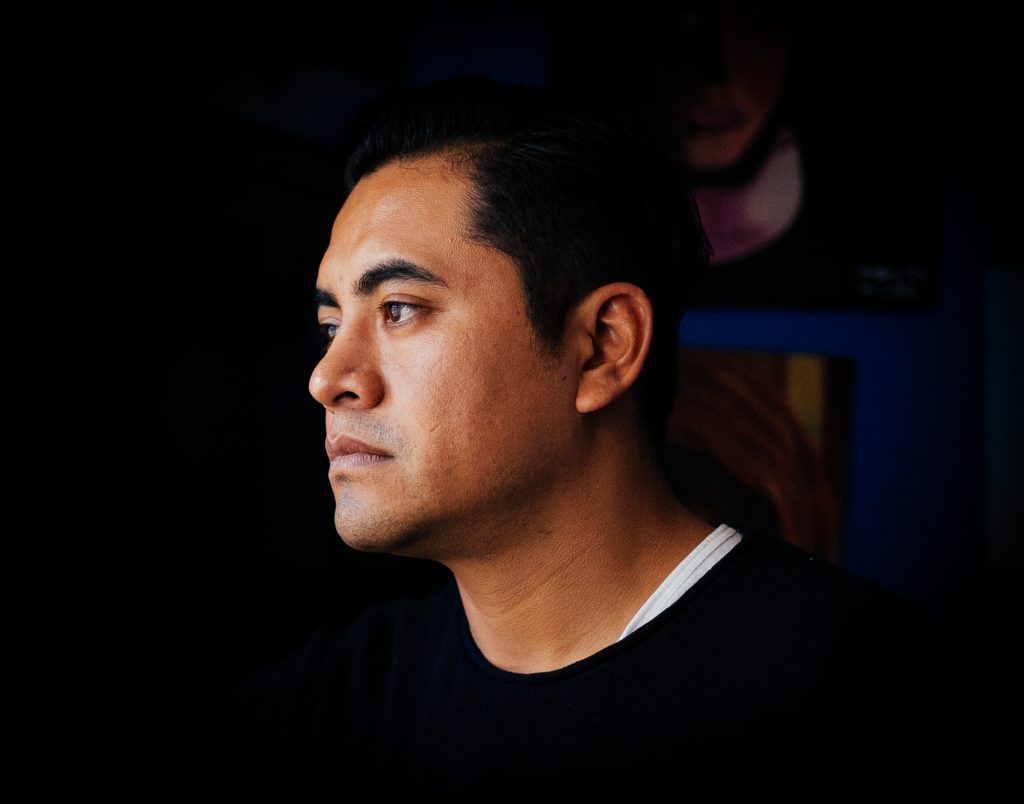

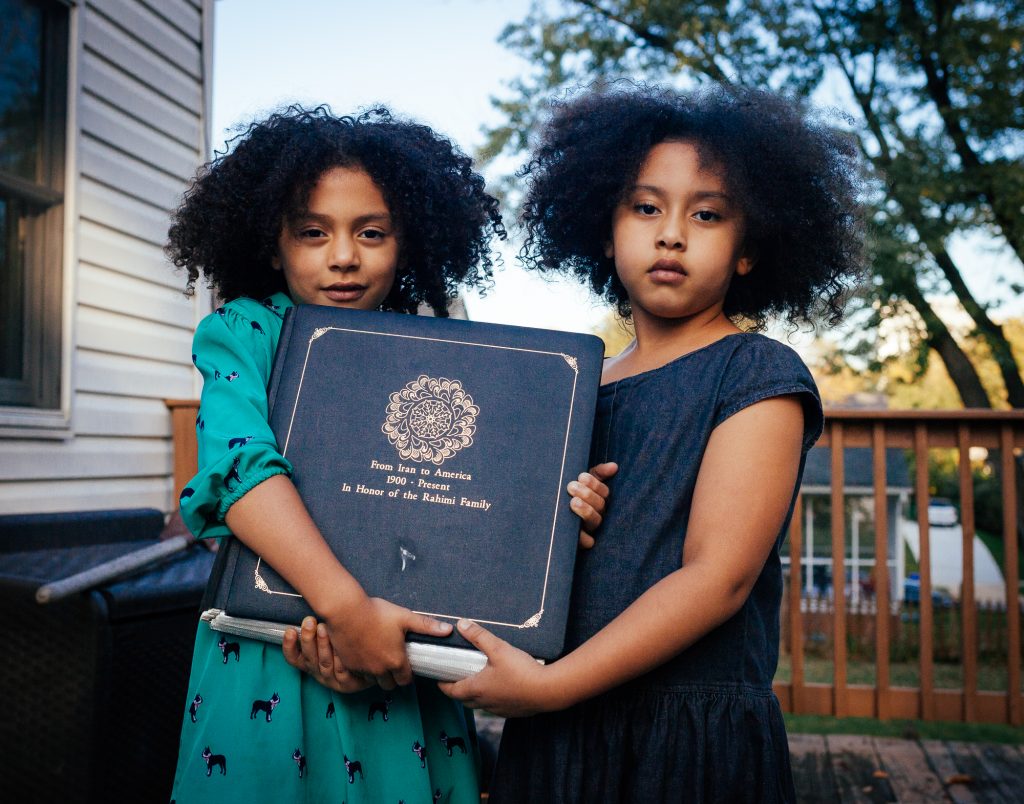

Childhood

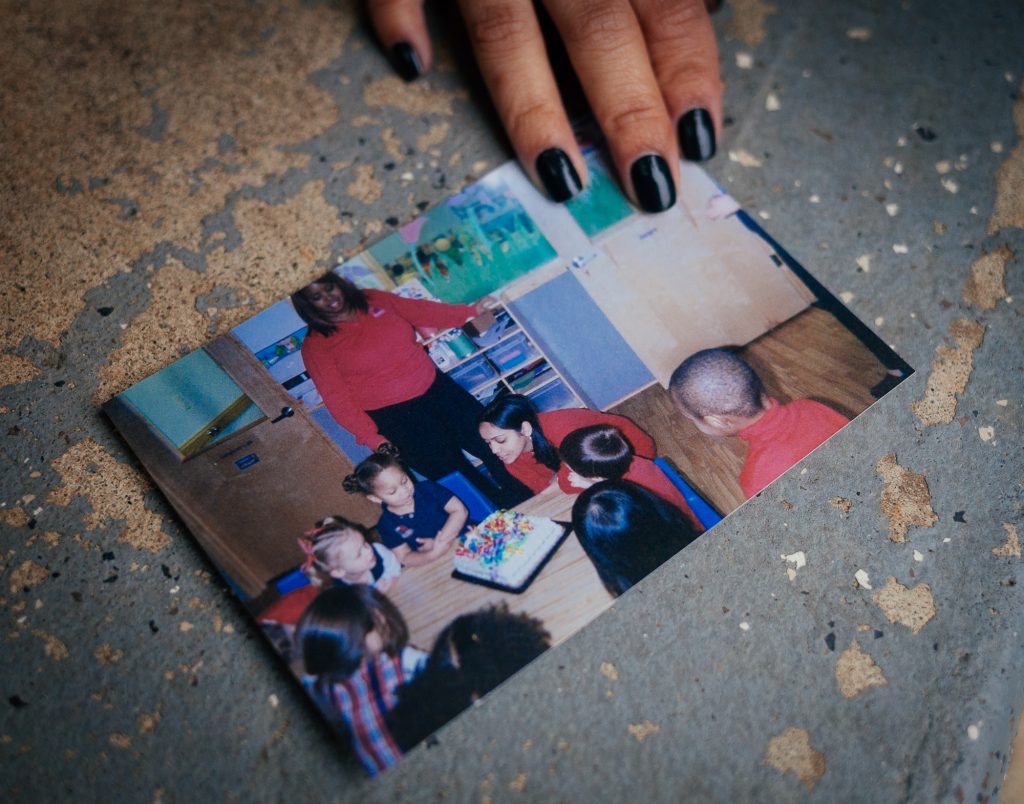

Sabato’s father met his mother, an industrial designer, in the mall where he owned a toy store. Their son Sabato was born in 1985, and when he was only one year old, they moved the family to Miami, USA. Sabato believes they had many reasons to leave and did so when his father secured a visa and some money to start a company. Sabato’s parents imported Brazilian semi-precious stones. The belief prevalent in the late 1980s and early 1990s within the Hispanic community of the healing powers of crystals fueled their business. Sabato’s parents opened concessions in Sears stores throughout South Florida, where they sold these stones.

