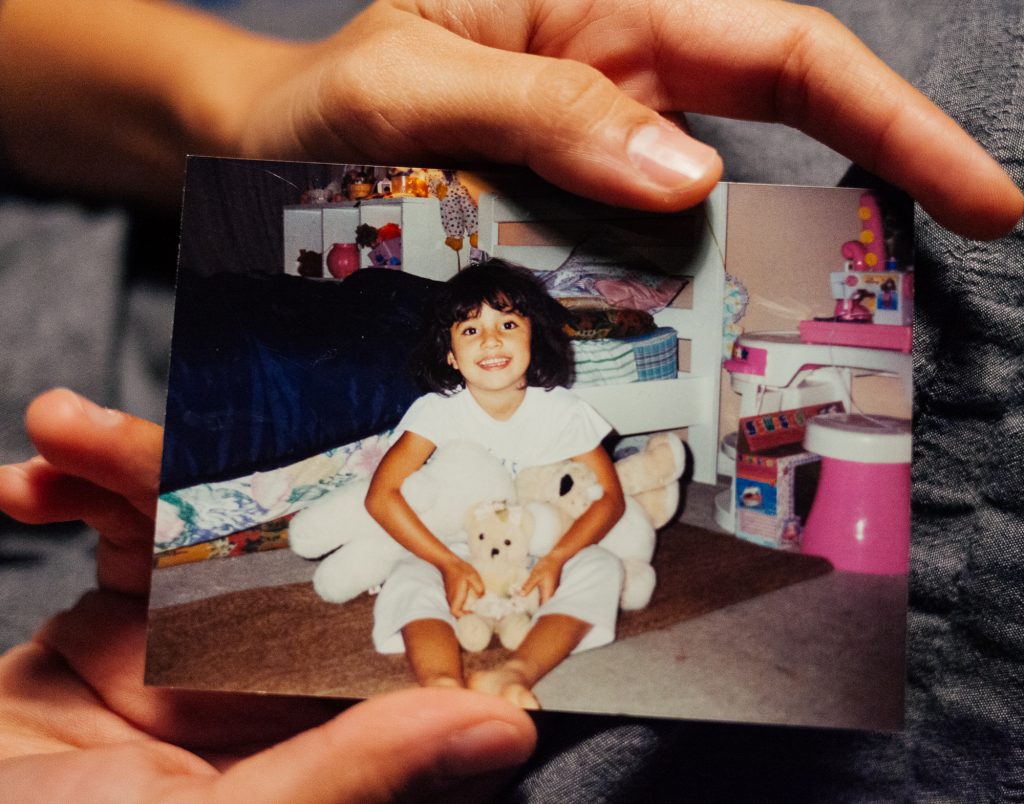

Childhood

Dhamarys was born in Luperon, and when she was three months old, they moved to the capital, Santo Domingo. She had a happy childhood – one where “everybody in the neighborhood was like family.” She remembers how at Christmas time, they would cut the leaves off palm trees to make walls and close the street down to have a giant dance party.

United States

Dhamarys grew up dreaming of going to the United States, specifically New York.

“Everybody wanted to go to New York. It was called New York, not the United States!”

Dhamarys’s father always said he would never return to the US, but eventually, her mom convinced him otherwise and he left for New York City in 1984. He worked nonstop and it took three years before he completed the immigration process for Dhamarys’s mother and their four children. In 1987, when she was 19, Dhamarys, her mother, and her three younger siblings, all moved to the US. It wasn’t an ideal time. She was leaving her dog and a fiancé behind in the Dominican Republic. She was supposed to return for her marriage after three months, but that never happened. (audio below)

When her father was in the US without the rest of the family, he was working at New York City’s Four Seasons Hotel, working as a dishwasher. Before they joined him in the US, he decided that he didn’t want his children to grow up in NYC. Another dishwasher told Dhamarys’s father of a cousin in Rhode Island who could help the family get set up there. Her father trusted this man, so he rented a U-haul, bought a map, and the family headed for Providence, Rhode Island. The dishwasher’s connection had left keys in the apartment mailbox. They arrived and unpacked everything into the one-bedroom apartment. Dhamarys remembers it being so cold.

“We knew we had to stick together to survive.”

Survival

The next day at eight in the morning, someone knocked on their door. It was a tall man who was speaking English rapidly, and the family couldn’t understand what he was saying. He left and came back two hours later with a police officer who spoke Spanish.

“You have 24 hours to leave this apartment.”

