Childhood

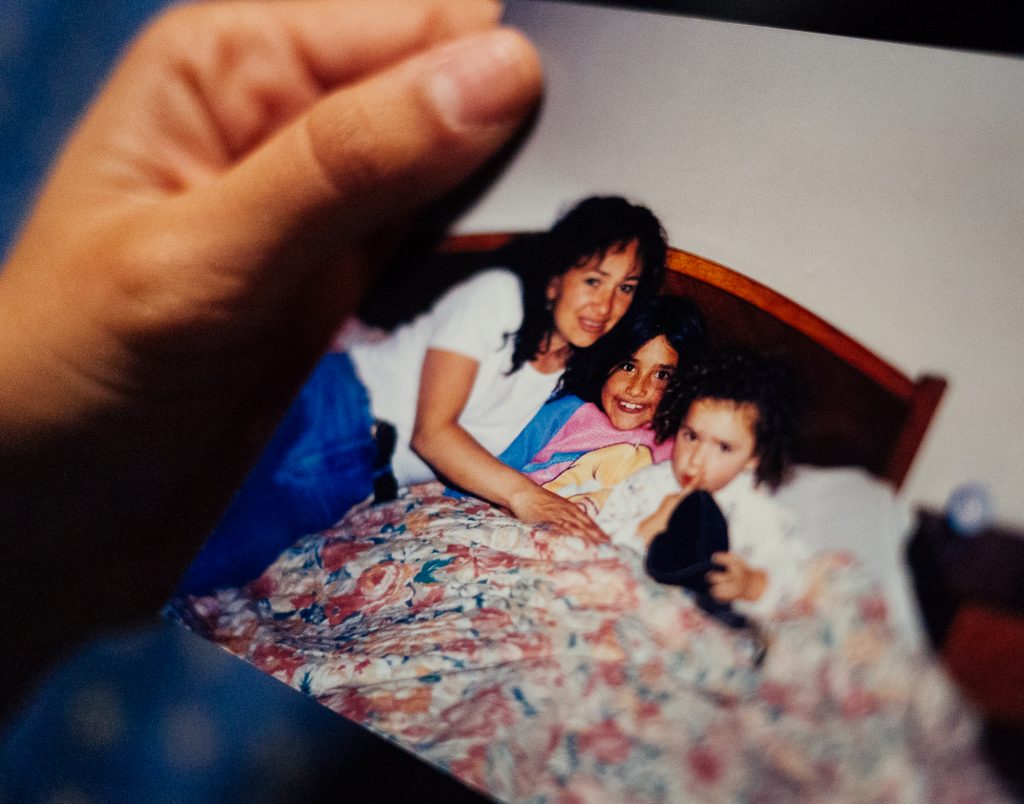

Luisa lived in Bogotá until she was eight years old. Her early life consisted of playing outside with the kids from the block and spending time with family. Luisa’s mother taught technical drawing at the university, and her father worked for Coca Cola, opening new plants all around Colombia.

Trip to Disney World

At the time of her parent’s marital separation, her maternal grandmother, as well as aunts and uncles, were already in the US. In 1998 Luisa’s mom took Luisa, age eight and her younger sister, on a trip to Disney World. They never returned to Colombia.

“My mom was convinced by her family to stay. We came to Florida with one suitcase and stayed after our vacation.”

Luisa has a clear memory of getting off the plane in Orlando, and everything is bigger, fancier, and more luxurious than she had previously experienced.

“My aunt came to pick us up in an old minivan, and in my head, I was like ‘wow she is so rich, and this car is so big and beautiful.’”

Adjusting

Immediately after they arrived, Luisa’s mom, the former university professor, started cleaning homes – just like her aunt and grandmother did when they came to the US. They brought Luisa’s mom along with them to introduce her to the people whose houses they were cleaning, and she started cleaning three homes a day. Luisa’s father wanted to reconcile with his wife, so he came to the US on a tourist visa and ended up staying with them. He learned the basics of being a handyman and starting working as a handyman in America.

Adjusting to life in the US wasn’t easy for Luisa. Other children made fun of Luisa for not speaking English, so she learned fast. Luisa remembers sitting in class doing math equations. While she knew the answer to the problem on the blackboard, she didn’t raise her hand as she didn’t know how to say the answer in English. Trying to communicate with her limited English was not worth the risk of her peers making fun of her. She did, however, feel “so important” when her class wrote letters to Bill Clinton, the president of the United States. (audio below)