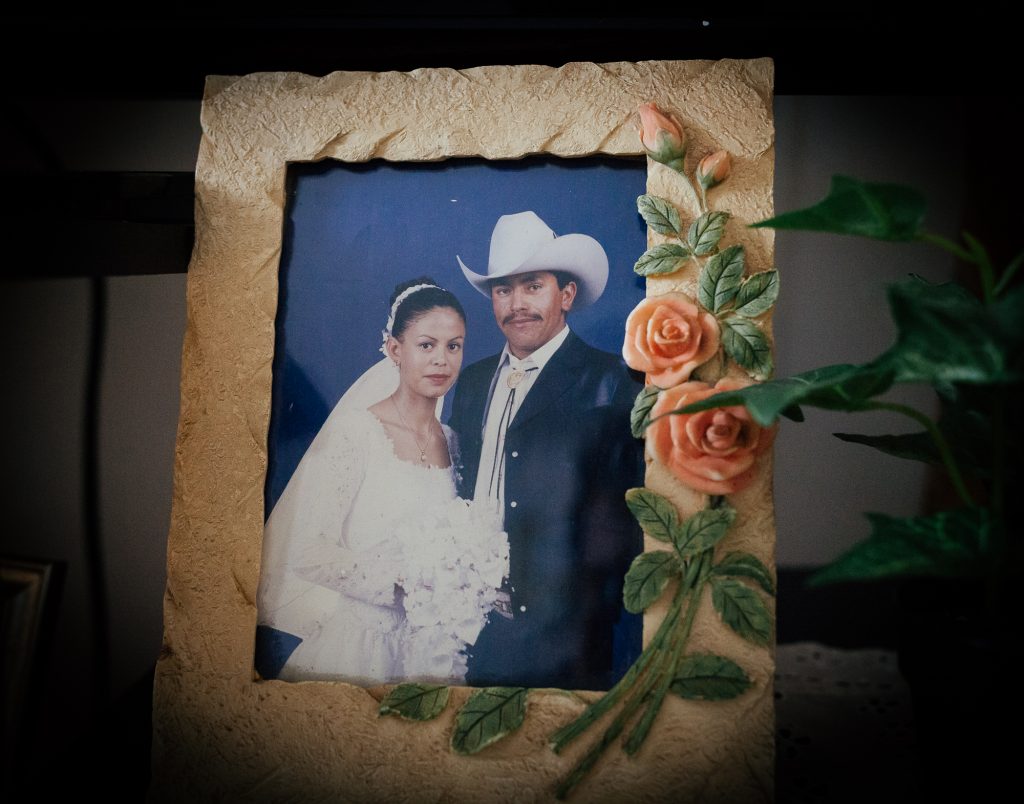

Separation

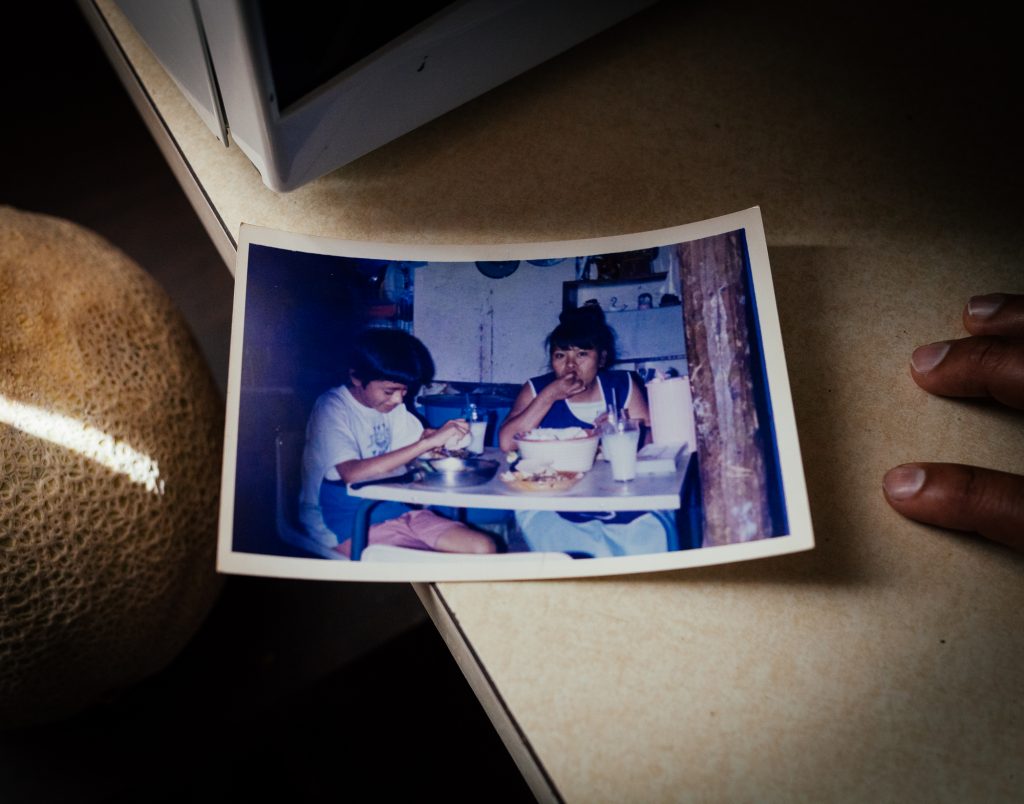

When Sabato was six years old, his parents separated. His mom moved back to Brazil, and Sabato remained with his Dad in Miami. When Sabato was in college, his father remarried, and he has a 10-year-old baby brother, “who is amazing.”

Sabato’s mother wasn’t around when he was a child, and he remembers that he went through five years without seeing her. Currently, he gets to see her a few times a year.

Miami

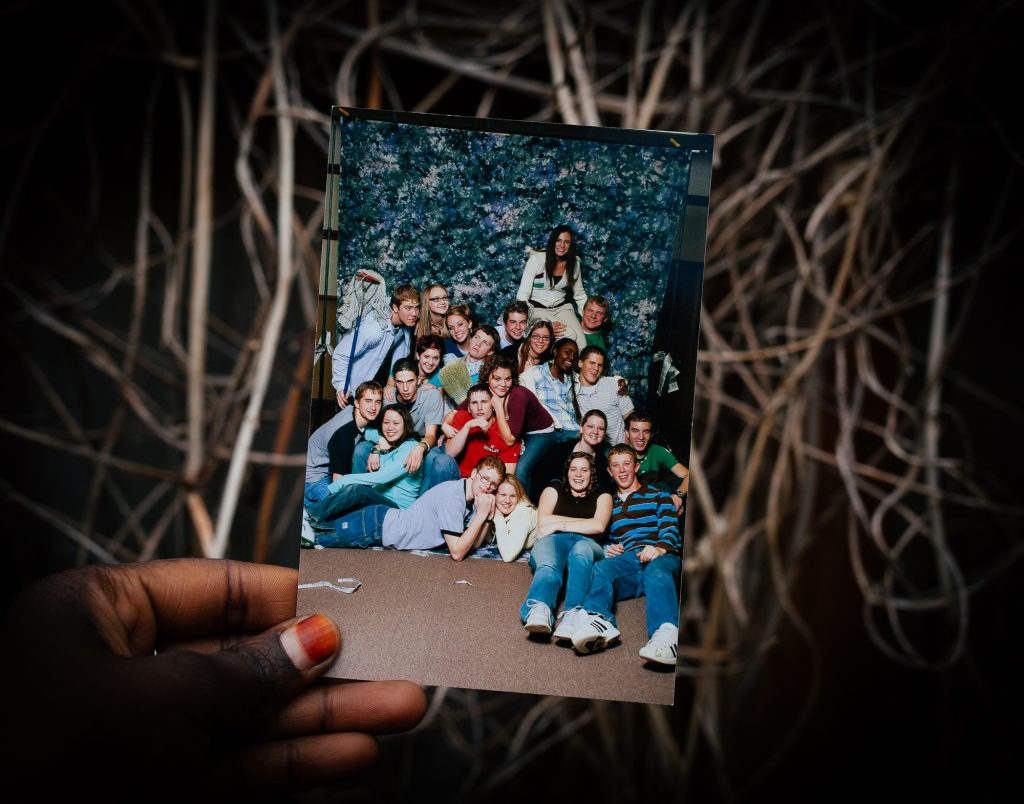

Sabato grew up in Miami’s “multicultural immigrant vibe.” where he was able to interact with classmates from all over the world. As Sabato got older, he started to hate the superficiality of Miami’s “new money.” Sabato recognizes how Miami is different today with a budding street art scene and independent cinemas. Still, it wasn’t like that when he was growing up.

