Childhood

“You hear all these stories of Roma – commonly but problematically called ‘gypsies’- moving, traveling, wearing colorful clothes, having long hair, and other romantic fantasies about the ‘gypsy’ lifestyle. Thinking about my childhood, it could not be farther from the truth.” (audio below)

Cristiana was born in Slatina, a small town where there wasn’t much for a child to do. There was one main factory in town that produced aluminum that employed her father his entire working life. This factory was their family’s financial security and stability. Whenever you drove into the town, you would see a dark cloud of smoke coming from the factory. Reflecting on the pollution, it doesn’t surprise Cristiana that as a child, she always had problems with her lungs.

Cristiana’s mom married her father when she was 16. They met riding the bus that went to the town’s only cinema. Mistakenly she thought she knew him, so she started talking to him. He played along. Eventually, she realized he wasn’t who she thought he was, but by that point, she actually was starting to like him. Cristiana’s mother still jokes with her husband – “You are not the man you said you were!”

Cristiana’s mother’s childhood was short. On her way home from her very first day of school, she was in a horrible car accident. After recovering from being in a coma, she returned to school at the insistence of a teacher who believed in her potential. The teacher had the best intentions – to get an intelligent and curious child back on track – but her classmates were already too far ahead. Then when she was a teenager, her mother (Cristiana’s grandmother) was sick with cancer, so there was no chance for her to fully focus on her education or career. After growing up with such complex challenges, she wanted Cristiana and her brother to have a playful and carefree childhood with access to the best education, something she dreamed of but never had.

Grandparents

Cristiana’s paternal grandparents’ village, Balteni, was two train stops away. Traditionally, the youngest son (Cristiana’s father) stays in the village and takes care of his parents. Cristiana’s mother challenged this norm and insisted her family live in Slatina so that Cristiana could go to school. Every weekend or holiday, they would visit her grandparents as a compromise.

Cristiana remembers one spring she went to pick flowers with her grandma. They found snowdrops growing, removed them with the roots, and replanted them in grandma’s garden. The following spring, the flowers emerged from under the snow and just kept growing. Cristiana’s parents live on the property now, and she always asks them how her snowdrops are doing. Recently, Cristiana’s mother pressed a few and sent them to her by mail [see the photo above]. (audio below)

Cristiana’s grandparents were very active in their community. Despite the “invisible wall” that existed between Roma and non-Roma in their village, they were at the highest place a Roma could be in the local societal hierarchy – somewhere between tolerated and respected. Her grandfather was a respected blacksmith. His non-Roma neighbors would happily work with him, but they wouldn’t want any of their children to marry any of his children. The land he owned and the houses he built made Cristiana’s grandfather proud- a pride she couldn’t understand as a child. He would always say, “I bought the corner of the village.” As a kid, Cristiana would roll her eyes and say, “oh, grandpa is talking again about all the things he’s accomplished.”

“When I came to terms with my Roma identity, I started to see how Roma live life and the instability they have and how transient some of their lives are. I started to understand why my grandfather was so proud. For him, space, land, and belonging were incredibly important. I took that for granted as a kid.” (audio below)

Priviledged & Roma

“On one hand, I had a story of being Roma – working-class on the edge of society – and yet my story is one of incredible privilege and support from family.” (audio below)

Cristiana feels like she grew up very privileged in an underprivileged family. Her parents worked so hard and had little money, yet they never asked Cristiana for any help – they only wanted her to focus on her studies. She didn’t even have to do many of the chores other kids her age were doing, like taking out the garbage or washing the dishes. In high school, her parents spent the majority of their incomes (and even took out a loan), so Cristiana could be privately tutored. They didn’t want the limitations of their class to affect their daughter’s chance for success.

Cristiana’s mom worked as a cleaner near Cristiana’s school so she could be close to Cristiana and her younger brother – dropping them off, picking them up, cooking for them. She did this throughout Cristiana’s schooling. Cristiana remembers how that embarrassed her at the time – that her mother didn’t have a “profession,” her classmates’ mothers. When she looks back now, she feels so proud of her mother.

“She was this gorgeous young woman who didn’t care about how it looked on the outside. She found a pragmatic way to make sure we went to good schools and financially contributed to the family.” (audio below)

Her father has a darker complexion and looks more Roma. To protect her identity, only Cristiana’s mother picked her up from school. (audio below)

“I heard stories of her going to the hair salon, with me along, and the ladies there said, ‘Your daughter is so beautifully suntanned. How long did you spend at the seaside?’ They couldn’t imagine that we were Roma.”

