Village Life

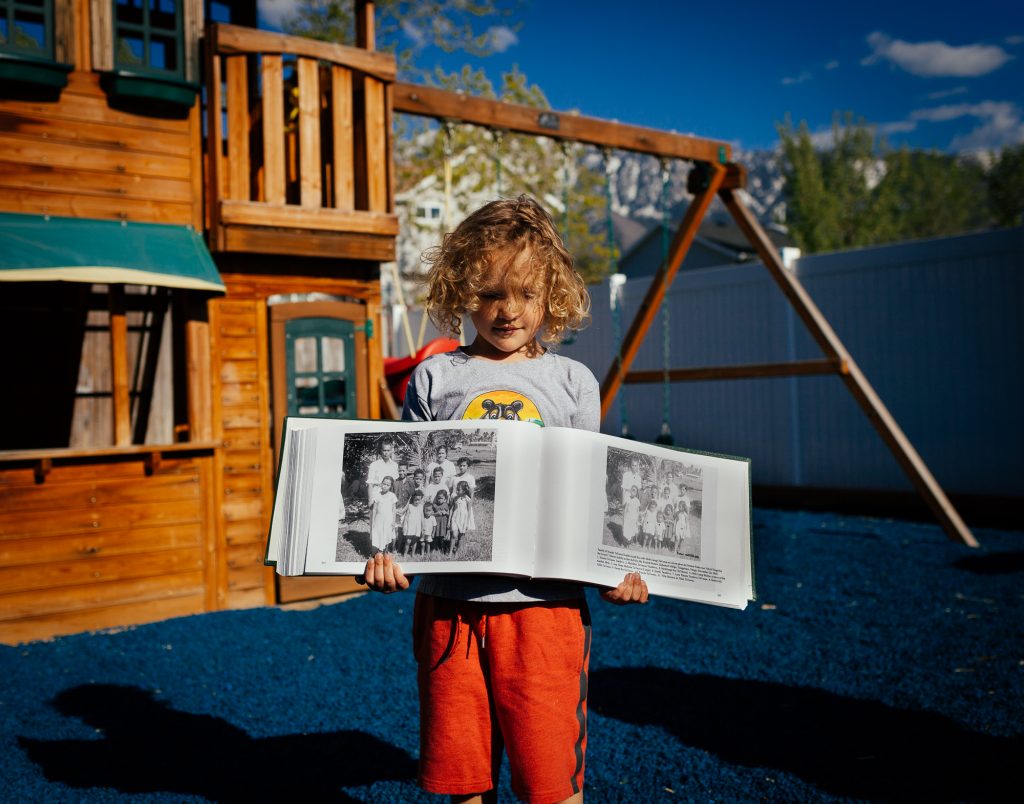

Joel grew up in a family of 12 children in a small village in Tonga – one of the smallest island countries in the world, with a population of a little over 100,000 people. In the entire village, there wasn’t a single car, so everyone got around by walking or horse and buggy. Joel would often fetch water from the village’s only well; there was usually a long line. He showered at the beach and washed off the salt using rainwater collected from the roof. Joel doesn’t remember wearing shoes until he left the island at age 15.

“I only had one pair of shorts, and we had to wash them every few days. We didn’t have a washing machine. I was the washing machine!”

Responsibility

Joel’s mom stayed at home to care for her 12 children. It wasn’t easy to make sure everyone had something to eat. Despite his family’s lack of money, Joel had a lot of fun as a child and doesn’t remember having many worries. He had never been anywhere else, so he didn’t know that he had less materially than many other children outside of Tonga. In their home, Joel’s seven sisters got the beds, and the five boys all slept on the floor. The children had a lot of responsibility from a young age, which included farming and many chores. (audio below)

Faith

Joel and his siblings had a religious upbringing.

“The people on the island are very religious. Sunday is the day of rest. It’s the law of the land. In Tonga, religion was so important.”