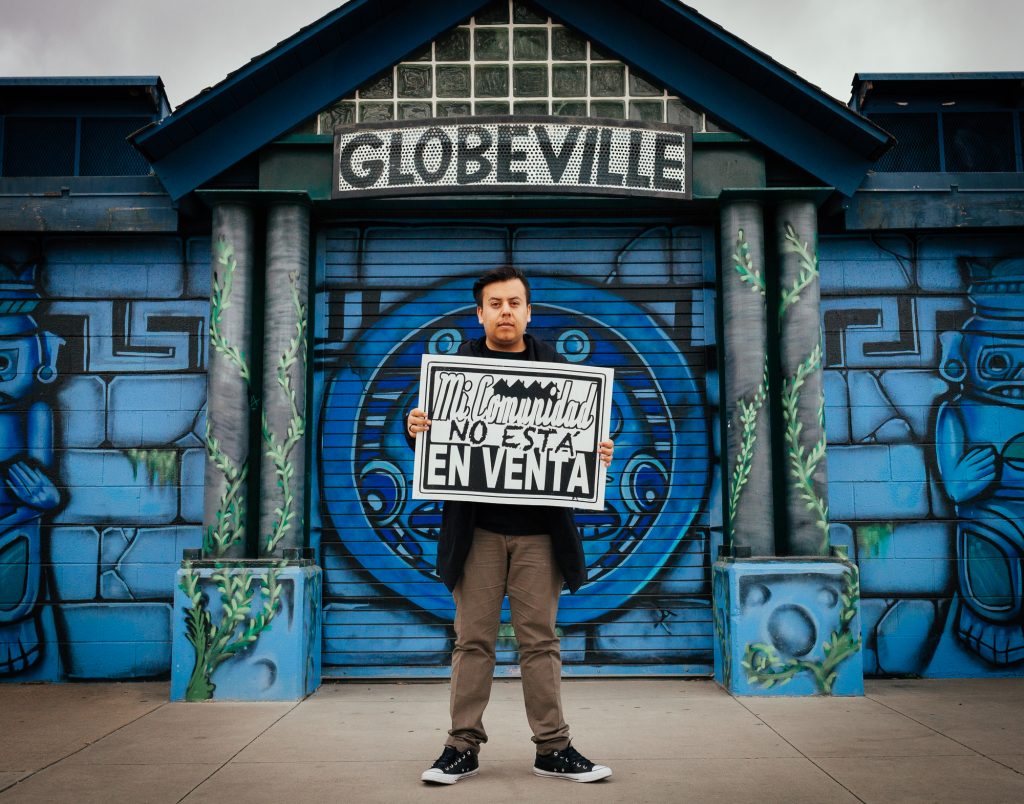

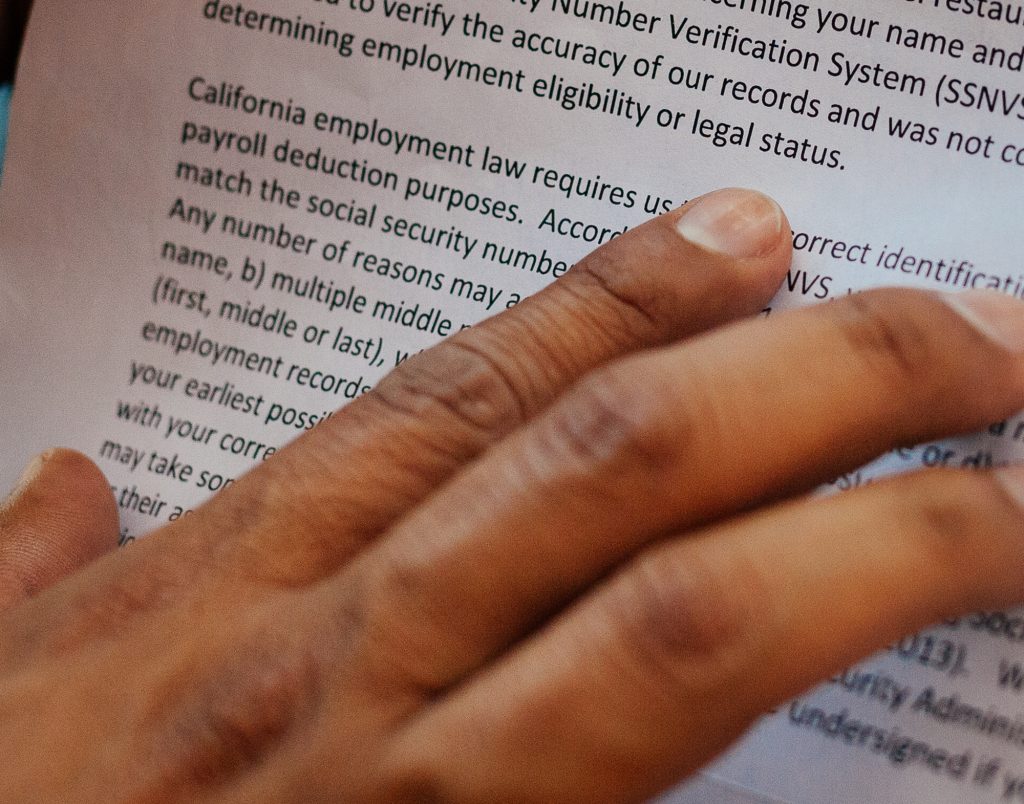

Undocumented

In the Miami of Sabato’s youth, so many people were undocumented. It was an easy place to get a job under the table. Like many of the kids he grew up around, Sabato didn’t know what the implications of not having papers were. Over time, he started to realize what it meant. Sabato couldn’t get a driver’s license but was able to secure a Florida state identification one day before September 11th, 2001, when the requirements changed.

“You become aware of these challenges. For people who grew up in the United States, it is just, ‘I’m 16, I’ll get my license’. These are things you assume you have access to, but you don’t.” (audio below)

Even though he heard that he couldn’t go to college because he was undocumented, he applied anyway.

“You continue being a part of the community: you have friends, do American things, but when it comes to certain things like employment or financial aid you can’t.”

Because Sabato knew he wasn’t eligible for financial aid, he didn’t apply for it when applying for college. He worried about potential implications if he told the school he was undocumented: the chance of deportation worried his father. After being accepted to Amherst College in Massachusetts, the reality of not having financial aid hit:

“Holy shit! I need to pay $50,000 dollars every year to go here!”

