Faded Memories

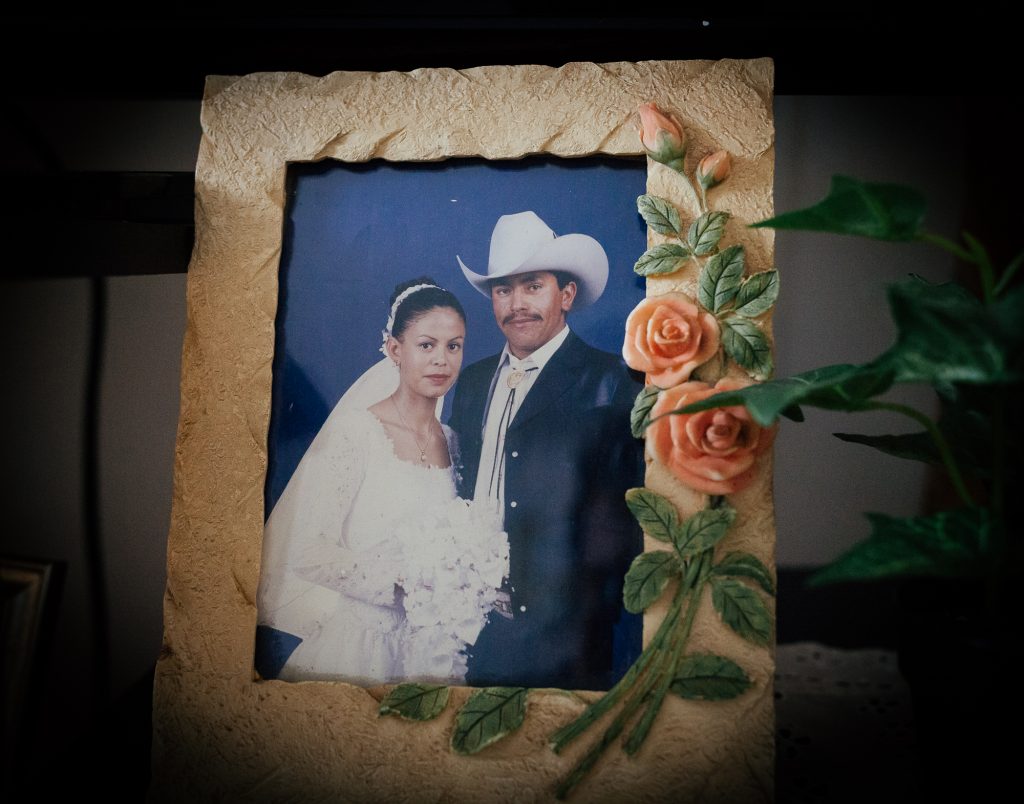

When Carlos thinks of the Dominican Republic, memories of “hectic traffic” and “warmth with a cool breeze” come to mind. It’s been almost two decades since he was last there, so his memories have faded. Carlos, the middle child of three, had a comfortable life in Santo Domingo, the capital. His father worked as a civil engineer for a successful company, allowing his mother to stay home to care for the family.

“I don’t have many things left that belonged to my dad, which is largely why I value his graduation ring so much. The ring is symbolic of the type of man that he was. He was kind, hardworking, and responsible. Those are ideals I try to live by.”