Their connection, who said they could stay there, was himself a renter, and the lease was only for a single occupant. The tall man at the door who spoke English was the actual owner. Desperate, they found another apartment in “the worst part of Providence.” The tenants in the first-floor apartments were drug dealers, and their third-floor apartment was undergoing renovations. There was no furniture, no kitchen, and no heat – they had a mattress on the floor, and they managed to get a little space heater. After a few weeks, the renovations finished, and they started getting settled.

Within two weeks of arriving in Rhode Island, Dhamarys, her parents, and 14-year-old brother Raul started working. They would walk three miles every day to work in the same electronics factory assembling computer parts. Dhamarys’s younger siblings: Luisa, ten, and Nathalie, eight, started school. She was amazed at how quickly they picked up English.

“I was jealous as I couldn’t go to school. I just had to work to help my family.”

She will never forget the day her mother asked her to leave the factory at lunch to buy eggs. She tried to ask the man at the supermarket for “huevos”, but he didn’t understand her. Next, she tried making chicken sounds, but he thought she wanted to buy a whole chicken! One of her coworkers happened to have been at the supermarket and overheard everything. Dhamarys finally got the eggs, and by the time she got back, her coworkers at the factory were all laughing and clucking like chickens. (audio below)

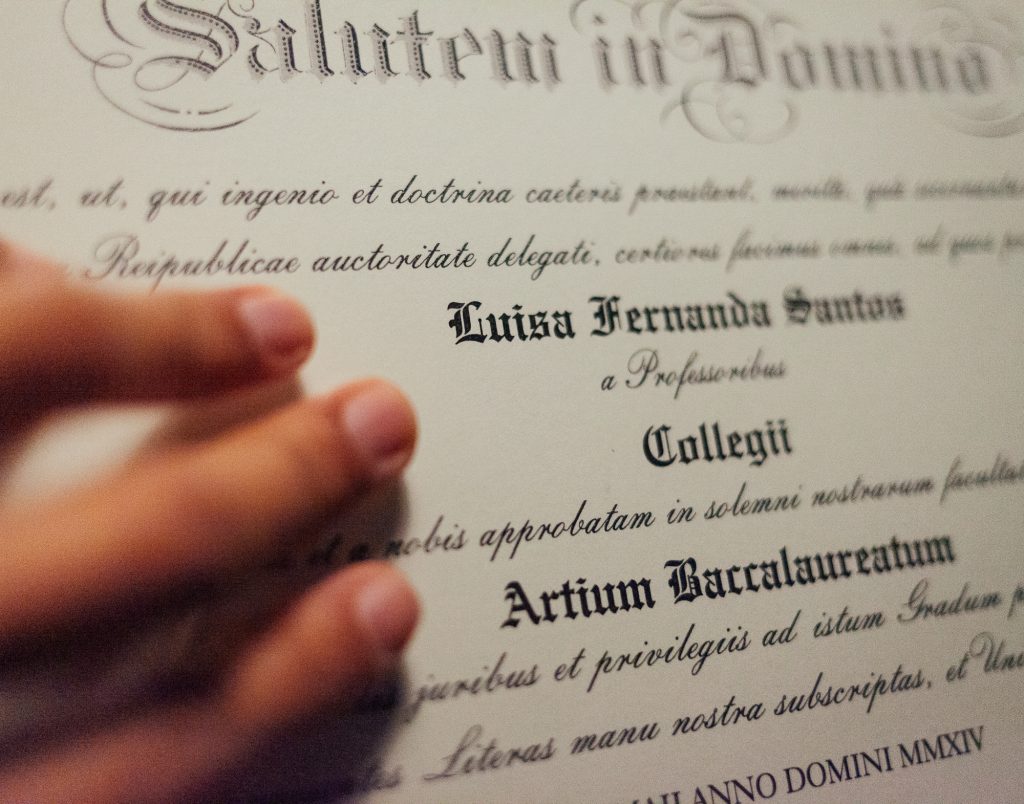

Nursing

Her father never stopped reminding Dhamarys that she needed to go back to school. Eventually, she left the factory, started working at a gas station, and enrolled in classes to become a nursing assistant.

There was one woman who always came to the gas station to buy cigarettes. Dhamarys kept noticing her badge and eventually found out she worked at the Women & Infants Hospital. She told the woman that one day she is going to be a nurse there too. Dhamarys signed up for CNA (certified nurses assistant) classes, passed, and got her license in 1992. She worked first at a nursing home, then applied, and just like she told that woman in the gas station, Dhamarys started working at the hospital in 1994. She felt so proud walking into that same gas station wearing her badge. (audio below)

In 2008 Dhmarys graduated from nursing school with an associate’s degree, and in 2014 she went back to get her Bachelor of Science in Nursing at the University of Rhode Island. Dhamarys couldn’t have done it without the Women & Infants Hospital financially supporting her degree. Dhamarys only took one class at a time because she was working forty-hour weeks, but in 2017 she graduated as a Registered Nurse.