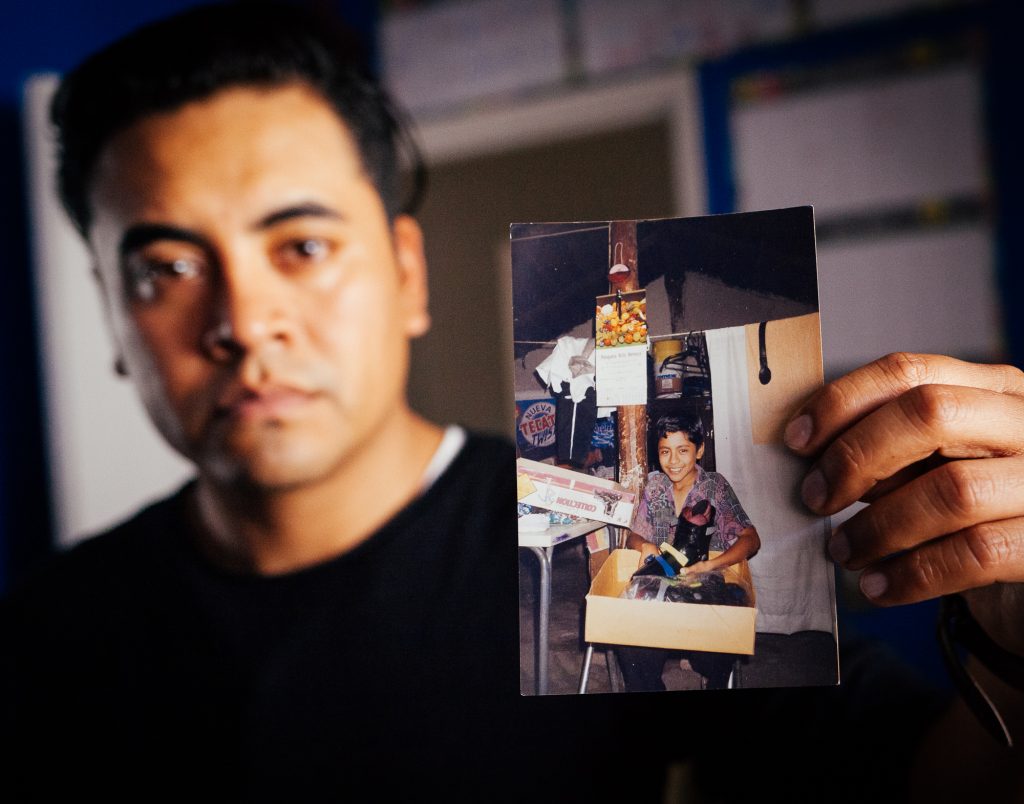

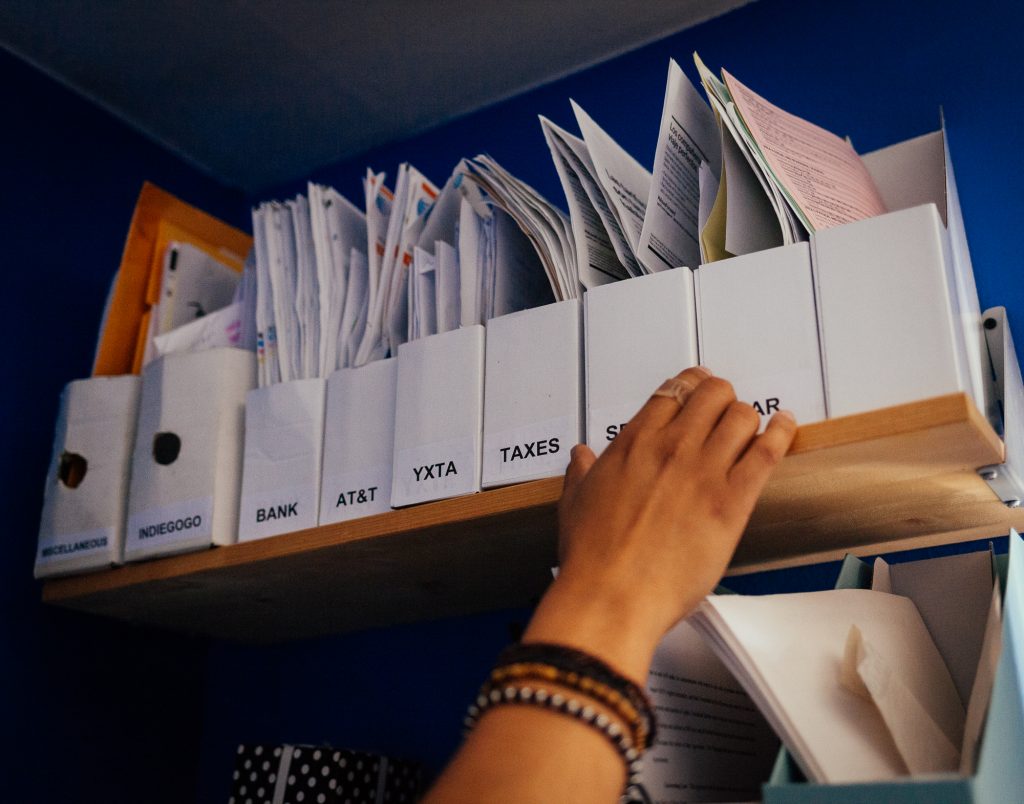

Hustling Pianos

Because of his status, Sabato couldn’t find a job that would provide him with a salary, so Sabato and his father started a business flipping merchandise from auctions on eBay. What they decided to flip stemmed from Sabato wanting a piano to learn classical music. When his father went to a piano distribution center to find out the cost of one, he realized he could sell them on eBay and make enough of a profit to pay for three years of Sabato’s university degree.

“Only five percent of undocumented people go to college. I’m so lucky to have overcome that – hustling pianos!”

DACA

Sabato remained undocumented until 2014. With the DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) program, the government deprioritized his deportation, and he received a work permit. Most paths to financial stability involve getting a full-time job, and finally, Sabato could do this. Here in Massachusetts, he showed his Brazilian passport, and that was enough to get a driver’s license. (audio below)

Massachusetts

In 2001 at the age of 18, Sabato fulfilled the dream of going to Massachusetts to attend college.

“I wanted to go to a place where it snowed, the seasons changed and it was more ‘American’ – I was tired of Miami. I knew if I went to school somewhere where it was cold, my family would hardly visit me. That was part of the calculation. [laughing]”

Living in Massachusetts made him appreciate and miss Miami; however, following graduation Sabato decided to stay in New England.