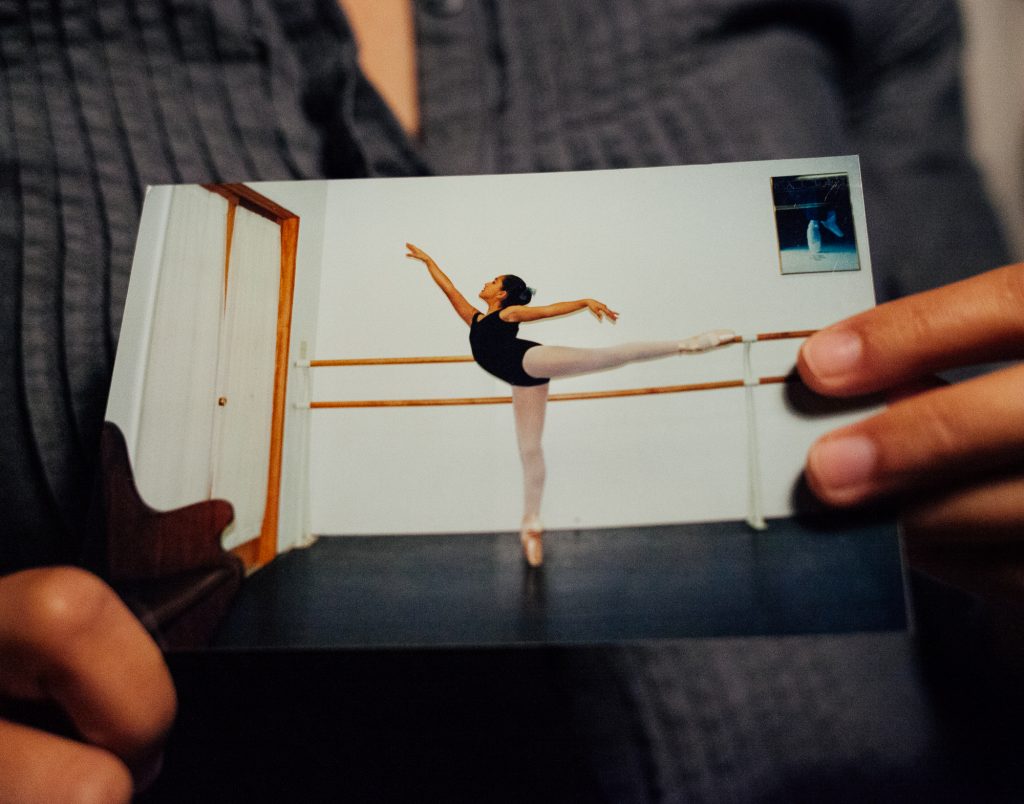

Luisa has had many ambitions, like ballet, but her first career ambition was unique.

“On third grade career day, I told my mom that I wanted to go to school as a tourist. She didn’t break it down to me that that’s not a career. She played along with it and dressed me up with a hat and a camera around my neck.” (audio below)