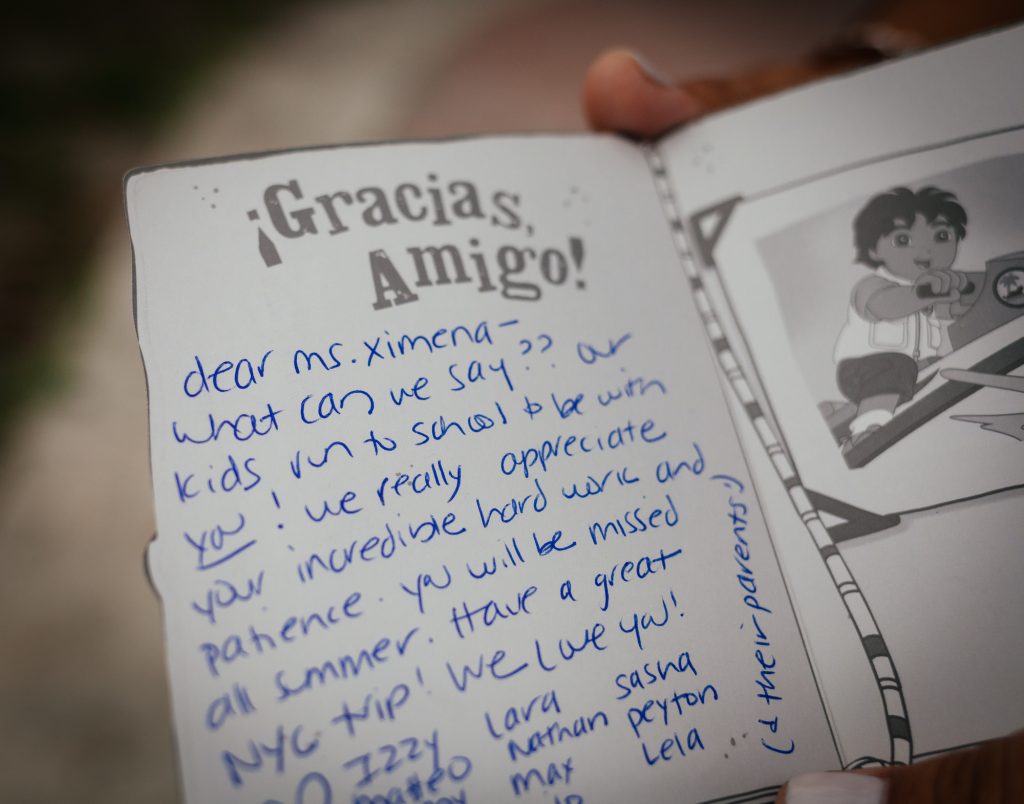

While earning her nursing degree, Dhamarys had the opportunity to substitute a class for a trip to help people in Haiti [see the photo above]. As a nursing student in 2015, she went to remote places to provide free healthcare to communities in need. Dhamarys has continued going to volunteer in the Dominican Republic. Even though now it costs her money to volunteer, she thinks it’s worth it.

“They take you to the poor, poor places, and it is so rewarding. They appreciate it so much. Every year I put signs in the Women & Infants Hospital and collect stuff like medicine. I love to go. It’s very rewarding to give back to your country.”