Joel’s father taught band and choir at an American school connected to the Mormon Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He made sure all 13 of his children could play an instrument. Joel learned the trumpet and has fond memories of the whole family caroling around the community at Christmas. Even though Joel’s father was a leader in the Mormon Church, he was often invited by the other denominations to come and compose music for their services. Joel has fond memories of riding on the back of his father’s horse to visit the other churches.

“My dad was serving other churches but never getting paid with money, just by food. I always liked to go with him because they would feed us well.” (audio below)

Outside of the Island

Joel grew up hearing regularly of Tongans leaving for America. His father originally came to the United States because of a calling in the Mormon Church.

“When he came back home, he was telling us about the freeways, lanes, and cars everywhere. He brought home all these second-hand jackets, and even though it is so hot, we were wearing them around and perspiring just because they came from America.” (audio below)

In Tonga at the time, high school was the highest level available, and Joel wanted a post-secondary education. He had a brother and sister already studying at Brigham Young University (BYU) in Hawaii, so he decided to join them there in 1970 to finish high school. Before arriving, Joel stopped in American Samoa to visit a sister. That was the first time in his life that he watched television.

“I was sitting right in front of that thing because I was amazed. All we had growing up was the radio, and most people didn’t even have a radio. Then when I went to Hawaii, I got to use a toilet and didn’t need to walk to an outhouse anymore. The luxury of life was nice.” (audio below)

United States

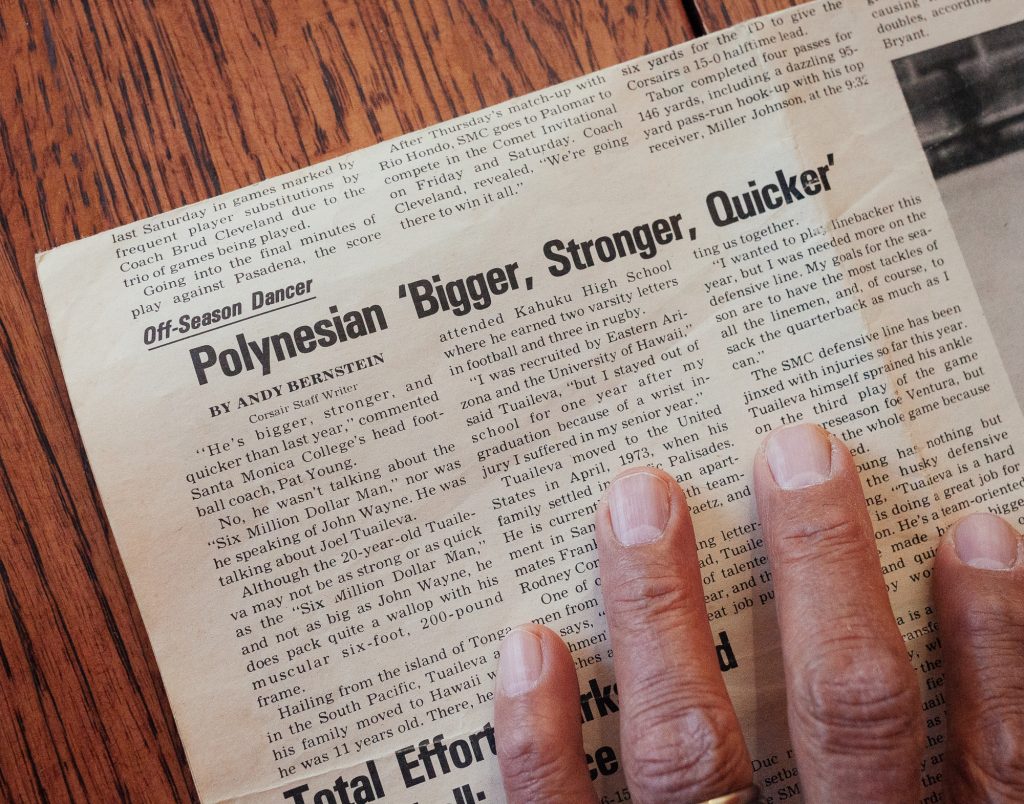

Joel used to play rugby while growing up in Tonga, so in Hawaii, he decided to give American football a try. It took him two years of playing on special teams to learn the game, but once he did, he was really talented. Joel became a respected outside linebacker and defensive end. After Joel finished high school in Hawaii, he moved to California to attend Santa Monica College and then Cal State on football scholarships. Football became an essential part of his life, but now he lives with regrets and pain.