Tragedy

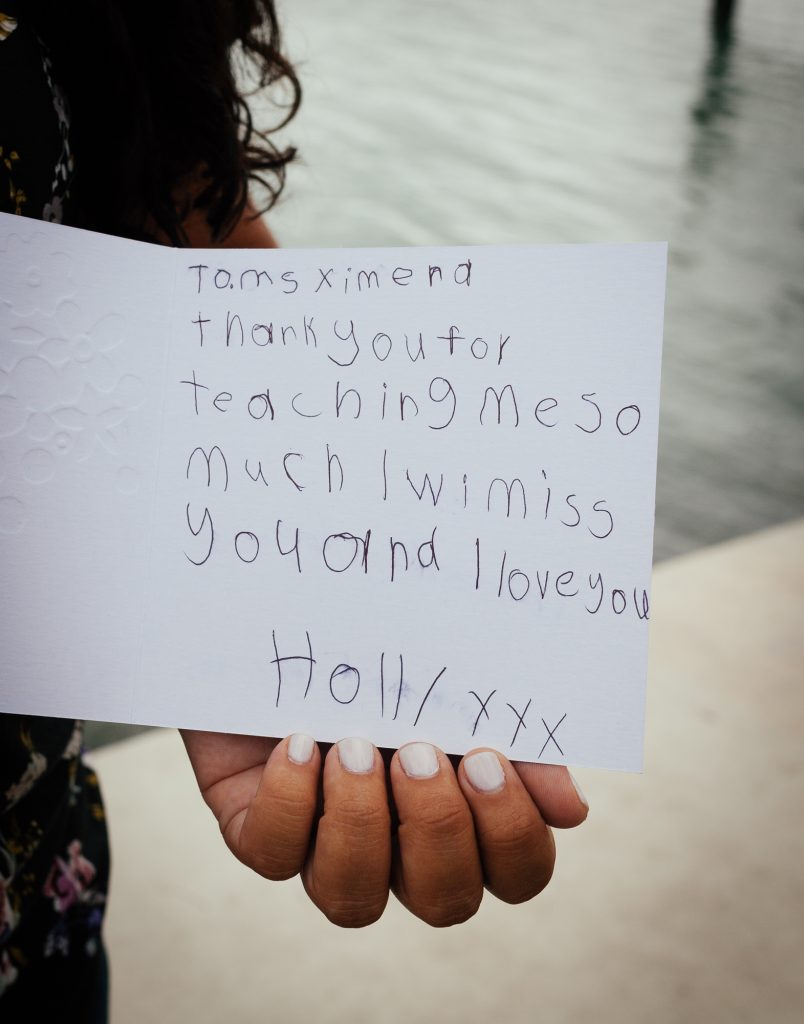

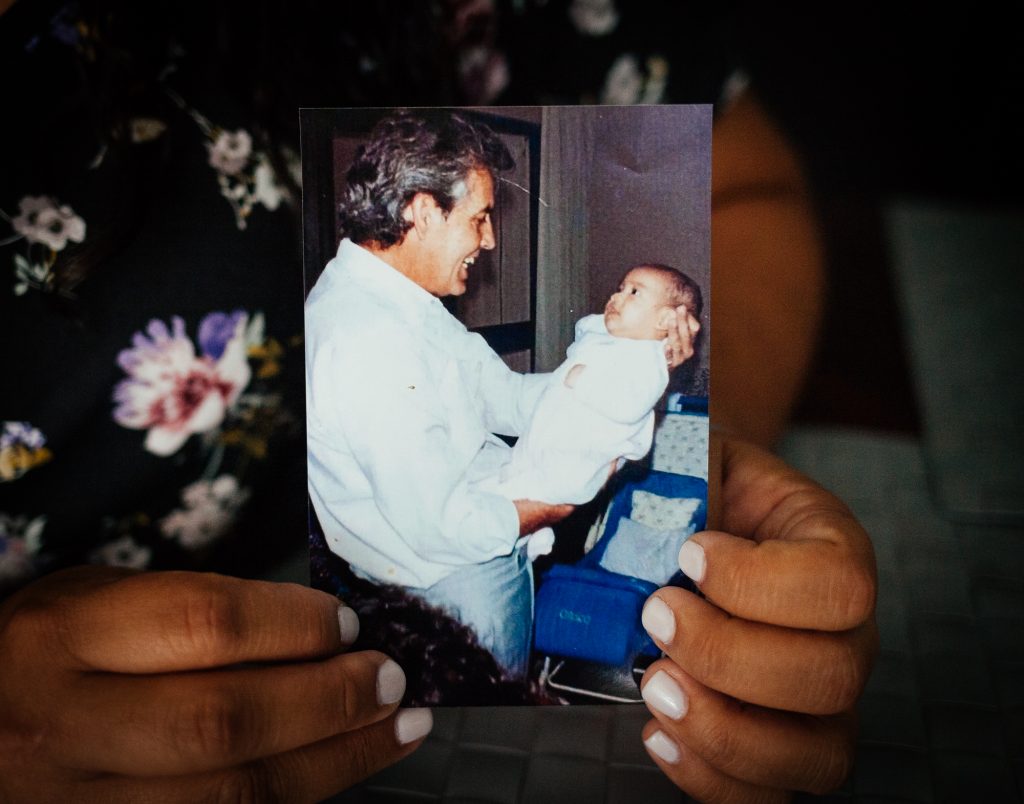

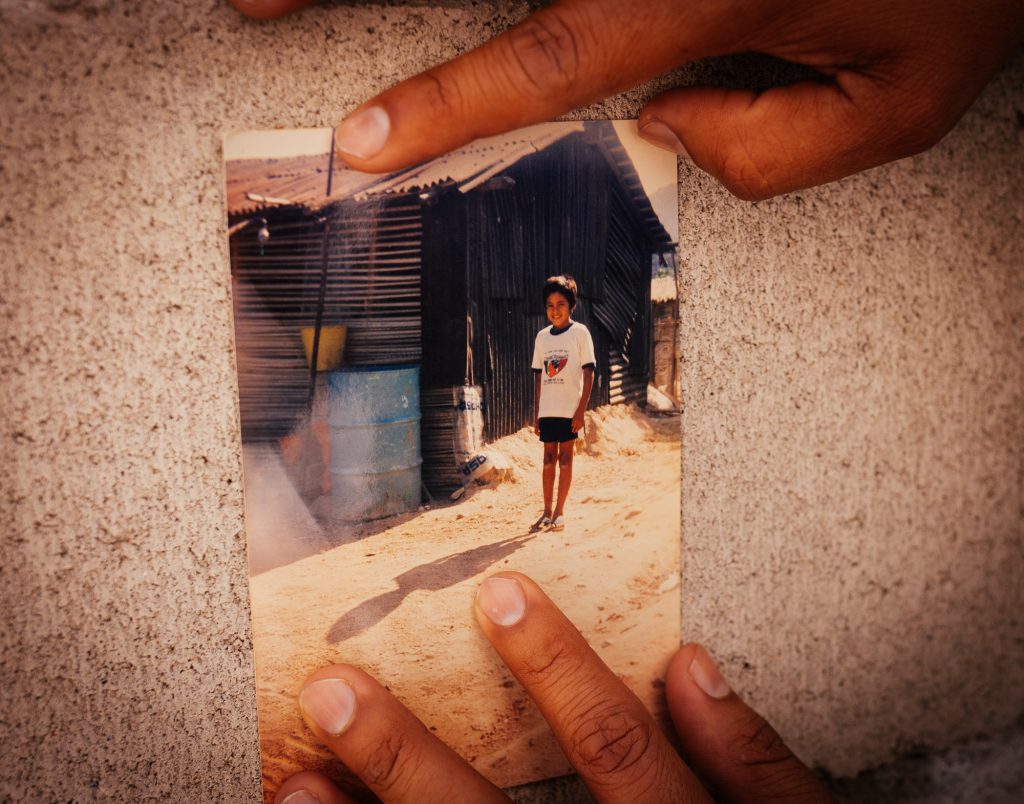

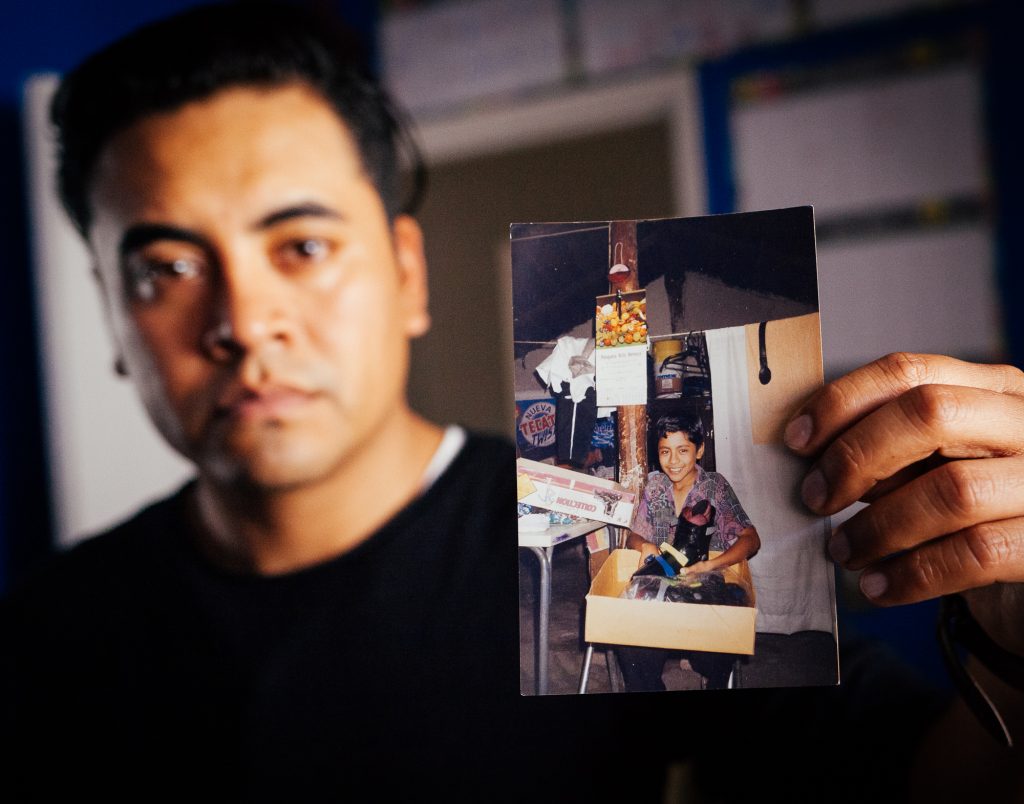

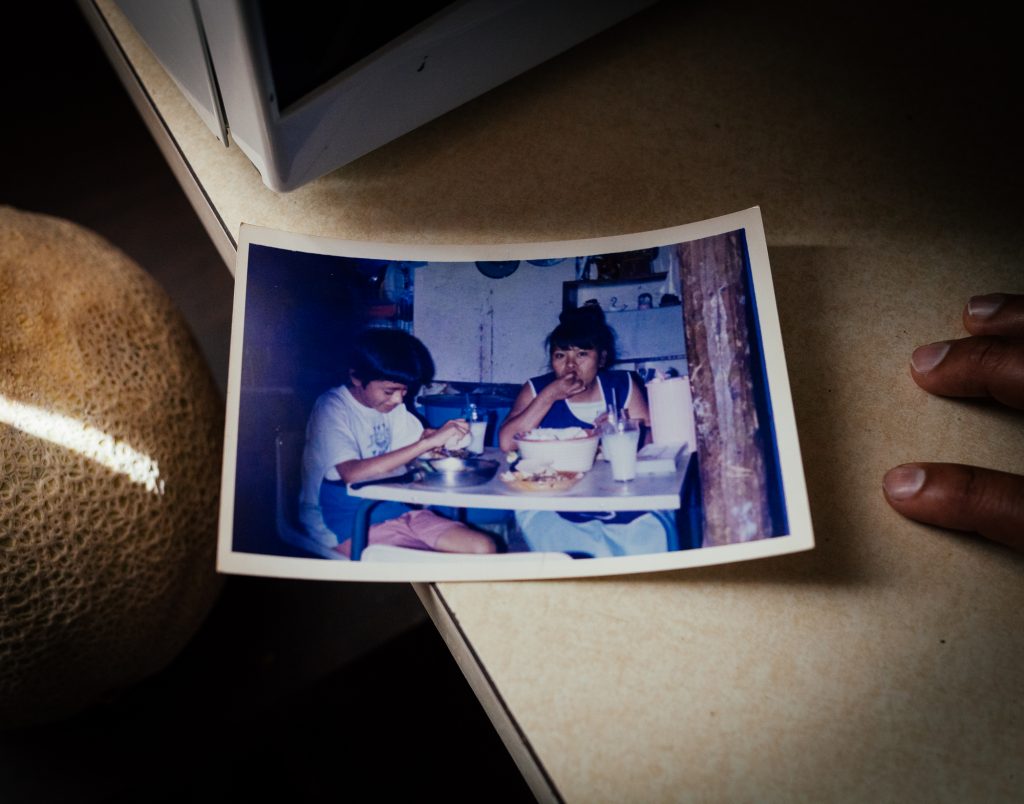

Carlos’s life changed drastically at eight years old when his father suddenly passed away from cancer. Carlos doesn’t have many photos of his time in the Dominican Republic. Most were left behind and then destroyed by bad weather. “I cherish the few photos that I have left.”

“This was taken at my first birthday party [see the above photo]. Obviously, I don’t remember that day, but I love the photo because of my father’s expression. I feel how proud he was of me just for being his son. It means a lot.” (audio below)