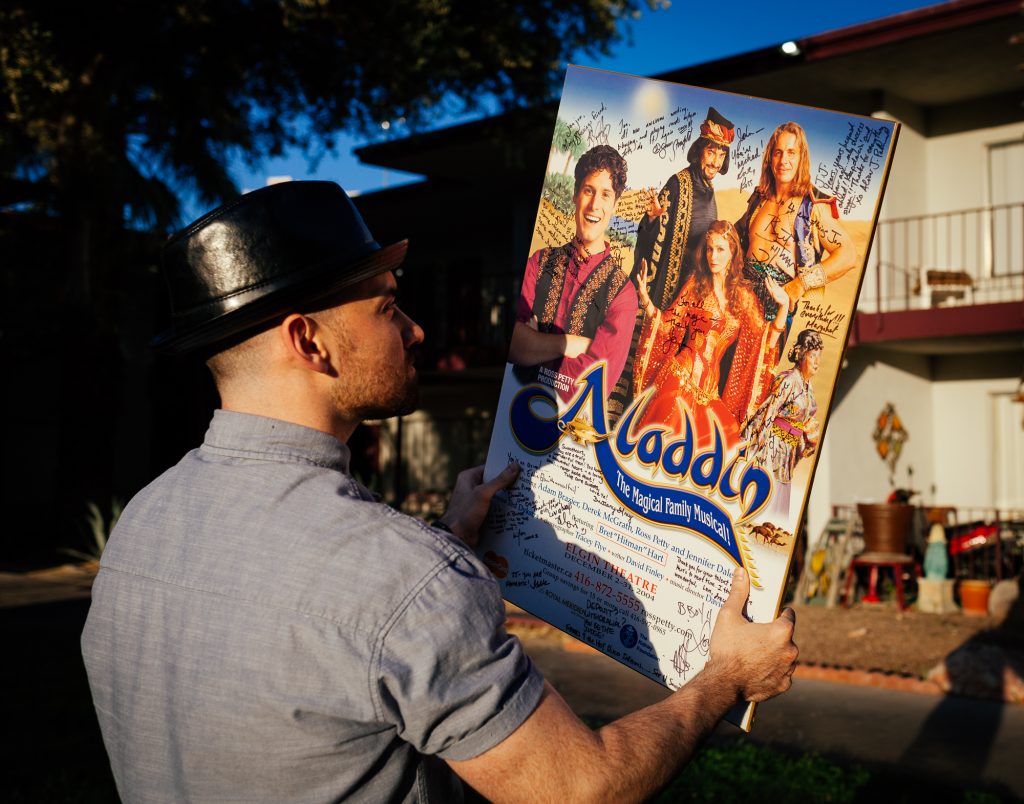

Not only is Dhamarys working as a nurse at the hospital, but in 2017 she picked up a part-time job at the airport. She has always loved to travel, but could never afford it. Now she can fly for free. When she went for the interview, they asked her why she would want a job inspecting food carts, when she is already working as a nurse. Her response was, “Because I want to fly. I’m not gonna lie to you!”

Rhode Island

Dhamarys loves Rhode Island. She loves the people, the beautiful Atlantic Ocean, and the superb seafood.

“It may be the smallest state, but there is a lot to do here. Any culture you can think of, we have it here. I don’t think I will ever move out of Rhode Island.” (audio below)

Most of Dhamarys’s friends in the US are Dominicans. There is a street in Providence called Broad Street that is like a “little Dominican Republic”. According to Dhamarys, it’s where you can find some of the best Dominican food in the United States. She doesn’t follow politics in the DR, but says, “culture-wise I follow the Dominicans.”

