Mexico

“I don’t have many memories of Mexico.”

Abi’s memories of life in Mexico are vague – it’s hard to tell what is a memory and what is from the stories her mom has told her. She knows they were poor, and eating from the street vendors was a luxury. This one lady would always come by on a bicycle selling tamales and hot chocolate. Abi would run out to her. The lady would have a huge smile and she never expected Abi to pay her anything – she could see that Abi was poor and hungry. That woman’s kindness, Abi has never forgotten, and it inspired her to want to do good for others too. (audio below)

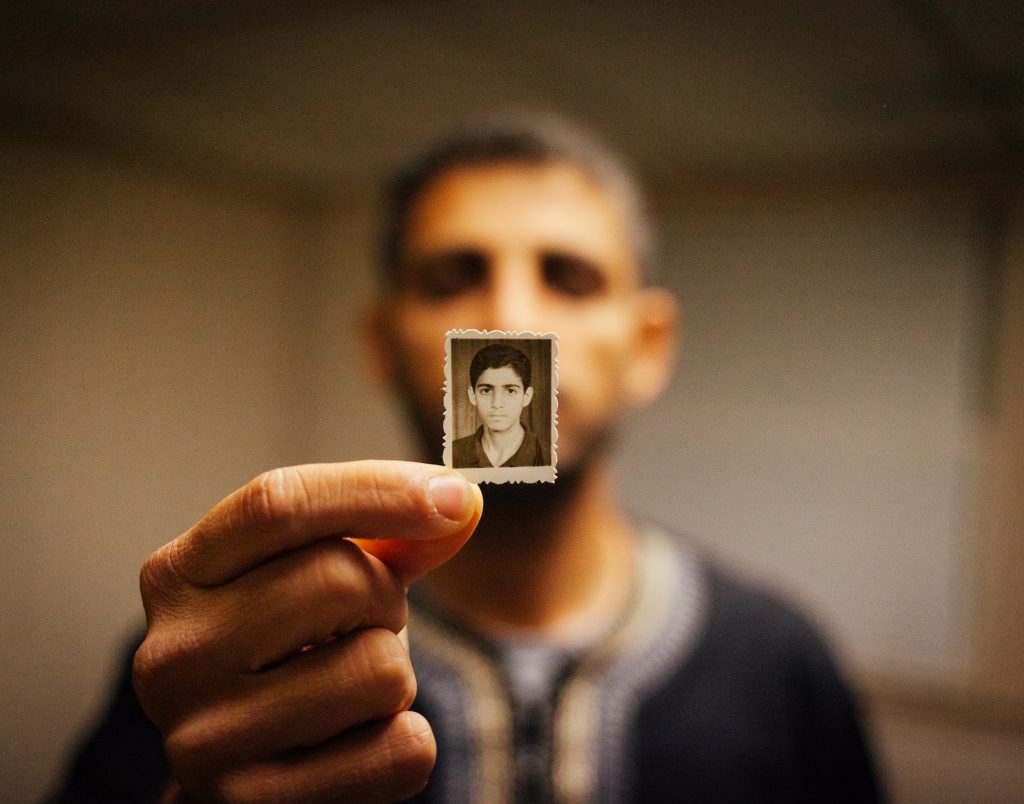

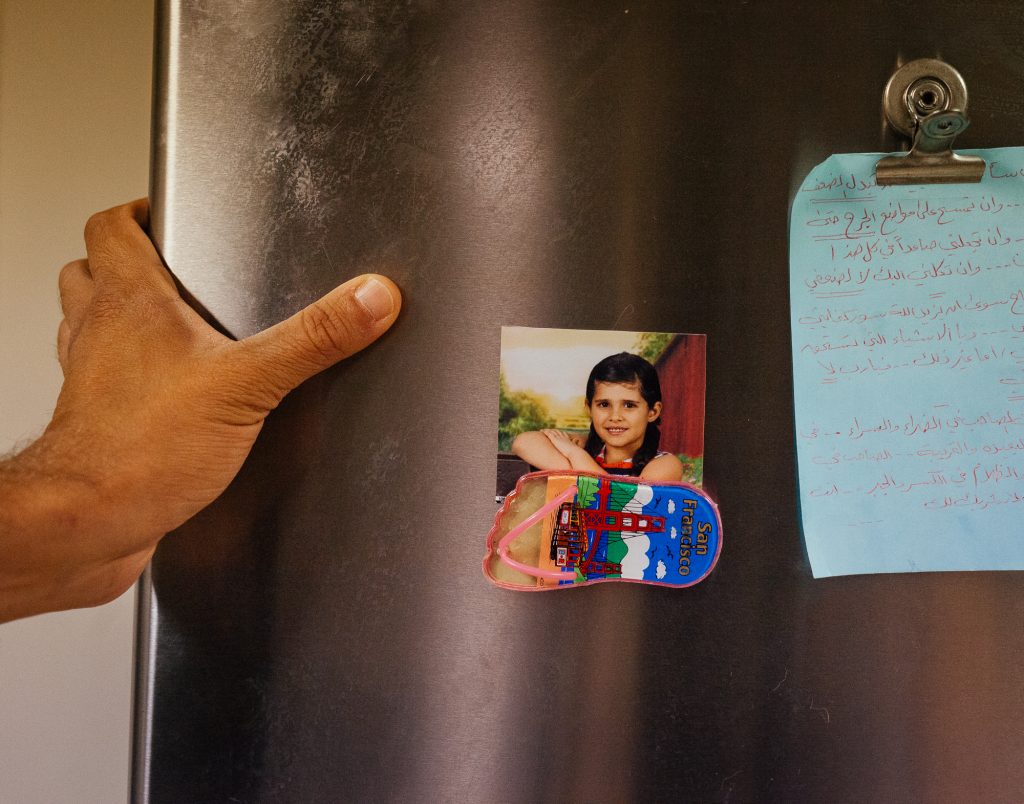

Abi remembers how close-knit her family was in Mexico and has memories from the day they left. It had been almost two years since they last saw Abi’s father, who was already in the US. Leaving felt spontaneous – Abi had no idea her last day in Mexico, was her last day. She left wearing a black Bart Simpson backpack, with a cardigan, a coloring book, and crayons inside. (audio below)

Leaving

She remembers how sad leaving Mexico was for her mom. Abi was put on a bus which took her close to the border, then she got in the van of her mom’s friend, and this woman brought Abi across the border, saying Abi was one of her daughters. (audio below)

Abi’s mom tried to cross on her own and got caught and sent back to Mexico by border patrol the first time. This meant that Abi, four years old, had to stay two weeks in a hotel room with this stranger who crossed her and her own three kids. Abi remembers the smell of cigarettes and combing the lice from the children’s hair. For these two