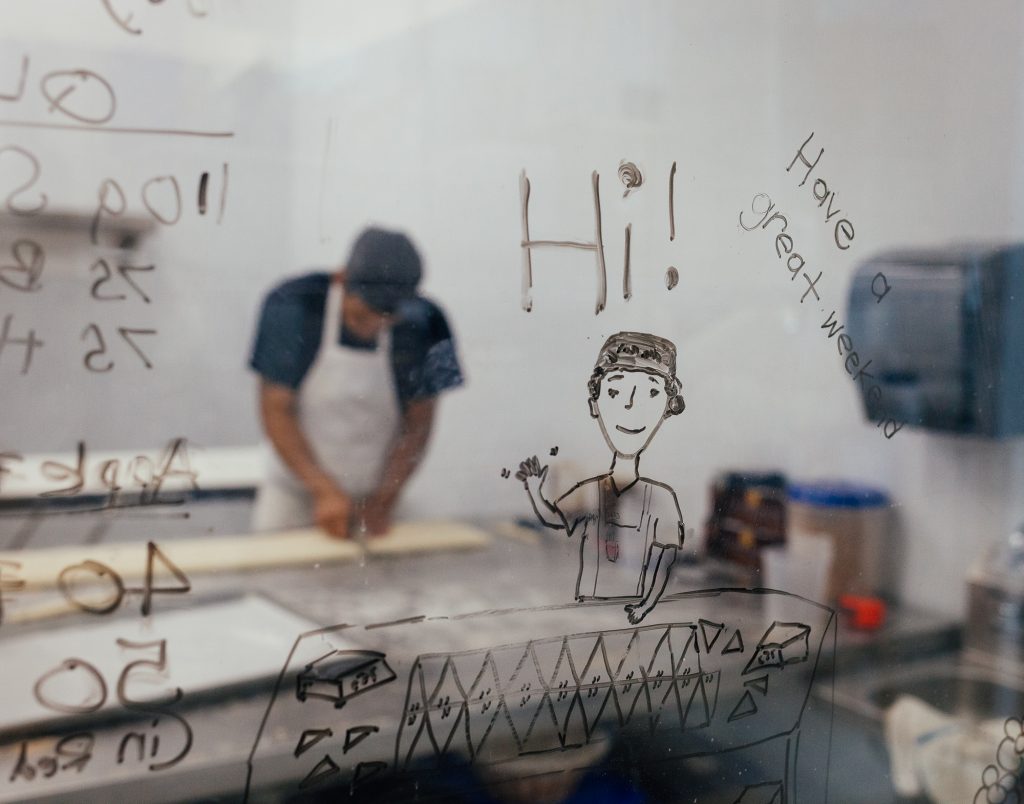

Sabato has always been creative. He remembers getting into trouble in middle school for drawing cartoons when he was supposed to be paying attention to the lesson.

At college, Sabato began taking portraits of his friends and doing video production. These two side hustles were extremely helpful considering that he couldn’t get a regular nine to five job.

Glitch Art

In 2011, a friend showed him a compact flash memory card in which the files were coming out glitchy. He was curious and fascinated by the missing parts and rearranged the pieces. Sabato began to create “glitchy” digital files on purpose [see the photos above]. This process of finding ways to corrupt or break photos or videos that he takes has become his artistic focus. His art has been shown at the Tate in London as well as featured in Time magazine. (audio below)

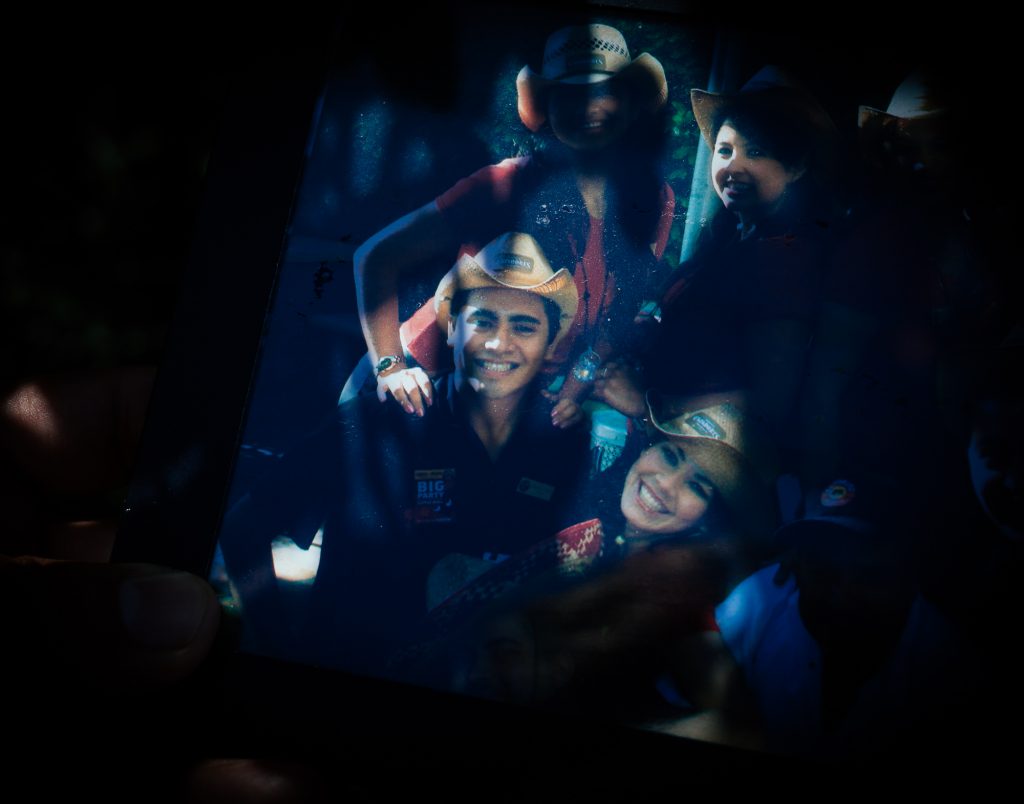

Meeting Meredith

It was through art that he met his wife, Meredith. Sabato was shooting an art show in Connecticut, and Meredith was one of the vendors. When he took her portrait, there was an instant connection. He still loves taking her photograph.