“I just liked the physicality of football. It is the Polynesian mentality to like physical sports. Now looking back, if I could do it again, I would probably play golf. I had a knee replacement, and I have been having surgery on it. My shoulders, my ankles, I am always hurting, and it’s all from football and rugby. I just kind of live with it.” (audio below)

Joel attended college for five years, but he never graduated with a degree. His parents moved to California to join him, but when they couldn’t find work, Joel dropped out to help them care for his five youngest siblings. He and his father worked as landscapers, so his siblings could attend school.

Meeting Cindy

Joel thinks it was around this time in his life that he started making some wrong choices and grew disconnected from the church he had grown up attending. Then he met Cindy.

Cindy was born in Utah and living in California when she met Joel. Her father was teaching at a local College’s institute of religion, and Cindy was very religious. She regularly attended her father’s institute, where they had events for young single adults to learn more about the gospel. Joel’s sister also went there.

“I used to go pick up my sister, then I saw Cindy, and I thought ‘she is so beautiful.’”

Cindy went to a friend’s wedding, and Joel happened to be there, but as the entertainment. When Joel wasn’t playing football, he fire-danced and walked on fire with a Polynesian performance group. They were properly introduced at the wedding, and Joel made sure to get her number before it was over.

“Cindy was something special because she got me to go back to the church. I got away from the teachings of the church, and then I met her.” (audio below)

Moving to Utah

By this time, his siblings were older and were able to help his parents. Joel moved to Utah to be with Cindy.

Joel didn’t have a college degree, so he tried to find any work he could get. He had experience working with cement in Hawaii and California, so he did that, and at nights, he cleaned carpets and toilets.

“Coming from an island and a big family, everyone worked hard; I always knew how to work. Even though I had to work two or three jobs, I was able to handle it. My family just kept growing, and the more it grew, the more I had to work. We ended up having eight children. I had to work all the time.”

American Dream

Joel got his general contractor’s license and started his own business almost three decades ago. Joel likes working for himself because he gets to decide how much he works. It’s a small family business now, with most of his eight children working for him.

“It is the ‘American dream.’ We struggled along the way, but now I have time for anything I want to do. I don’t have to answer to anybody. Life is good. We aren’t rich or anything, but we are doing fine.”

Tongans in Utah

Joel thinks Utah is a great place to live and considers it home. All of Joel and Cindy’s children, except their eldest daughter, were born in Utah.

Today, more Tongans are living outside of the island of Tonga than in the country. In the 1950s and 60s, a lot of Tongans moved to Utah because of the Mormon Church. He likes how the church is service-oriented.

“It brings back the island mentality of everyone taking care of each other. The church expects you to be like that if you want to claim yourself as a good member of the church.”

The Tongan community in Salt Lake City gets together regularly for church services, funerals, and weddings. There are enough Tongans that they have their own wards within the Mormon Church. Despite this, Joel and his wife attend a predominantly white ward. Still, Joel tries to go to the Tongan meetings sometimes where they sing Tongan hymns, which he loves.

“It takes me home to listen to singing in our language.” (audio below)

“When I count in my heart, I count in Tongan. My wife said that when I talk in my sleep, I talk in Tongan. She doesn’t understand Tongan and always says, ‘Dang, I wish I knew what you were saying!’” (audio below)

Future

Cindy hopes she and Joel can retire and live the rest of their lives in good health, and able to enjoy time with their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. Cindy jokes how they have eight children, and she knows at least three of them will take care of them when they are older. (audio below)

Joel hopes his eight children and 23 grandchildren continue to not have to struggle the way he did. He also hopes they can all be strong in the LDS Church so it can bless their lives.