Up until age eight, Carlos was never an earnest student, mainly because of the family’s “comfortable lifestyle”. After his father passed away, he saw how his mother – who didn’t have a college-level education – struggled to pay their bills.

“Education felt like the only way I could regain that sense of security, so I began to take my studies very seriously.”

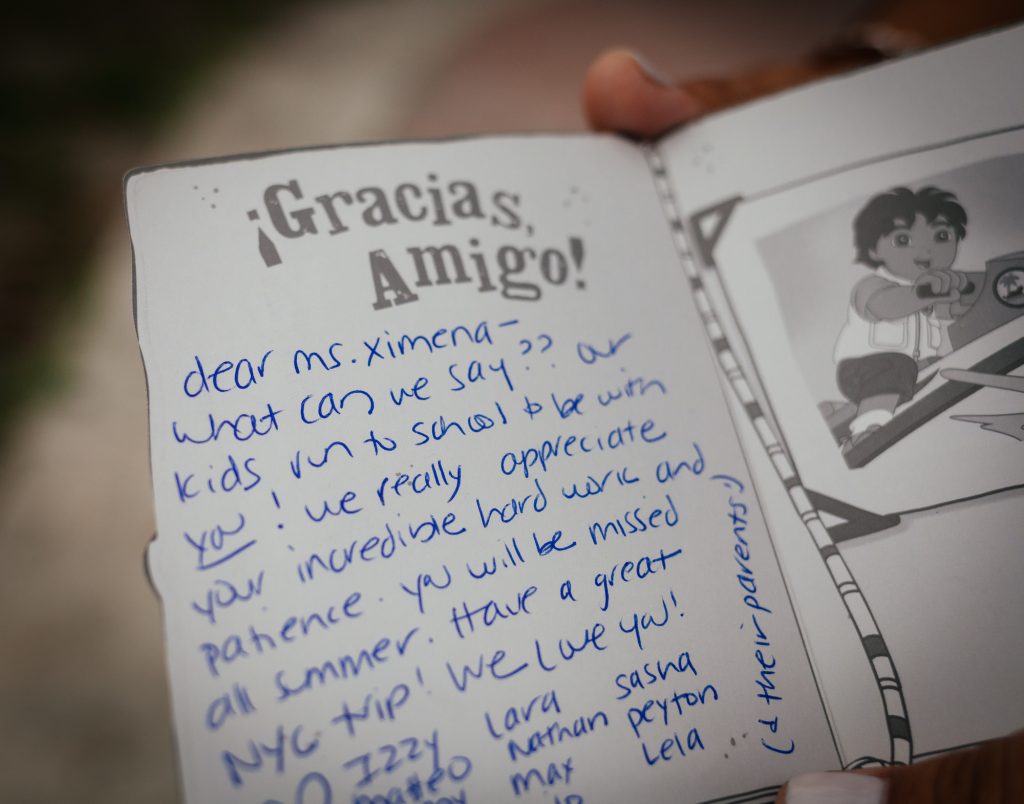

Thanks to a great third-grade teacher who helped and guided him, Carlos earned a medal for academic excellence.

“That year was the first time I was recognized as a good student. Winning that medal showed me that I was capable of doing well in school, which gave me a lot of confidence.” (audio below)

United States

Little by little, Carlos’s mom sold everything they owned, trying to gather enough money to pay for plane tickets for her, Carlos, and his two sisters, to immigrate to the US. Carlos remembers seeing their house empty. The day before leaving the Dominican, there was a power outage, and it was boiling hot. Carlos remembers how his mom spent the entire night, fanning him and his sister with a piece of paper. Carlos’s godparents dropped them off at the airport – Carlos, age 11, his mom and older and younger sisters.

It was the summertime in Pennsylvania when they landed in 2002, but to Carlos, it felt “super cold.” He was shocked to see his uncle, who picked them up at the airport, wearing a tank top. Carlos started school that fall in the sixth grade in Reading, Pennsylvania, where they would live for two years before moving to Lancaster.