Hidden Identity

Cristiana didn’t have many friends growing up, primarily because she didn’t want her classmates to know she was Roma. She never invited anyone home to play in her small apartment.

“You learn how to keep a family secret in order to fit in. I did fear that I would treated badly as a Roma, but I found coping mechanisms – never inviting kids home and separating my school life from my family life. As a kid, you want to fit in, and you do everything you can to be accepted by others. Looking back, it is just so heartbreaking.” (audio below)

Hiding her true identity was challenging, but it allowed Cristiana to go to school without facing daily discrimination. It was an isolated existence but she wasn’t the type of person to get bored. She had a great imagination and spent a lot of time reading stories and dreaming.

She figures that by high school, her two best friends had figured it out. They saw how she never invited them over, and they had the wisdom not to ask questions. Instead, they would invite her to their homes.

“I never saw Roma women on television who are considered smart and confident and beautiful – who are acknowledged for who they are and their skin color is not a problem, so I always hoped nobody would notice it.” (audio below)

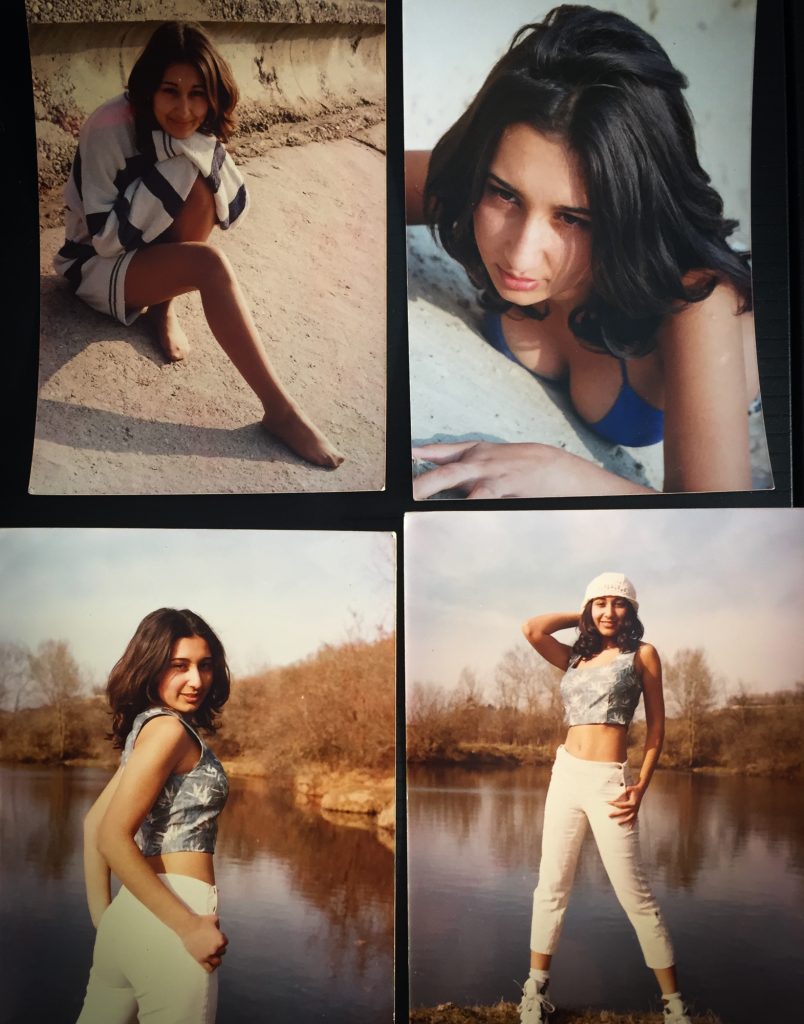

Cristiana’s parents always made sure her hair was short [see the above photo], so society wouldn’t think she was Roma. Her mother dressed her in greys and browns, never anything colorful. Her mother wanted her to look as far as possible from “the stereotype of a flashy gypsy with shiny clothes and long hair.” Cristiana hated her hair being so short. She remembers a doctor joking with her once, how if she didn’t have earrings on, he would have thought she was a boy.