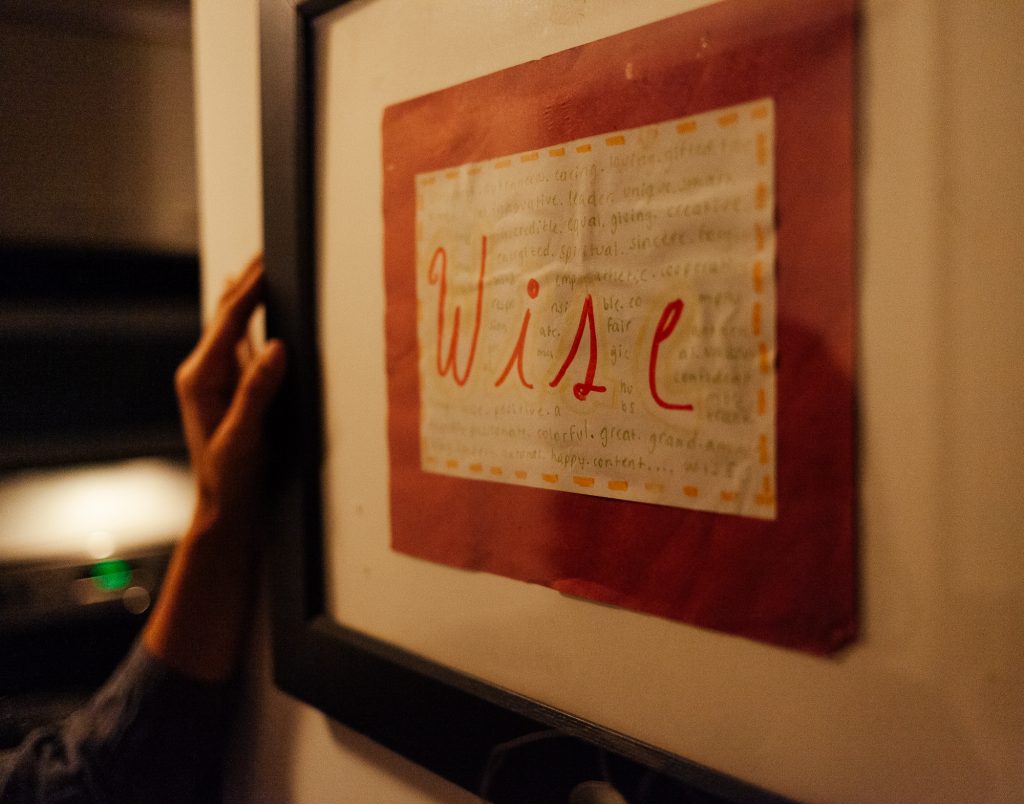

Language

Dhamarys’s language ability and her accent is something she is very conscious of all the time. Studying in English has always been extremely hard for her.

“Something that you can read one time and understand, I have to read five times.”

Dhamarys finds it hard to pronounce many English words and says she appreciates it when people correct her pronunciation. She has never experienced discrimination because of her accent, but it still makes her self-conscious.

“I have a very strong accent. I worry about it all the time. That’s why I don’t like to speak. I always feel very uncomfortable.”

In order to complete her Nursing degree, Dhamarys had to take a communication class and give a presentation. Nothing makes her more nervous than public speaking.

“One of the girls in class says, ‘take an Ativan.’ I said, ‘oh, would that make me calm down?’, and she said ‘yes’ and gave it to me. Let me tell you; my accent wasn’t the problem; the problem was I couldn’t speak!” (audio below)