weeks, her parents didn’t know where Abi was and they were “freaking out”. Then one day, the woman told Abi to get dressed and get in the van. That was the day Abi finally got to see her dad for the first time in almost two years. Three weeks later, her mom crossed the border without getting caught and met up with them.

They stayed in Colorado for a few months, where an aunt was living. Adjusting to the United States was hard for Abi’s mom, and job opportunities were scarce. An uncle had a construction business down in Mississippi, so they headed there to try it out. Abi’s dad was a welder in Mexico, but in America, he worked in construction and for a furniture business. Her mom, the daughter of a seamstress, had always worked office jobs in Mexico. She always said she would never sew like her mom did but a factory in Mississippi was hiring, and she has been sewing for them ever since. Both of Abi’s parents had to work night shifts.

Abi’s mom, in particular, has endured a lot being away from her family.

“To be able to fight as hard as my mom has to raise my sister and me is incredible. We are family people, and she didn’t have support.”

Adapting

It wasn’t easy for Abi to adapt to school in Mississippi. She started kindergarten in New Albany, and only three other Hispanic families had kids at that school. She always felt like she was bringing weird-smelling foods or weird-looking drinks to school.

“We don’t stop being Mexicans just because we moved to a different country. It was hard to find friends that wouldn’t look at you weird. It’s really close-minded here. The Hispanic community is large now, but back then, it was small, so we were ‘foreigners.’”