First Day of School

“I remember walking into my classroom on the first day of school and feeling tremendous pressure to do well academically. I was aware of the sacrifices my mom had made to move to the US, all so that my sisters and I could have access to a better education and lifestyle.”

The other ESL (English as a Second Language) students in his class seemed to know some English already. Voices surrounded him, but he couldn’t understand what they were saying.

“It really hit me at that moment how far behind I was from my peers. The hurdles I would have to go through to learn felt overwhelming, and I just broke down and cried. The teachers had to kick me out of the classroom because I was so loud.” (audio below)

Carlos spent the rest of his first day at school in the main office. Over time, however, he began to adapt. Carlos knew learning English was the key to getting into college. By eighth grade, Carlos had not only learned the English language but was thriving. Within three years of arriving, this school in America named him their “Student of the Year.”

“This plaque [see the above photo] means so much to me because I know how hard I had to work to get it. I was focused on school and improving myself because I knew that was the only way I was going to get an opportunity to go to college. It felt like a culmination of one arduous journey and the beginning of another one.” (audio below)

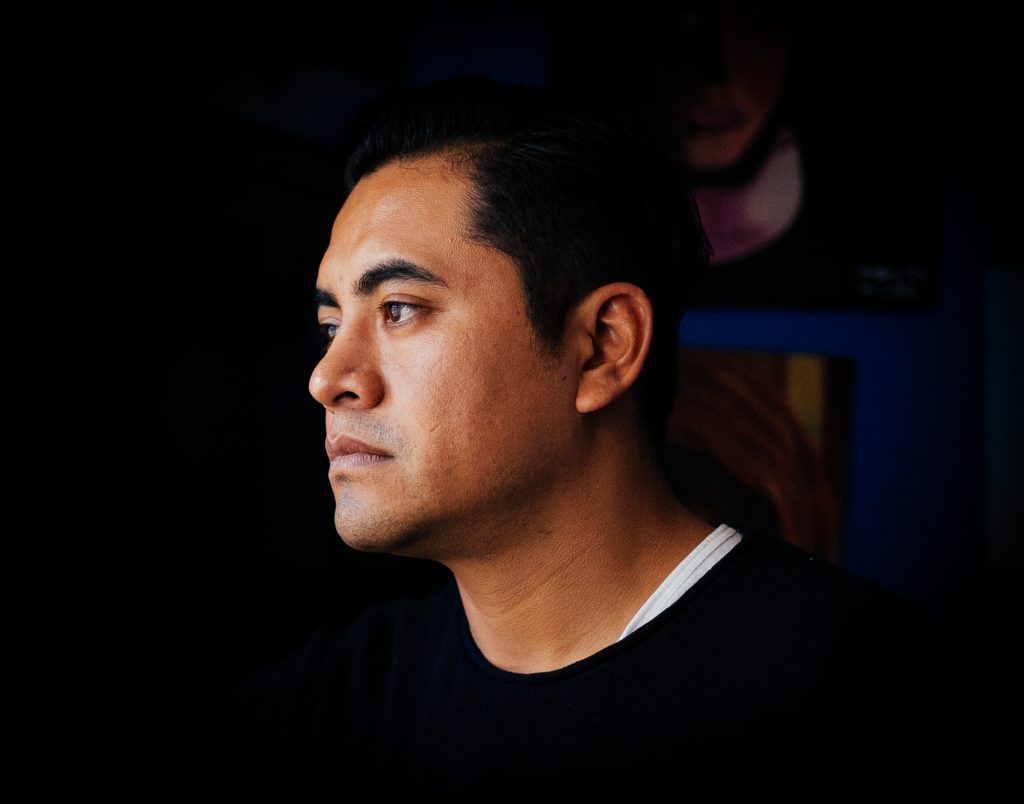

Undocumented

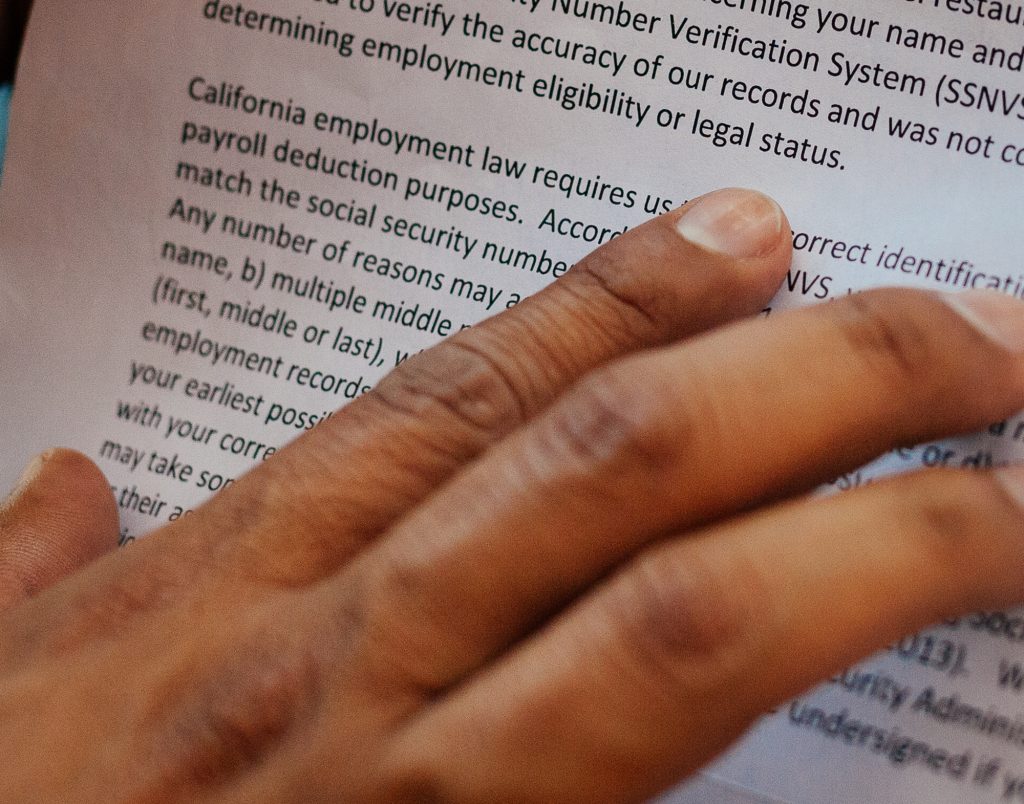

Carlos knew that his mother never planned on them returning to the Dominican Republic. He also knew their visas were going to expire, leaving them undocumented.