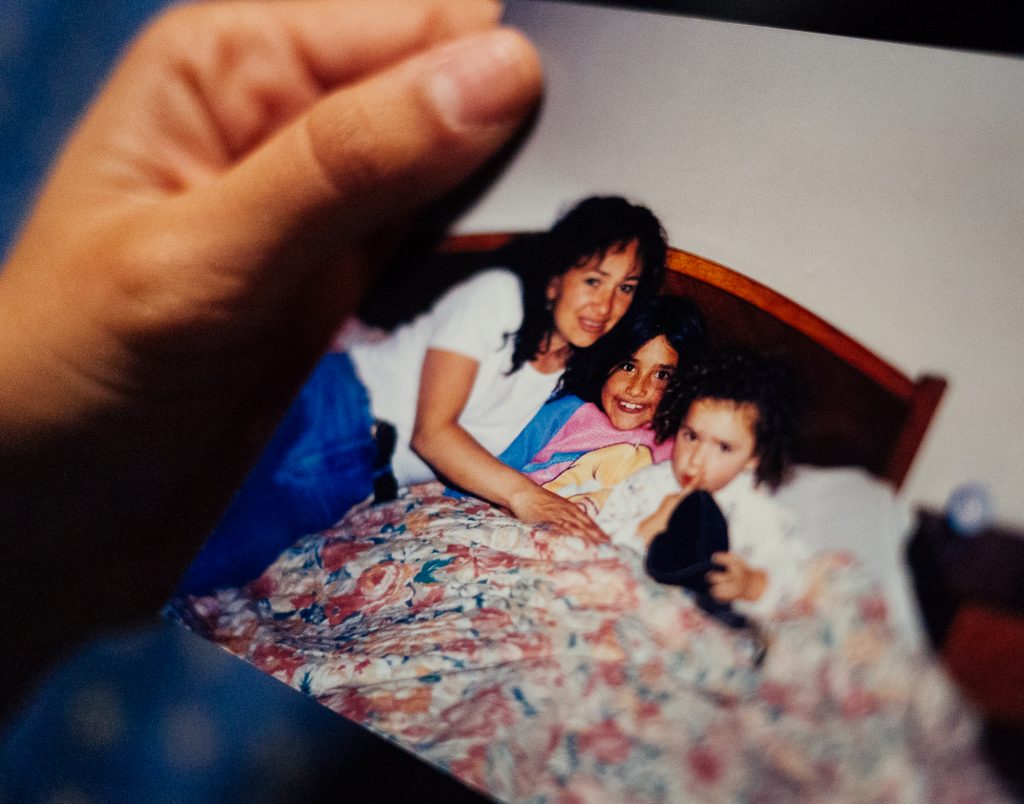

Parenting

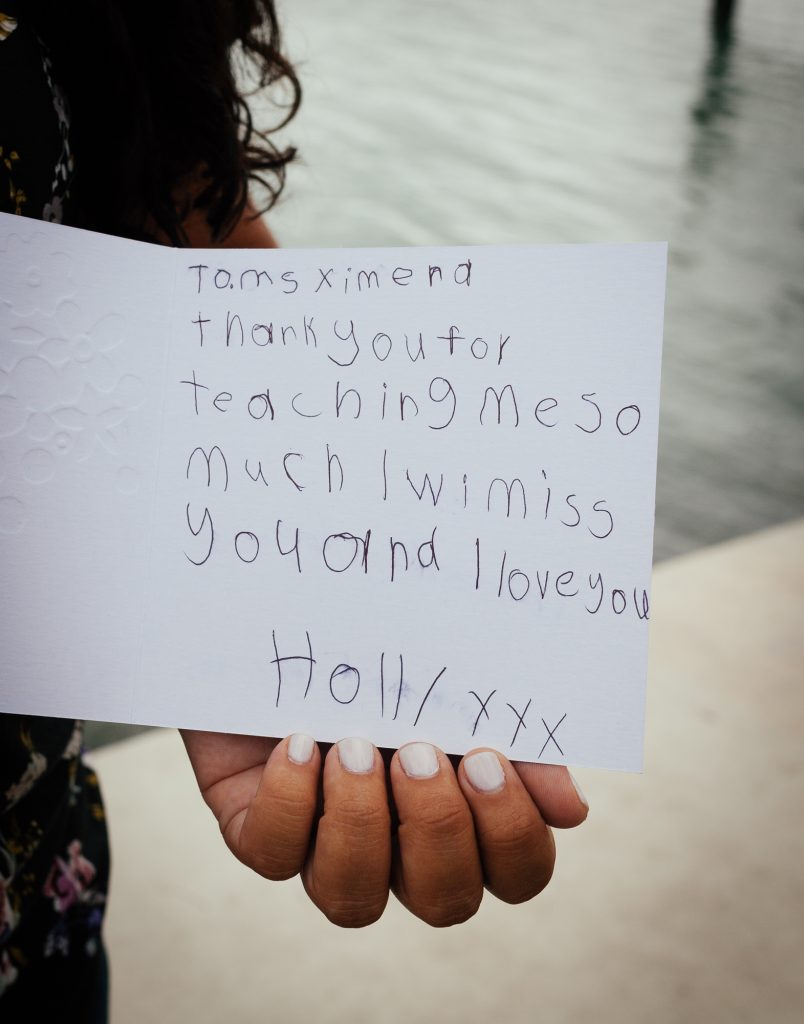

Dhamarys’s entire family lives in the United States now. She has two children. Her son is a sheriff patrol officer in Florida and her daughter just started high school in Rhode Island and hopes to be a nurse anesthesiologist.

When Dhamarys’s son comes home to visit, they go out to the club together with all of his friends.

“My son always says, ‘my friends are asking for you,’ and I say, ‘That’s because I’m young, baby!’” (audio below)

Dhamarys has her daughter every other week. When she does, her parents pick her up from school each day, then Dhamarys joins them after work for dinner. Dhamarys jokes that the kitchen in her house “is just for decoration.” Dhamarys tries to include her parents in everything she does. She recently took them on a surprise cruise and they all had a blast.

“My parents are so good to me. I am the oldest, and I feel like I am the favorite.”

When she has free time on the weekends, Dhamarys loves to dance the Bachata. (audio below)

Future

Dhamarys’ dream is to retire at 59 and travel. The only problem with this plan is that she loves her job at the hospital, so she’s not sure how she could give it up. No matter what happens in the future, Dhamarys continues to have a joy for life that is infectious.

“I try to be positive. Everything is difficult in life, but if you have a negative mind, it is more difficult. I feel that people are more willing to help you if you don’t complain about things. It has worked for me.” (audio below)

*Update: Since the interview, Dhamarys started selling real estate, and in 2019 she was awarded the “Hospital Hero” at Women and Infants Hospital.

#FINDINGAMERICAN

To receive updates on the book release and exhibition of “Finding American: Stories of Immigration from all 50 States” please subscribe here. This project is a labor of love and passion. If you would like to support its continuation, it would be greatly appreciated!

© Photos and text by Colin Boyd Shafer | Edited by Kate Kamo McHugh. Quotes have been edited for clarity and brevity.