There also wasn’t an ESL (English as a Second Language) teacher at her school to help her.

“I remember for two years, all they did was stick us Hispanics in a room and let us draw on the board.”

But Abi will never forget one teacher, Ms. Tammy Hill, who would try her best to help despite the language barrier. It was because of Ms. Hill that she learned English in nine months. (audio below)

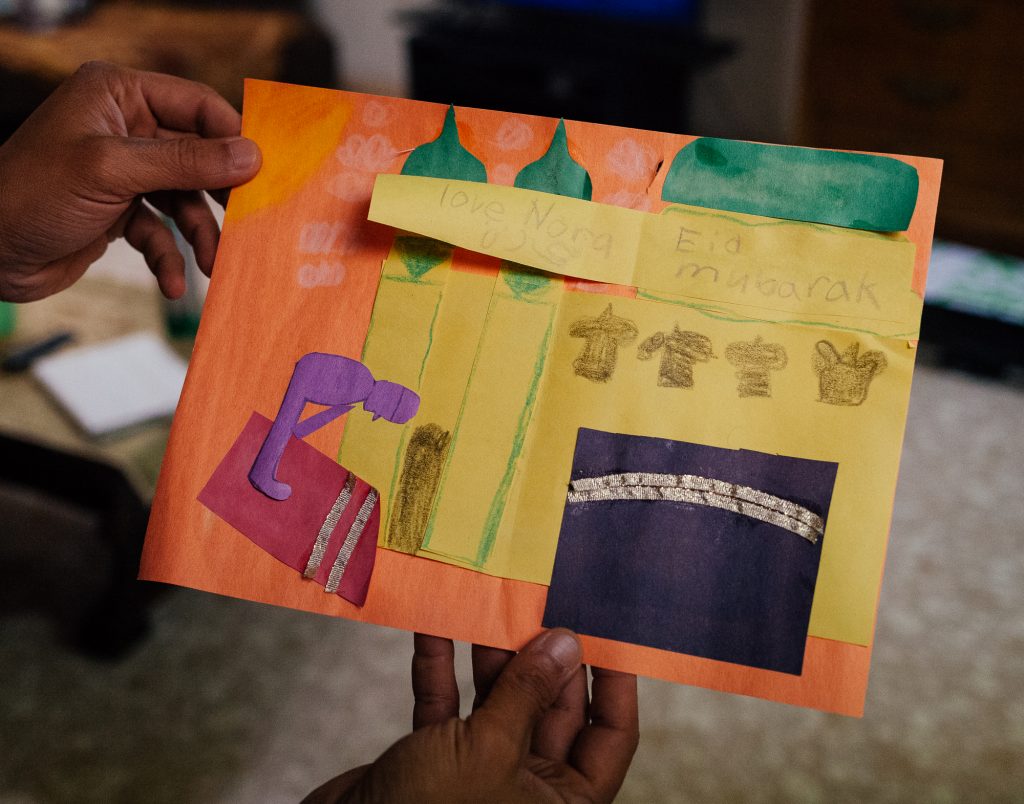

Abi always felt excluded due to religious differences. Most of the people in this part of Mississippi are Baptists, whereas her family is Catholic. She felt like people were always asking her questions about the bible, and she couldn’t believe they do “bible drills”. (audio below)

Community

“I’ve always been a loner.”