“I was this dark skinny kid with very short hair. Being beautiful was the last thing that crossed my mind. I was just hoping nobody would hold it against me that I was ugly. Nothing about me was girlish. It was hard.” (audio below)

Discrimination

Despite doing her best to hide her true identity to avoid discrimination, it did happen. She only remembers a couple of instances. At the end of first grade, she received an award for having the best grades in the class.

“After the celebration, one of my classmates’ parents went to my teacher and said, ‘how can you give the best award to a gypsy girl?’ The teacher said she deserved it – she had the best grades. It was the last time I had the best.” (audio below)

After this, Cristiana always made sure never to be the best. “It was a trade-off – a compromise between being accepted and excelling.” Now, these memories enrage her.

Confidence

By the sixth grade, Cristiana started to grow her hair longer with bangs, and a few classmates commented that she looked like Cleopatra.

“It was the first time that I felt powerful and beautiful.”

When she was 15, a photographer in her town approached her and asked if he could photograph her – telling her she would look beautiful in his photos. She looked at some of the other models he had shot and couldn’t understand why he wanted to photograph her. She thought it was a joke.

“When I saw the first photos printed, I didn’t recognize myself. That was the beginning of me feeling more confident and seeing myself in a new light. “

In retrospect, Cristiana is happy she didn’t spend her youth worrying about clothes or hair. It allowed her to focus on other “more substantial profound things.”

“I feel comfortable with this ugly duckling story.”

United States

Cristiana’s first trip to the US was in 2006 at the end of her third year of college as part of a summer student program. She was 22, it was her first time abroad, and she was going to work at a fancy country club in Maryland. She admits it sounds cheesy, but “it was like a script from a Hollywood movie. I had the right people at the right moments, who were open and receptive and kind. I was like Alice in Wonderland”.

The country club decided they had too many summer students, and Cristiana needed another job. Luckily, Steve, this Italian American manager at a restaurant in Baltimore, came to her rescue. He found her a friend’s empty house to live in, two part-time jobs, and he even invited her to an Italian wedding.

“It made me feel like I belong in a way I had never felt before. The support and care and kindness I met in the US gave me the energy and strength and inspiration to go through the process.”

This overwhelmingly positive experience in Maryland gave her confidence to explore her identity as a Roma.

“It was eye-opening, and at the end of that summer, forced by circumstances, I talked about my Roma identity for the first time. The beginning of this journey of trying to understand for me what it means to be Roma, understand the Roma people and see where I fit in. It’s hard redefining who you are and exploring a part of your life you avoided for so long.”

Cristiana returned to Romania, opened her computer, and started researching – “who are the ‘gypsy’ people”?

Cristiana felt inspired like never before to make a difference in Romania and the world. While finishing her psychology degree, she started an organization to help youth employability and soft skills. Still, the focus wasn’t explicitly on the Roma; it was a mainstream initiative for Romania.

As she contemplated her next steps academically, she had to continually fight with her grandfather’s voice in her head – “Have you ever seen a gypsy who was a teacher or a lawyer or a professor?” (audio below)

Academia

Cristiana wasn’t going to let stereotypes stop her. In 2009, she received a Fulbright scholarship and went on to earn a Master of Education Policy at Vanderbilt University. It was a real immersive liberal arts experience – writing articles in the newspaper, taking electives in film studies, and she even started taking ballet.

“Ballet has been the most incredible discovery for me on a personal level. I used to say I hope my future children will not deal with the challenges I dealt with, and they will do ballet. There was a moment at 26 when I realized I was talking about myself. It permitted me to do the thing I only dreamed of as a child.”

Her professors at Vanderbilt were encouraging when it came to her exploring her Roma identity.

“Being Roma went from being a complete secret to being a big part of my life. Once I take responsibility for something, I am a car without a brake.”