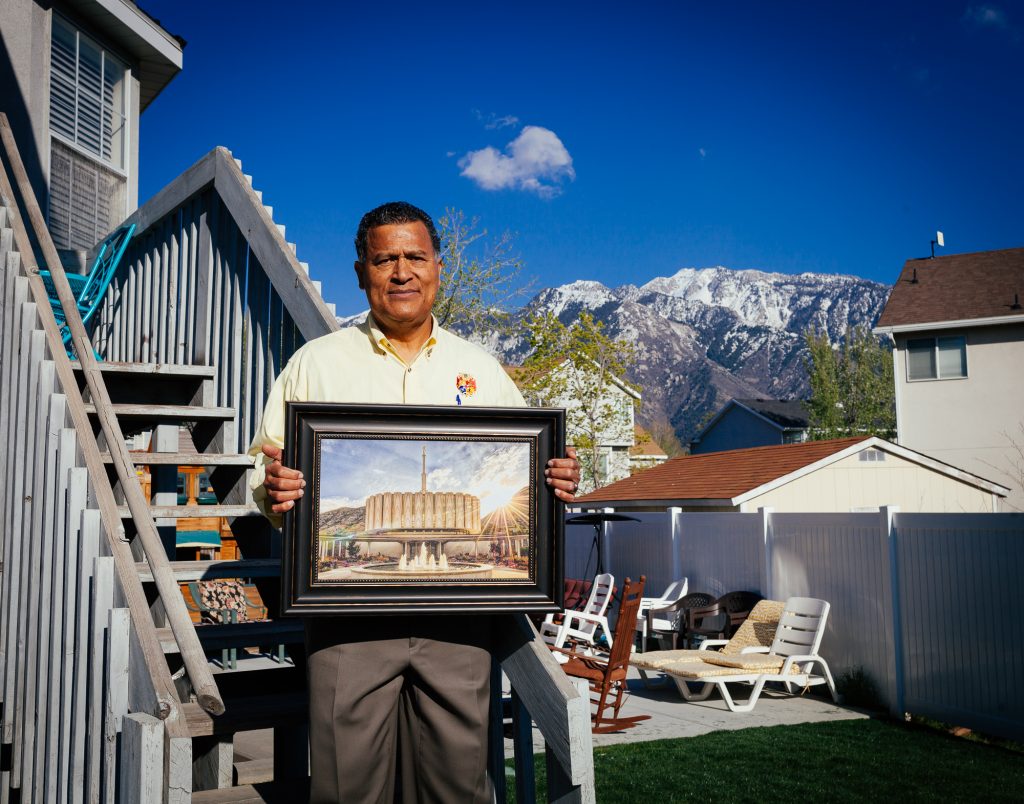

“I want to see all my children sealed in the temple of the church for this life and the next life. If we can all be sealed, we can all be together in the next life.”

Joel has never served a full-time mission with the LDS Church and dreams of doing one someday with Cindy.

Respect

Joel likes the respect that Tongans have for one another. Whenever you see a Tongan, whether you know them or not, you greet them. The typical expression of greeting is Mālō e lelei! (Thank you for being good). Joel continues to try to be a good person for his family and community in Utah.

“Your attitude about things will take you where you want to be. I’ve always been positive and don’t like to be around people who are negative.”

#FINDINGAMERICAN

To receive updates on the book release and exhibition of “Finding American: Stories of Immigration from all 50 States” please subscribe here. This project is a labor of love and passion. If you would like to support its continuation, it would be greatly appreciated!

© Photos and text by Colin Boyd Shafer | Edited by Kate Kamo McHugh. Quotes are edited for clarity and brevity.