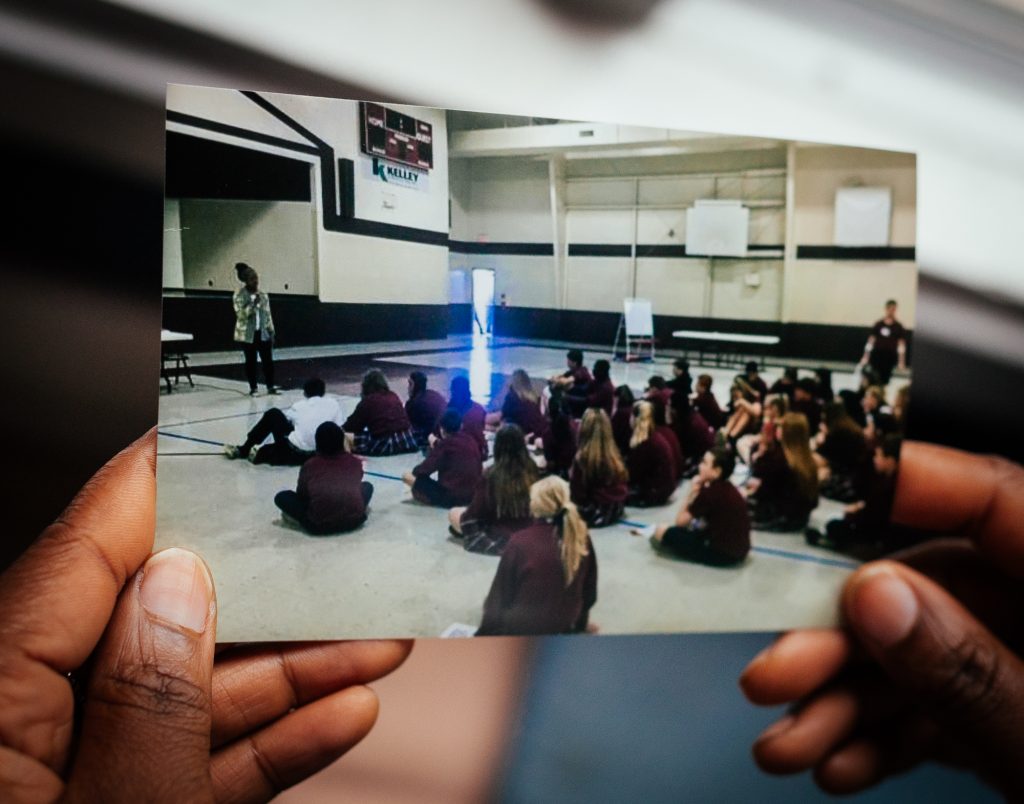

Her mom thought Abi needed friends and signed her up for Girl Scouts. The leader, Miss Kareen, was the first white person Abi remembers truly accepting her and the other Hispanic kids. Her first friends, her age, were Miss Kareen’s daughter and niece.

“They were the first American family that accepted us for who we were. They didn’t question why we weren’t speaking English or why we couldn’t afford this or that. Girl Scouts will always hold a special place in my heart. It gave me the confidence I never had as a kid. We were all the weird kids, and we bonded over our weirdness.” (audio below)

Stokes is a general store off the highway that’s been around for many years. It’s where Abi’s parents would go to cash their work checks. They couldn’t cash them at most places without ID, but Mr. Stokes would cash them. He asked her family what they missed from home, and they said tortillas.

“There was nowhere here that you could find tortillas. Mr. Stokes said ‘give me a list,’ and he would order Mexican products to bring into the store. He was one of the few people who supported immigrants in this community. He always told me I could take one candy that I wanted when my parents cashed their checks.” (audio below)

Like Miss Kareen, Mr. Stokes, who passed away recently, treated Abi’s family with respect and kindness.