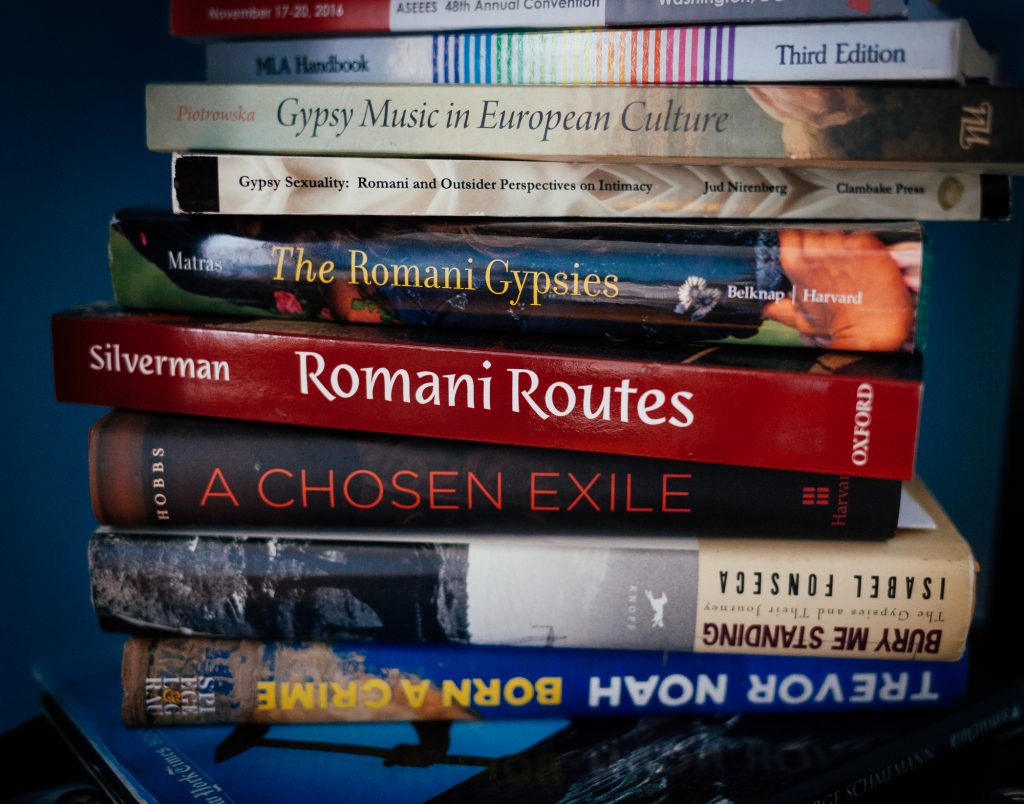

Cristiana wanted to add research to what she already knew through lived experience as a person from the Roma community. The more she researched, the more she realized there aren’t many books about her community. There also aren’t many Roma who have had the academic experiences she has had, and some Roma who are academics aren’t “public” about being Roma. Cristiana believes that “being vocal about being Roma is exceptional,” and she hopes this changes.

Roma Peoples Project

After graduating from Vanderbilt, Columbia University accepted Cristiana to continue her research on the Roma. She saw how researching the Roma could shed light on the experiences of other minority groups.

“It is a time right now in the US and world where more and more minority groups are coming to terms with who they are and struggling to understand their place in the world.”

Columbia has had Roma students, but they’ve never had a project on Roma issues. In 2017, Cristiana launched the Roma Peoples Project, which operates under the Centre for Justice. The project aims to start a dialogue at Columbia and in society at large about the Roma people.

“It was my personal search and desire to understand a complex identity that is not yet explored or understood. I want to do this work because I know how fortunate I have been.”

The project involves collecting materials on the Roma and creating a centralized digital archive, as well as highlighting the stories of people who are Roma.

“People are amazed that there are 12 million people who are Roma, and we know so little about them in academia. Then there are other people who know about the Roma but have never had a space to share these stories.” (audio below)