“Growing up undocumented was a difficult and traumatic experience. I felt like I needed to shelter who I was from the world so that I didn’t reveal too much and put my family in jeopardy of deportation. It only takes one call to immigration or for the wrong person to know about our status, for all of our sacrifices to have been in vain.” (audio below)

Carlos deliberately avoided making many friends – he didn’t want to get too close to anyone because of his undocumented status. His life revolved around school and studying. He never let his status get in the way of his studies. However, when Carlos started applying to colleges, the box where they ask for your social security number became an insurmountable problem. He decided to tell a high school teacher he trusted about his status.

“I was terrified to tell him. I feared his reaction because of the negative connotations attached to being undocumented. Some label you ‘illegal’ and dehumanize you when they find out that part of who you are. To my surprise, he was very supportive, and we are still close friends.”

Rejection

Carlos’s goal was always to go to college. He didn’t care where he went; he just wanted to continue his education.

“Receiving a pile of rejection letters was very hard because I had done everything I thought I could do in high school. I believed in the idea that if you work hard, you can get somewhere. At that point in my life, it wasn’t that way. I had worked as hard as I could, but society was still telling me I had reached the end of the line.”

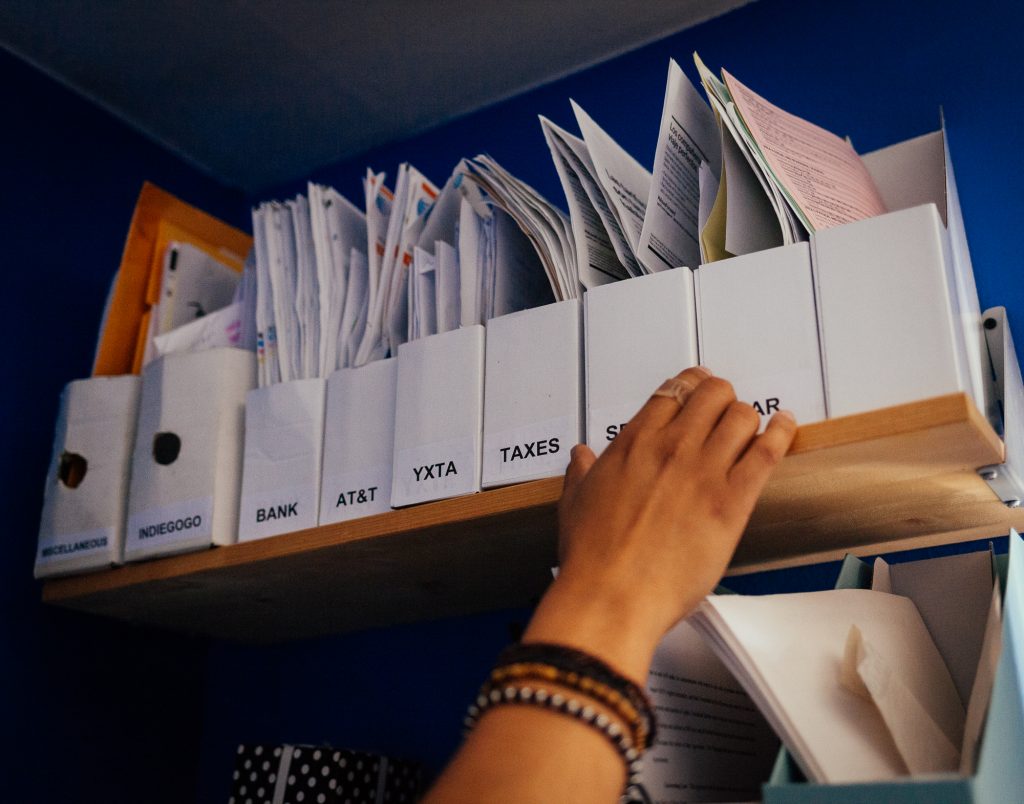

Although Carlos felt disappointed, he didn’t stop looking for options. Eventually, he found a local community college where he started studying social sciences in 2009. Carlos excelled academically and became a student leader – hoping that an opportunity would turn up. Because he was undocumented, he was paying the international student rate, so he had to work and study simultaneously.