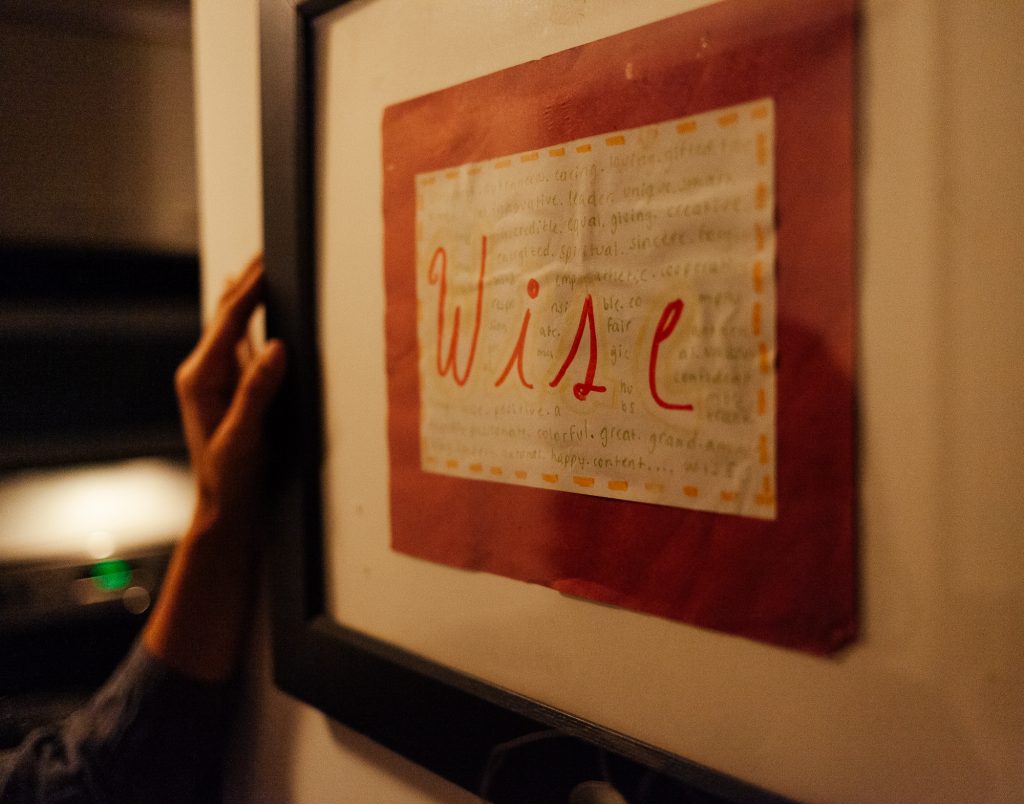

In fifth grade arts and crafts class, Luisa wrote down a collection of adjectives that she wanted to embody, and today it still hangs in her home.

“At the time what I chose to be the big center word was ‘wise’. For a lot of years, I had it taped on my ceiling above my bed. It is actually now so much more meaningful. Now it is a reminder when I come in every day – this is what I want to be, whether I am a business owner, an educator, a sister or a mother. That’s who I am, and I’ve known it since fifth grade without really realizing it.” (audio below)

Undocumented

Before high school, Luisa had never considered that she might be undocumented. When she tried to volunteer, the application asked for her Social Security Number so she asked her parents for it. They told her she didn’t have one.

“My initial reaction was like: ‘Great! Where do I go to get my social security number? Let’s fill that application out!’”

Luisa found out that there was no application or quick solution, and this prevented her from volunteering and from getting an afterschool job. To get to work required that she drives, but because she was undocumented, she couldn’t apply for a driver’s license.

“I felt like I am trying to do all the right things that I’m told I should be doing, and there is this thing keeping me from it that is completely out of my control. It took away my agency, and I felt like my hands were tied. I could no longer control my destiny.” (audio below)

College

Throughout high school, Luisa maintained a 4.0 GPA and was class president. She was the type of student who would typically be going to an Ivy League college. That’s what Luisa intended to do; however, when she found out she would have to apply as an international student due to her status, she was devastated and scared. Luisa feared the colleges reporting her to the authorities (which she realizes was unfounded).

“I felt like I was doing something wrong – living in the shadows – not knowing what to tell who and when.”

If she applied as an international student, she would need to show bank statements proving that her family could pay full tuition – which her family could not demonstrate. She explains how her senior year was particularly tough because she was working towards a life that was not an option. Some schools have gotten better at procedures for undocumented students, but at the time, there was no clear answer. (audio below)

Luisa ended up at Miami Dade Community College, where she had to pay out of state tuition. At least she was going to college and one she could afford. “It took me a while to be proud of the fact that I was starting somewhere.” She didn’t let her status stop her from becoming student body president.