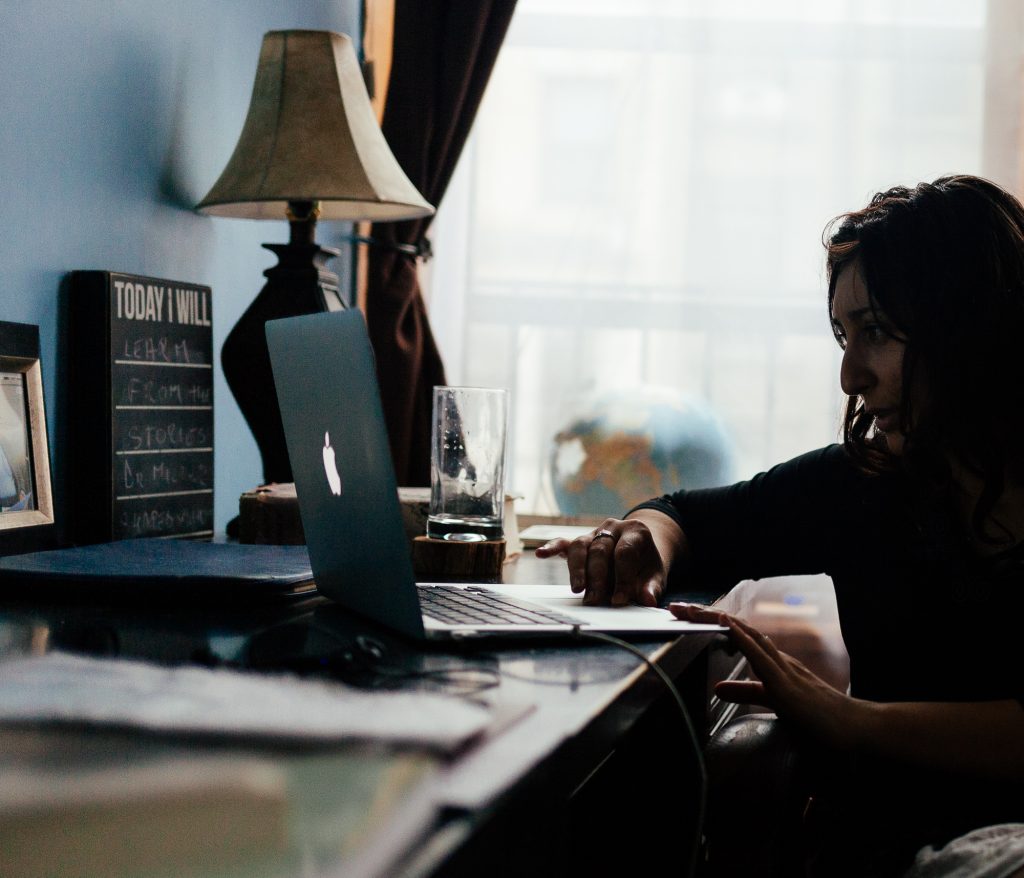

In her work, Cristiana discovered that a lecturer at Columbia, Dana Neacsu [see the photo above], created one of the first annotated bibliographies on the Roma people.

“I keep discovering people interested in the subject who already worked on this topic, but there hasn’t been a space to bring us all together.”

Cristiana still dreams of Romania. Every summer, her grandparents cultivated potatoes, and other vegetables. She loved it when they asked her to go out look for them – like a treasure hunt. In NYC, Cristiana lives close to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and regularly walks around the great lawn to look at the various objects. Once, she had a dream that brought these two very different places together.

“I was in their village in the potato garden, but instead of finding potatoes, I was finding art objects from the Metropolitan Museum of Art! What does this mean? The way I interpret it is that these two worlds have mixed. Maybe the next dream will be about finding potatoes instead of art objects here?” (audio below)

Hopes & Dreams

Cristiana hopes her project will create a space for Roma to express themselves that is not tied to geographical location, especially since the Roma people are so dispersed.

“We are a global people by definition. We have a multicultural identity, and live in so many parts of the world – mobility and a more fluid relationship with cultures are at the core of how this identity has been shaped for centuries. I hope that we will understand that there is a diversity of ways that you experience this Roma identity. That’s the beauty of it. What it means for me to be Roma is different than what it means for others.”

She wants to inspire other Roma, who may be struggling with their identity, to become more vocal about it. Together, they can redefine what it means to be Roma.

“There are many incredibly successful and talented people who are Roma, and by speaking with their customers, students, and friends about being Roma, they could shatter stereotypes.”

Cristiana hopes that other universities will create projects and institutes associated with Roma Studies, not just for the sake of the Roma community, but as a way of understanding marginalization, displacement, and migration in general.

“The Roma have been permanent refugees in Europe for over a thousand years. If we can understand the condition of Roma, and people who have survived without a country for so long, we can understand the modern condition. To deal better with a world that is faced with more displaced people and refugees. There is a richness of information that can be explored beyond ways in which it can contribute to Roma people.” (audio below)

Cristiana is working hard so a new generation of Roma will grow up confident, with a strong sense of who they are and with role models who have a variety of professions.

#FINDINGAMERICAN

To receive updates on the book release and exhibition of “Finding American: Stories of Immigration from all 50 States” please subscribe here. This project is a labor of love and passion. If you would like to support its continuation, it would be greatly appreciated!

© Photos and text by Colin Boyd Shafer | Edited by Kate Kamo McHugh. Quotes have been edited for clarity and brevity.