The Quintessential Campus

In 2011 Carlos came across an opportunity to transfer to Amherst College in Massachusetts. He took the bus to visit the campus as he was too afraid to fly. Carlos fell in love with its “quintessential campus,” seeing it as the perfect learning environment. He majored in political science and interdisciplinary studies.

“After I got into college and learned about social justice and different issues, I realized it was important to tell my story and put a face to the undocumented community.” (audio below)

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) was announced in 2012 while Carlos was at Amherst. He applied, and in many ways, DACA changed his life.

Home

Carlos has always had an interest in politics – seeing it as a way to improve people’s lives. His college counselor at Amherst got Carlos interested in the idea of community organizing. He ended up moving to Chicago for a summer on an internship, where he learned firsthand how to mobilize communities. After graduating in 2014, Carlos returned to Chicago. He did more organizing work around raising the minimum wage for a project called “Raise the Wage.” He then headed to Washington DC to work as a congressional fellow for then-Congressman Mike Honda of California.

As an undocumented American, the last thing Carlos ever thought possible was spending an academic year in the United Kingdom, followed by a year in China. In 2015, Carlos earned a Gates Cambridge Scholarship to study for a master’s in Philosophy in Latin American studies in the United Kingdom. The following year he won a Schwarzman Scholarship to do a master’s in Global Affairs in China.

“I was humbled and empowered by my experiences abroad.”

Lancaster

In 2017, Carlos started working as the Statewide Capacity Building Coordinator for the Pennsylvania Immigration and Citizenship Coalition, which brings together immigrant and refugee rights organizations. Carlos works with partners in the community and helps them build their capacity to be better advocates.

Carlos describes this former US capital, Lancaster, as an increasingly Latino but traditionally Amish town. The Amish started the city’s “strong immigrant roots.” They came to Lancaster because of the religious freedom Quaker William Penn, founder of the English North American colony the Province of Pennsylvania, offered settlers. Carlos sees the city’s high per capita population of resettled refugees as being in line with Lancaster’s history of being welcoming to newcomers.

Solidarity

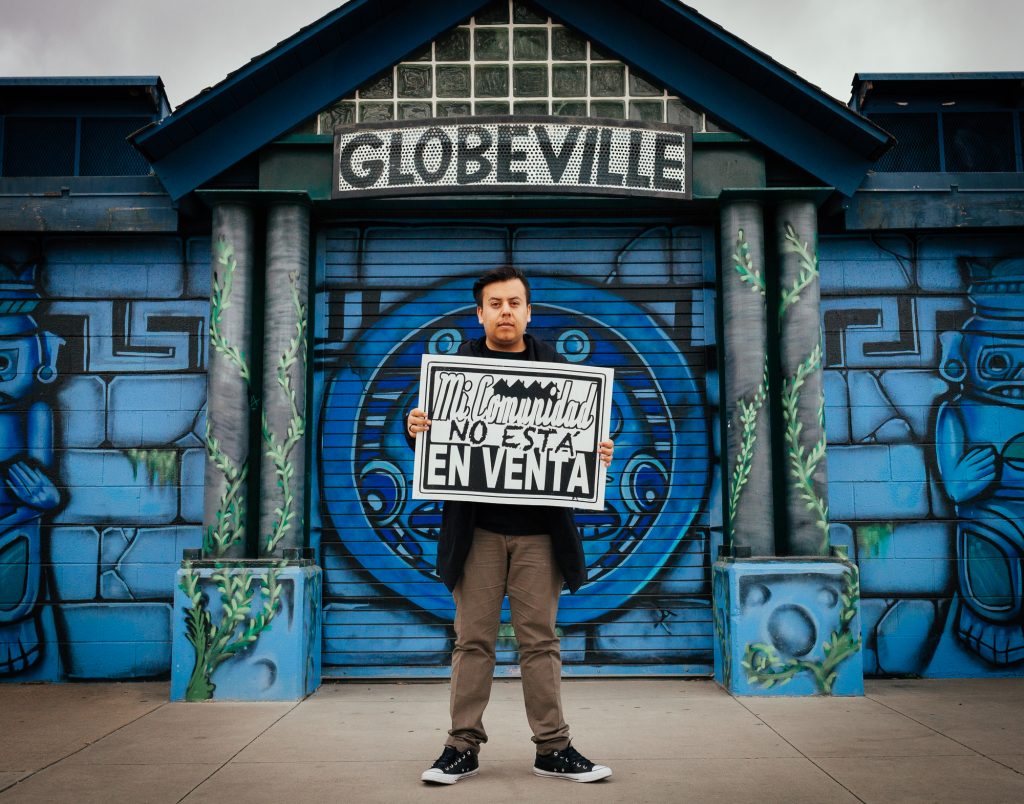

Carlos thinks it’s essential for more people who are undocumented to share their stories. He believes most Americans who haven’t met an undocumented person (or at least aren’t aware of meeting one), regard them in a negative light – as if they are faceless and nameless.

“We can be your neighbors or go to school with you or be your colleagues. Hearing our stories puts a human touch to the experience and builds solidarity. People who might be opposed or hostile to the undocumented community, change once they realize they know one of us. It’s important, especially in this political climate, that we tell our stories.” (audio below)

Identity

Regarding his place in the United States, Carlos does feel “in limbo.” His main document is his Dominican Passport, but he has spent most of his life in America.