Dreams

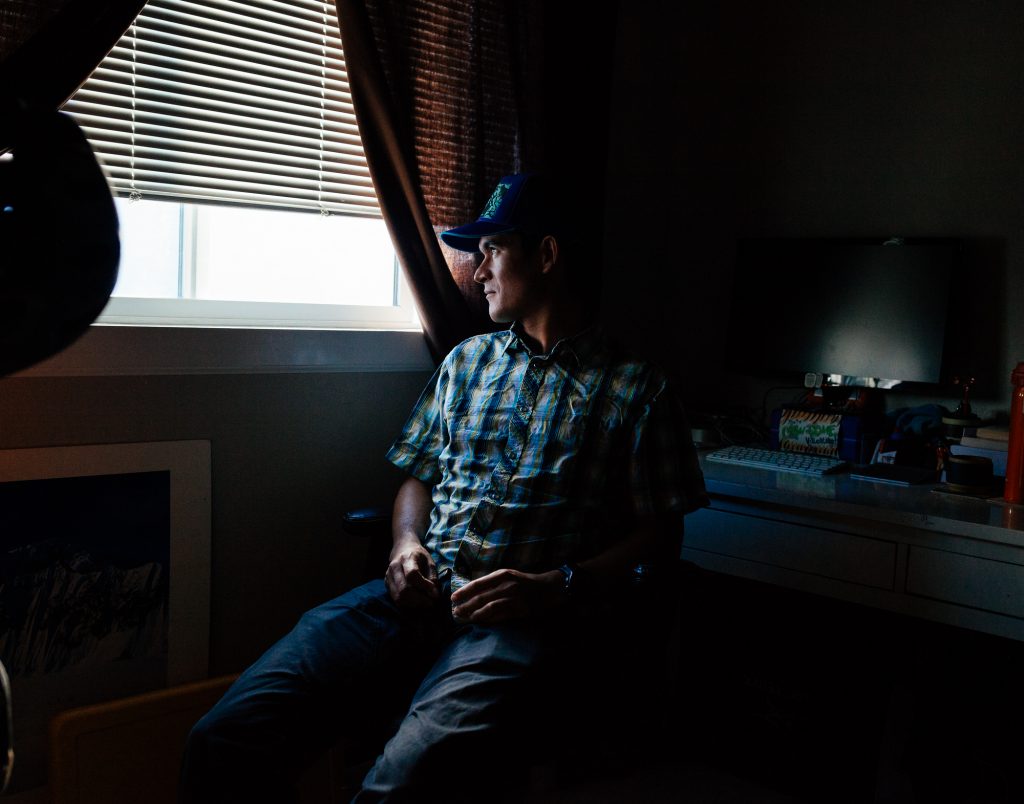

From an early age, Abi knew she wanted to be a medical surgeon. With her high school counselor’s help, she took all the classes she would need to get accepted, and made excellent grades by “working [her] butt off.” It was two months before she graduated high school in 2013, and many universities had sent her letters of acceptance (including her dream university, Stanford), when Abi came to realize that because she didn’t have a social insurance number, so she wouldn’t qualify for any scholarships. Abi wasn’t going to be able to afford university, which was one of the hardest realizations she has ever had.

“You spend your entire senior year planning out your life and I wanted to go to Stanford so bad. That’s all I ever talked about.”

She settled for community college, and because she was undocumented, she was paying out-of-state tuition. After the first semester, she dropped out.

“I couldn’t get it out of my mind the fact that I had failed myself.” (audio below)

Medical school wasn’t in the cards for Abi. She thought about studying criminal science, and then joining the police force – and then found out she couldn’t do that since she wasn’t a US citizen.

“I went into a depressed state. I always knew something was off about me but I used to be one of those people who said, ‘just think happy thoughts, and it will go away.’”

She didn’t know what to do with her life, felt very alone, and was hopping from job to job. Then she met her partner, he helped her a lot, and she started to see “the light at the end of the tunnel.”