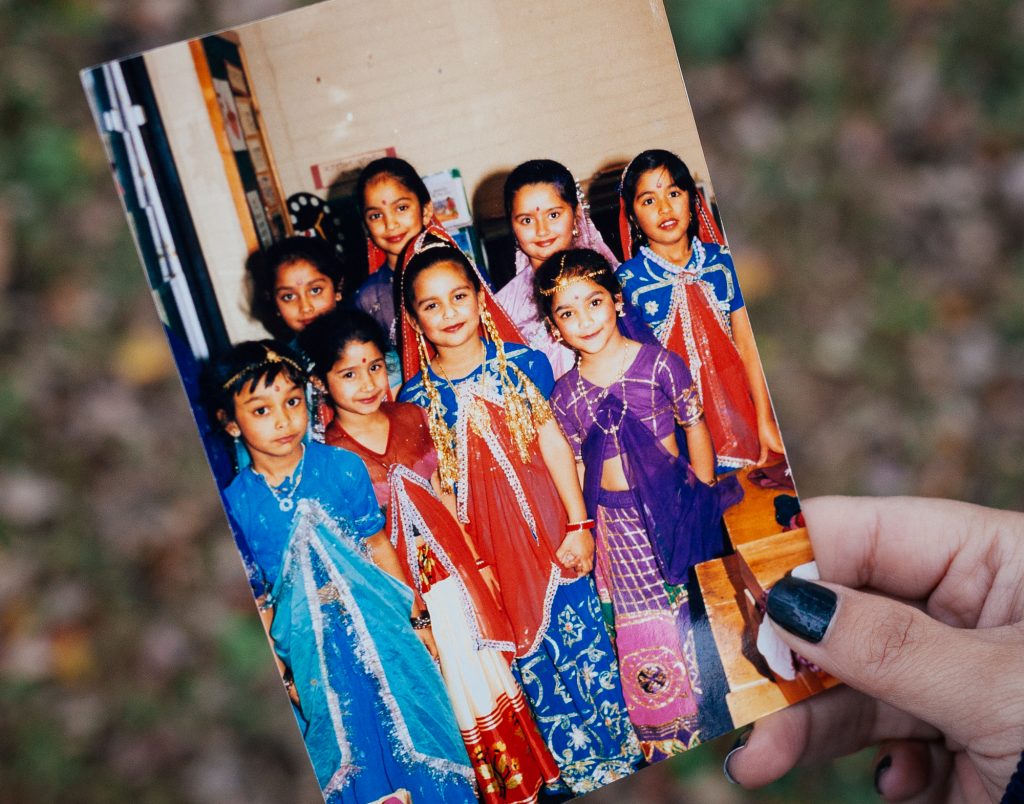

From what Sabato has observed, people who grew up in the States have all read the same children’s books or watched the same shows. He grew up reading Brazilian comic books and the bible in Portuguese, so some American pop-cultural references go over his head.

“I grew up differently and had different experiences.” (audio below)