“I stay connected to my Dominican roots through food, language, and dancing.”

Carlos thinks it’s funny when people ask him for recommendations when they travel to the Dominican Republic. “Don’t you realize I’ve been in the US for the last 15 years!” (audio below)

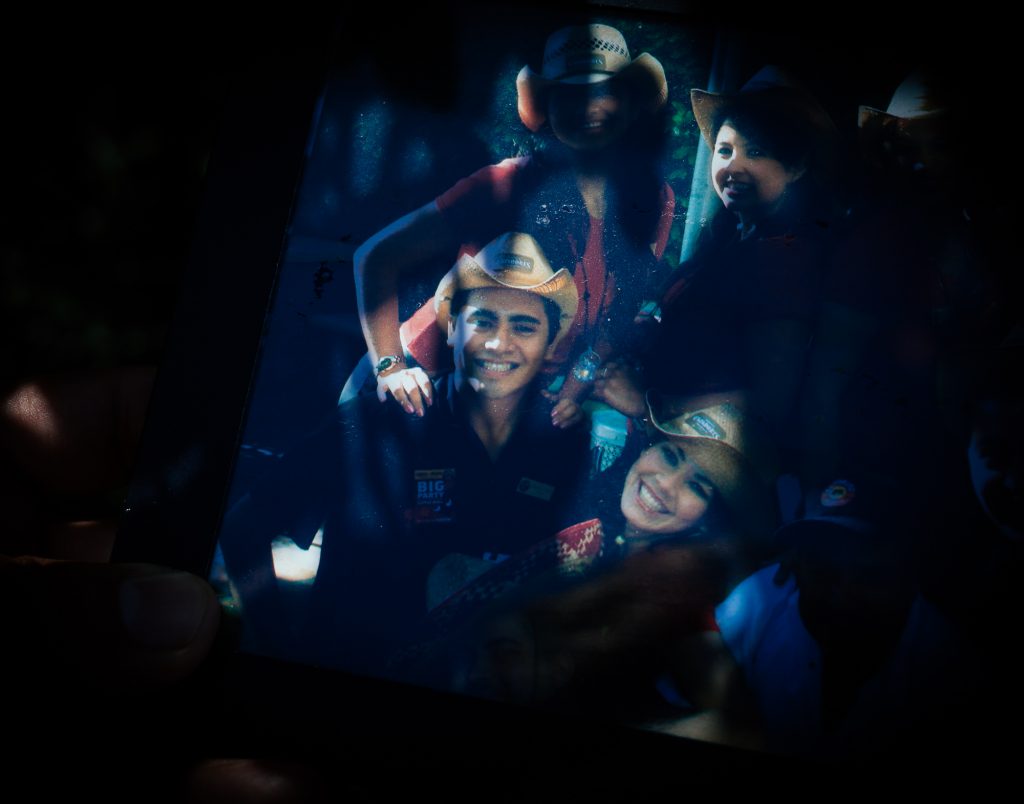

A Mother’s Love

Carlos will never forget that his mom sacrificed her own dreams and health so he could grow up in the United States and have better opportunities. Since coming to the US, she has done so many different jobs, from working at the trash processing plant to labor-intensive factory jobs. Today his mom has arthritis directly related to her work, but he has never heard her complain. Carlos knows he couldn’t do the work she does. His mom, and people like her, are his motivation. She came here with nothing, risked it all, knowing that her future wouldn’t be comfortable.

“My mom knew she was going to be undocumented and what that meant, but that didn’t stop her. She was chasing the possibility that things could be better for her children. I think that her sacrifices are inherently American. The immigrants who came to America took the chance to come across the ocean and didn’t know that things would be the best. I hope she has the opportunity to stay in the country legally, get out of the shadows, and pursue her passions.” (audio below)

Dreams

Carlos’s dream is to have the ability to plan his future freely. He doesn’t want his immigration status to be hanging over his head for life. He wants to be able to pursue his passions – public service and seeing the world. Carlos’s options are limited, but that’s something he has grown used to – finding a path despite limited opportunities. He knows many in his community are much worse off than he is.

“I’ve been fortunate that so far, my status hasn’t held me back that much – but it has for many people, and that’s what motivates me to continue to do the work I do.”

American Values

Carlos is hurt by people who advocate for an immigration system that would only allow people with extraordinary qualifications to immigrate to the US. He wishes the immigration system was more reflective of American values and traditions since the current system would exclude the ancestors of most Americans from coming here today.

“I want them to think about their own ancestors and the fact that most of their ancestors would not be able to come here if those were the standards. When they are advocating for that, they are slapping their ancestors in the face. I wish there was a system of legal immigration where there are different ways that people can come here and contribute, which is not what we have now.” (audio below)

*Update: Carlos is currently pursuing a joint degree in law and public policy at Harvard University with support from the Paul and Daisy Soros Fellowship for New Americans.

#FINDINGAMERICAN

To receive updates on the book release and exhibition of “Finding American: Stories of Immigration from all 50 States” please subscribe here. This project is a labor of love and passion. If you would like to support its continuation, it would be greatly appreciated!

© Photos and text by Colin Boyd Shafer | Edited by Kate Kamo McHugh. Quotes edited for clarity and brevity.