Grandma

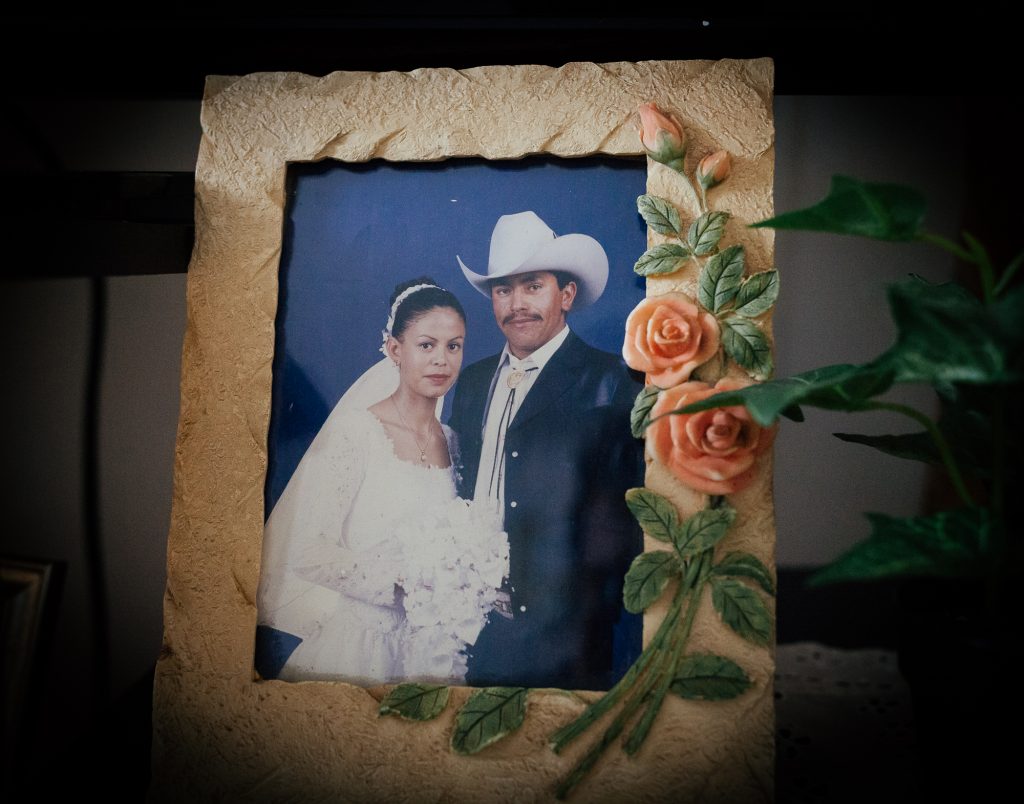

If there is one person who has inspired Abi the most, it would be her grandma. She was orphaned at a young age, married young to an abusive husband, and got divorced (which was highly unusual at the time).

“My grandma is the epitome of strength and resilience. She put all her kids through school as a single mother. She would find ways to have fun and never focus on the negative.” (audio below)

When Abi left Mexico she thought she would never see her grandma again. Luckily, one decade after she arrived in the US, her grandma got a tourist visa to come to Mississippi and attend Abi’s graduation. Her grandma makes a green mole from scratch and snuck in some spices to make sure Abi got to eat her favorite dish.

“When I see her, it is like we haven’t missed a day. She’s just the light in my world. If I can be half the woman she is I’m doing something good. She forgets a lot of things because of her age, but she never forgets someone’s birthday.”