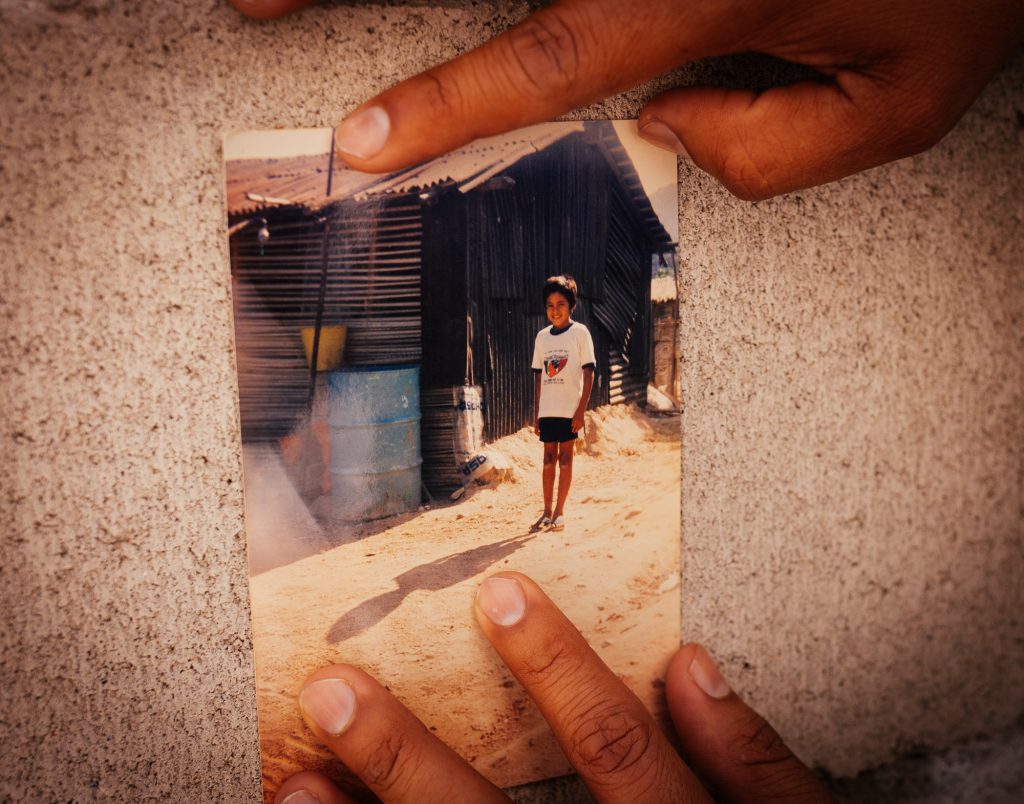

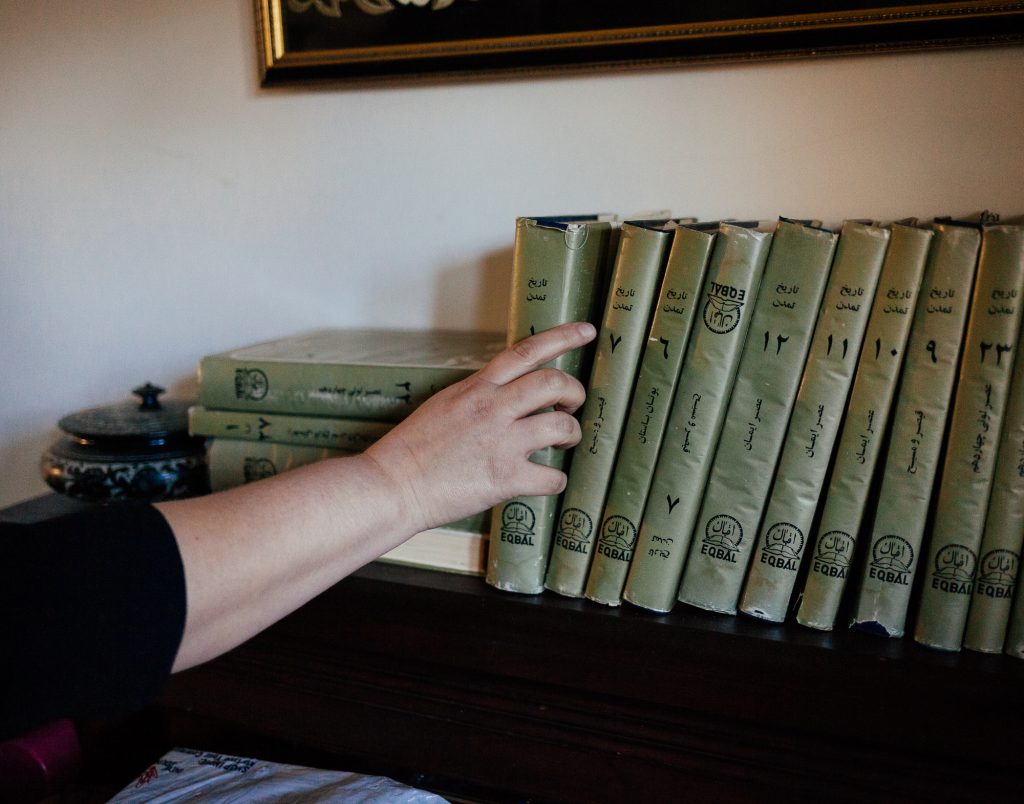

Roots

He feels lucky that his father was persistent in his wish that Sabato would speak Portuguese as a child and maintain his language. He knows that for many immigrants his age, this is not the case. Throughout his childhood, Sabato translated for his dad, including the sermon at church and any legal documents.

Soccer played an important role in keeping Sabato connected to his roots.

“In 1994 the World Cup was held in the United States, and it was a big deal. I was really rooting for team USA. Brazil played the US in round 16 and I was rooting for the US even though Dad and everyone watching with us were rooting for Brazil. The US lost 1-0 and Brazil ended up winning the World Cup. That’s the first time I was proud to be Brazilian – being with that group, watching old games from the 70s with Pele and all the classic Brazilian soccer heroes. I’m part of this shared history which makes me really happy. In 1998, when Brazil went to the finals and lost to France, I was crying my eyes out.” (audio below)

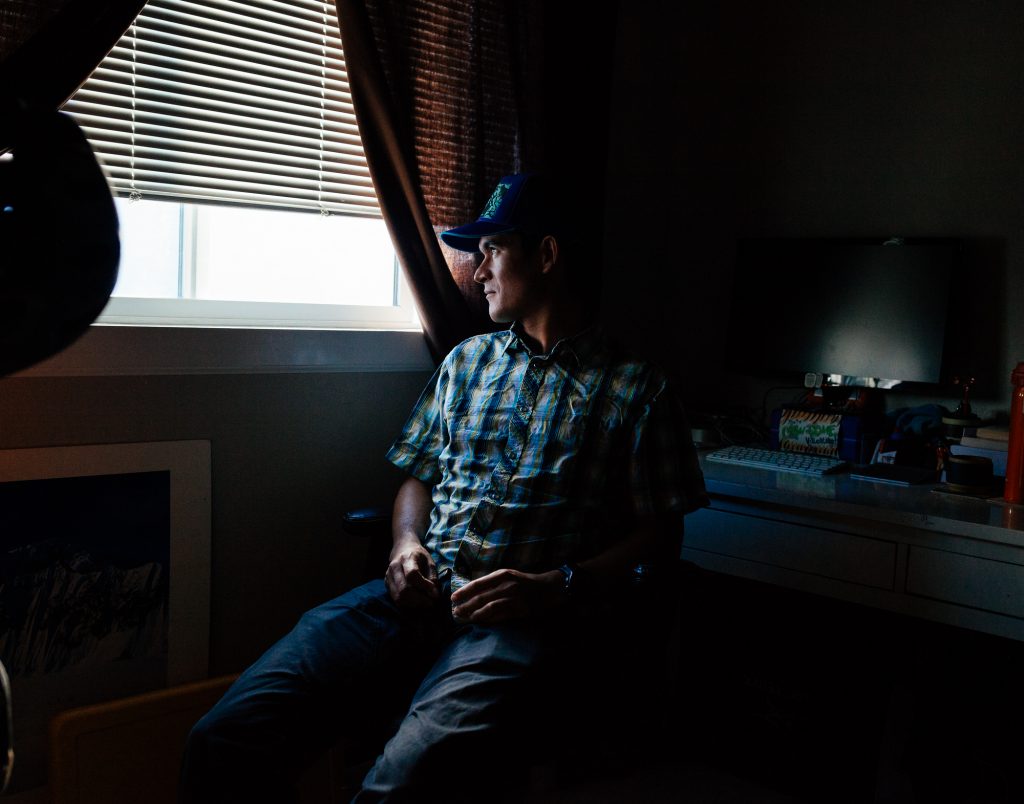

Sabato feels like his Brazilian identity is becoming more defined with age, especially since moving to New England for college. Massachusetts is where his identity coalesced, and for the first time in his life, he felt “exotic.” (audio below)

Future

Sabato currently creates advertorial content for personal injury lawyers as his day job. In the future, he dreams of going to graduate school for photography or digital arts/media and eventually working full-time as an artist.

“I dream of one day being in a position where I can live off my work.”

*Update: Since the interview, Sabato got his green card through his marriage to Meredith, quit his job with the personal injury lawyers, and has been working as a full-time artist. You can find out more about Sabato’s incredible work on his website.

#FINDINGAMERICAN

To receive updates on the book release and exhibition of “Finding American: Stories of Immigration from all 50 States” please subscribe here. This project is a labor of love and passion. If you would like to support its continuation, it would be greatly appreciated!

© Photos and text by Colin Boyd Shafer | Edited by Janice May & Kate Kamo McHugh. Quotes edited for clarity and brevity.