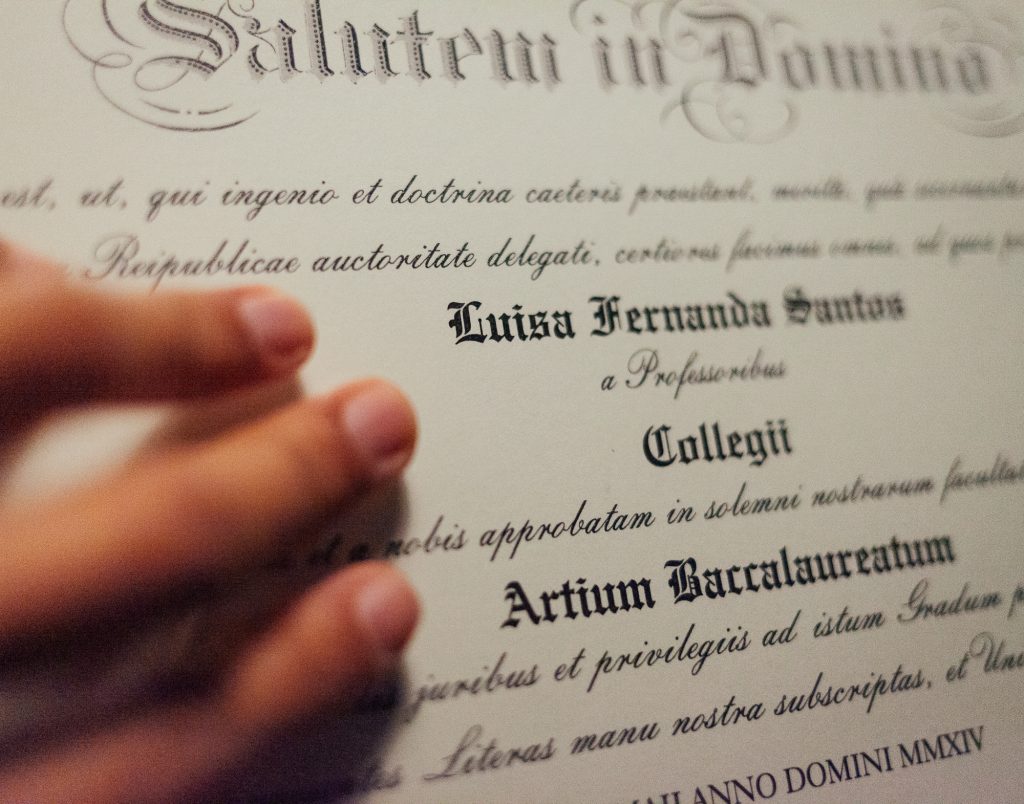

Luisa’s grandmother – a US citizen – petitioned for Luisa’s mother’s citizenship. She waited 15 years for that petition to be processed. In Luisa’s second year of college, her mother’s file was open for review, and Luisa was finally able to become a permanent resident. She went on to attend Georgetown, where she completed a degree in Political Economy, Education & Justice, and in 2015 she became a citizen.

Ice Cream

Ice cream has always been a part of Luisa’s life. She remembers her father picking her up after dance class and taking her to get a frozen treat. In her senior year in college, Luisa’s sister told her about people using liquid nitrogen to make ice cream. Luisa started exploring YouTube on how to do it, and she eventually convinced a liquid nitrogen company to sell to her. The company may have believed that they were selling to the university and not to Luisa for her personal use. Luisa served her first batch to 150 students out of her dorm room. From this experience, she saw how this endeavor could become a business.

At the time, Luisa had been applying to banking and consulting positions. When she finally landed a job, they withdrew the offer because she couldn’t get a security clearance as she wasn’t a citizen. Stuck, the idea of creating her own business seemed more appropriate than ever. In 2015, Luisa opened Lulu’s Nitrogen Ice Cream.

Luisa’s mom now works in the kitchen, and together they have developed some unique flavors like Guava Goat Cheese. Growing up in the desert, Luisa loved cheese and guava paste bocadillos. She brought this memory to life by sourcing local guavas and boiling them for nine hours into the topping for the goat cheese ice cream.

Businesswoman

In highschool, Luisa was in the business academy, as well as developing an interest in international relations and non-profit work. Luisa says she didn’t know what she was getting into when opening Lulu’s. Starting a business was an extremely challenging financial decision. Even though Lulu’s is a successful business, there are many months she can’t pay herself.

Luisa grew up to believe that business people are not the nicest. She is trying to be a different kind of business person – putting ethics before profit.

“There has got to be a way to run a business, make money, and be a nice kind person that also cares about other things.” (audio below)

Luisa is intentional in the way she gives her team feedback. She wanted this business to have a positive impact on the surrounding community – and they do sponsor and donate ice cream to causes Luisa believes in.

One of her favorite professors at Georgetown was Mike Ryan, who taught personal finance. He taught her how money is an opportunity, and what matters is how you use that opportunity. This memory sparked in Luisa the desire to start a program at Lulu’s, which teaches her young employees, most of whom are high school students, financial literacy.

“I know in our current education system, we don’t have financial literacy as a staple, and if you don’t get it at home, you are screwed. This is one thing I can do that could change their lives. We have financial experts come in and teach them the basics. The way you manage can help set you up for future success.” (audio below)

Luisa wants to inspire young women to dream about one day opening their own businesses. A lot of young women visit her shop because they read about her story. Luisa always makes sure that they leave knowing that they can do it, whatever it is that they dream of creating. (audio below)

The Colombian community is strong in Miami, but Luisa isn’t particularly involved in it. She’s been back several times to Colombia, but still, she identifies primarily as American.

“I truly identify as American. I love a lot of things about the United States – it’s my identity now.”

Future

In the long-run, Luisa wants to effect positive change in Florida’s education system. In regards to Lulu’s, she’s not sure she wants it to grow anymore saying, “I am really happy with the way it is today and what it does for the team members and our community.” Luisa is personally invested in Miami and thinks it is an exciting place to be right now. She sees so much potential. Even though she may split her time between other locations in the future, she says,

“I will forever call Miami home.”

*Update: Since the interview, Luisa joined the board of a parent advocacy organization. After attending school board meetings for two years, she decided to run to represent her home district on the school board. Luisa reflects, “Our schools opened many doors for me, and I’m running to ensure that our 350,000 students have the same opportunity to realize their full potential.” You can visit Luisa’s website here.

#FINDINGAMERICAN

To receive updates on the book release and exhibition of “Finding American: Stories of Immigration from all 50 States” please subscribe here. This project is a labor of love and passion. If you would like to support its continuation, it would be greatly appreciated!

© Photos and text by Colin Boyd Shafer | Edited by Kate Kamo McHugh. Quotes are edited for clarity and brevity.