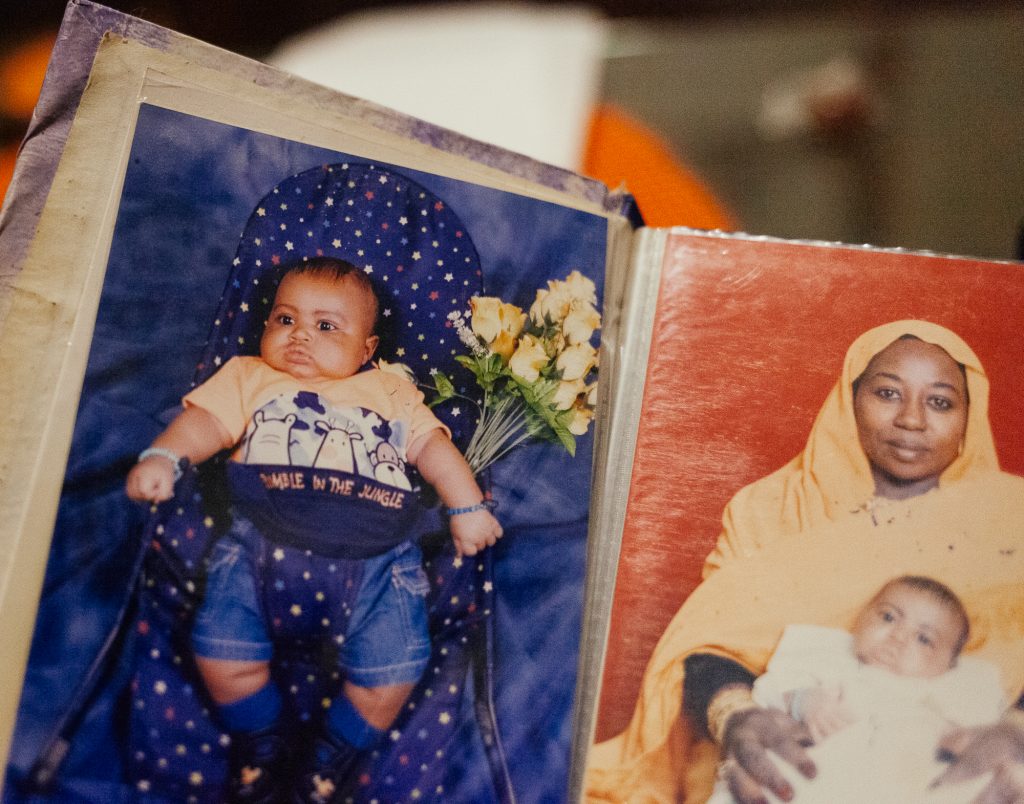

Although Abi couldn’t go to medical school, she still managed to find employment in the medical field. It started with a job in 2014 at the hospital doing newborn photography. Finding a passion and love for photography helped her get out of her depression.

After the hospital, she started working at a dental office. Two Italian American dentist twins, Ronnie and Donnie, really believed in her.

“I didn’t know anything about being a dental assistant, and they hired me.”

Future

Abi feels like she is at a bit of a fork in the road and isn’t exactly sure what she is going to do next. She’d like to go to dental school, ideally at Ole Miss.

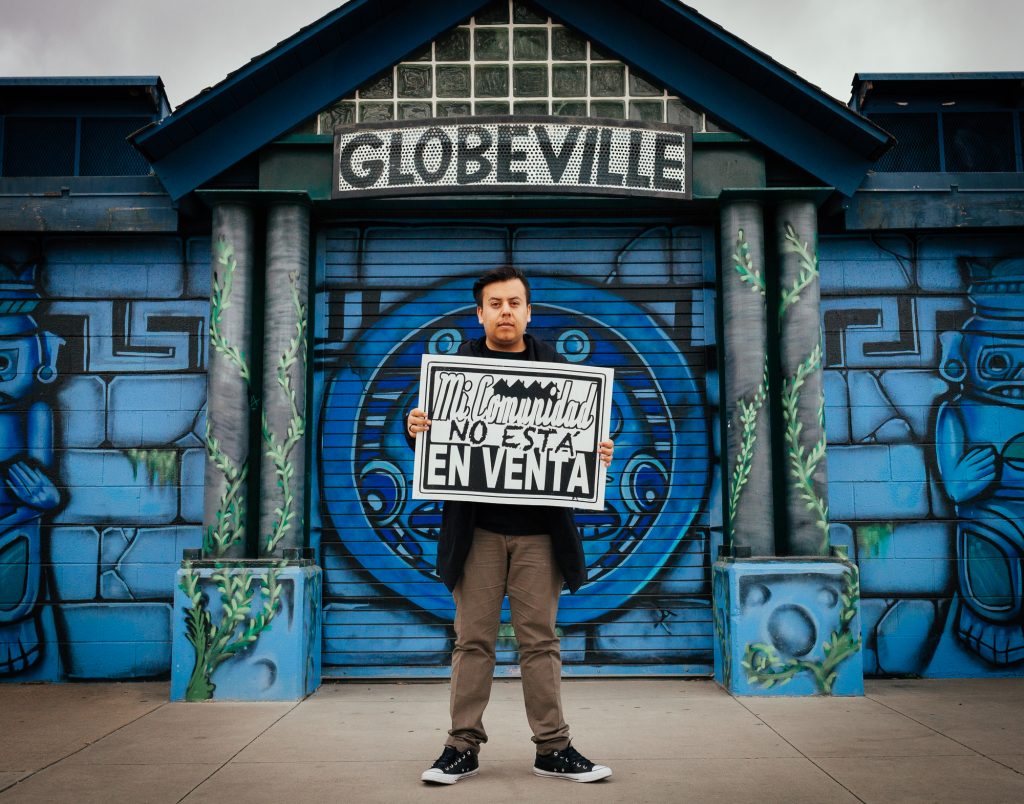

Even though Abi’s been in Mississippi for almost two decades, the fact that she isn’t from there is something she is reminded of regularly.

“To me, this is my home. New Albany is the first place I made my memories in the US. It doesn’t matter how excluded they make me feel; this is always going to be my home.”

Still, Abi believes that her generation is changing a lot of things here and thinks the future is bright.

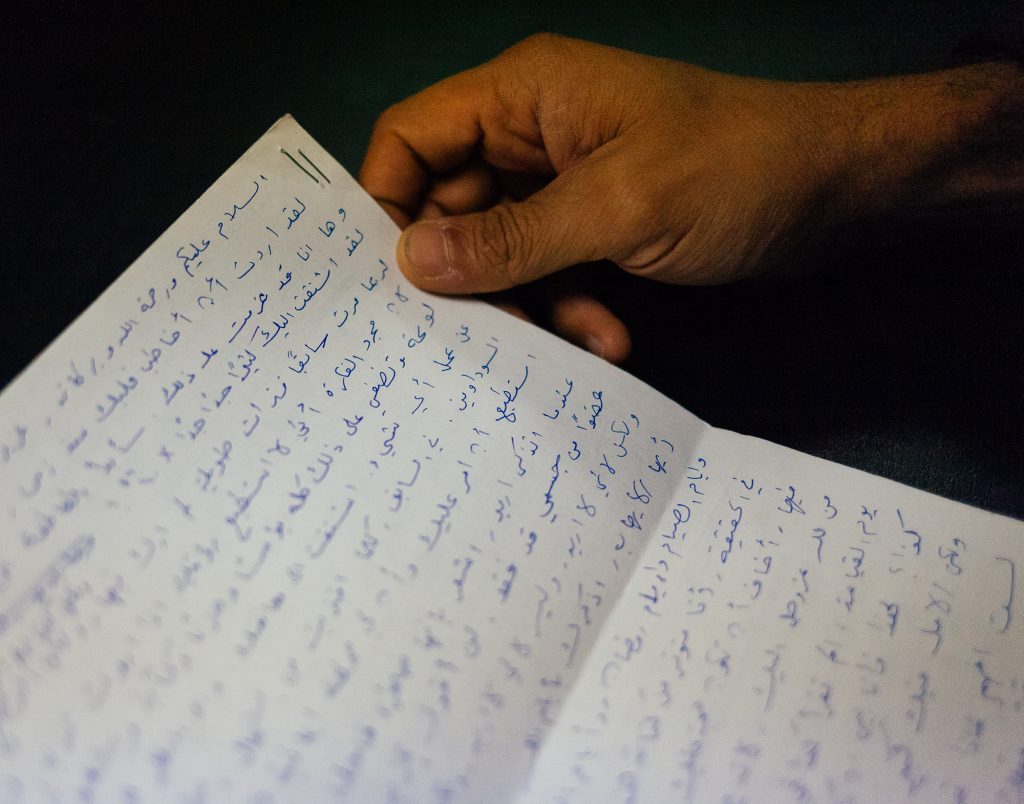

“Here in Mississippi, we need to learn how to accept immigrants. We came here because we wanted a better life. If Mississippian people were to open up their doors and listen to our stories, they could start to understand that we aren’t here to invade or take jobs. We are all just people, and we are trying to make life happen for us too. I hope and pray that everyone learns to respect others, who may not look alike, sound alike, or pray alike. We are in the “bible belt,” and if we really are Christians, then we need to act like it. Immigrants should be included.” (audio below)

Abi hopes more people like herself will share their stories.

“I don’t think my story is particularly special from anyone else that has come to the United States to try and make a new life.”

Abi also thinks too many people either try to forget that they came from somewhere else. She doesn’t want to forget her roots.

“Even though I was four years old when I came here, Mexico is still a part of who I am.”

#FINDINGAMERICAN

To receive updates on the book release and exhibition of “Finding American: Stories of Immigration from all 50 States” please subscribe here. This project is a labor of love and passion. If you would like to support its continuation, it would be greatly appreciated!

© Photos and text by Colin Boyd Shafer | Edited by Kate Kamo McHugh. Quotes are edited for clarity and brevity.