Childhood

Jazmin was born in Paracho de Verduzco, a small city in Michoacán, the same place her father was born. When she was only a few months old, they moved to Tijuana, and at a year old, her parents separated. Jazmin went to Cherán, her mother’s hometown.

When Jazmin was four, her father, who was living in the US, asked her mom if she would bring Jazmin and join him there.

United States

Jazmin’s memory of going to the US in 1996 as a four-year-old, is vague. She was in the car with her mother, her aunt, and her five-year-old cousin. She remembers commenting to her cousin on the lights as they drove north – it was the first time she had seen city lights like that.

“I thought the lights were all candles. My cousin said, ‘no dummy those aren’t candles, those are matches!’” (audio below)

They didn’t make it to the US on the first try. Their car was stopped at the Texas border and they were put in a detention center. After being returned to Mexico and released, they tried to cross the border again, and this time they made it.

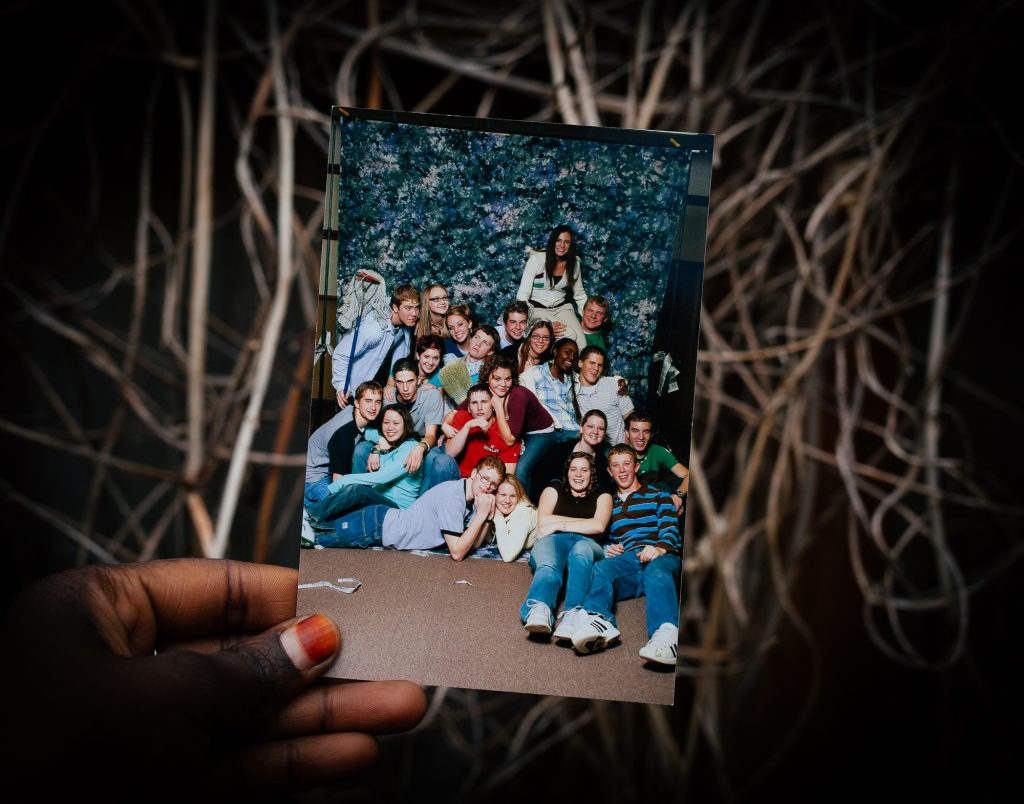

Their first stop was Henderson, North Carolina, where Jazmin’s father, uncle, and grandfather were working in the tobacco fields [see the photo below]. After a week, the family moved on to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Jazmin felt incredibly discouraged as a teenager in Philadelphia. She ended up dropping out of high school at the end of freshman year.

“I dropped out because I felt like I didn’t belong here. All my friends were getting their driver’s licenses and hoping to go to college. When I started the process, they asked for a social security number, which I thought I had, but I didn’t. I didn’t understand the meaning of being undocumented until I was in high school and needed that SSN.”

Return to Mexico

Jazmin didn’t want to be in school if she couldn’t go to college. After dropping out at 15, she started working full time as a server in a Vietnamese restaurant. Jazmin heard that her uncle was leaving for Mexico, and she told her mom that she was going to go with him – Jazmin thought she could start going to school again in Mexico. Her mom broke down in tears as she didn’t want Jazmin to leave her. In the end, she decided to go with Jazmin, and they moved back to Mexico together in 2008.

Jazmin started high school in Mexico, but she was finding it hard to pay for everything: uniform, textbooks, rent, food, etc. At first, Jazmin’s mom tried to help with the bills by selling tacos but after a few months, she returned to the US. After her mom left, Jazmin ended up dropping out of school again. She couldn’t see a future for herself in Mexico.

Immigrating… Again

Jazmin decided to try and return to the US in 2011 at 18 years of age and eight months pregnant. The only person who knew she was pregnant at the time was her father.

Even though it was a risk to her and her baby’s life, Jazmin thought it was worth it for her daughter’s future.

“I didn’t want my daughter going through what I went through and I would have risked everything to get her to be a US citizen and not have to jump borders like I was. I want her to have the opportunities that I didn’t.” (audio below)

Jazmin took the bus to the border and called her dad. She hadn’t told him her plan ahead of time, and he was surprised to hear that she was going to cross. The next time she called him, Jazmin was being held hostage.

Hostage

While waiting at the bus station with her “coyote” (the person she hired to help her cross the border) two trucks suddenly pulled up and told them to get in. The men were part of an armed cartel – Jazmin could see weapons and blood in the truck. They took her coyote’s phone, but Jazmin hid hers and managed to text her dad. They brought her to a payphone and made her call her dad. The cartel told him they wanted five thousand dollars each for her and her coyote, or else they would kill them. Her father told the cartel he didn’t have much money, and eventually, they said they would take $1500 and would help Jazmin cross to the US. Her dad deposited the money. (audio below)

For two weeks, Jazmin waited in a small one-room wooden house packed with other people waiting to cross. They tried twice to take Jazmin to the river to cross, but each time there were flashing lights on the other side. On the third attempt, they put Jazmin and another pregnant woman in inflatable donuts and pulled them across. She thought she was going to drown. On the other side, they walked for three hours, then they were told to run to a car that was supposed to be waiting for them once they reached the road; instead, the immigration authorities were there.

Kindness

Jazmin remembers the immigration officer asking for her name. He could see she was pregnant. She told him everything: how she had lived most of her life in the US, then left for Mexico, and was now trying to return for her daughter’s future. Jazmin knows he could have deported her right away, but he didn’t. He asked her if she wanted to see a judge, and she said, “no.” Now that Jazmin understands more about immigration law, she knows that if she had seen a judge, she could have asked for asylum based on all that has happened to her.

“Instead of deporting me, the officer gave me an ‘involuntary departure.’ He took me back to Mexico and dropped me off at a bus station. Instead of just telling me to go by myself, he crossed with me to make sure I was going to be okay.” (audio below)

The Boat

She called her dad from the bus station in Tamaulipas – worried, he asked her what she wanted to do next. She told him she would stay in Mexico. After the conversation, while at the bus station, she met a guy who seemed trustworthy, explained her situation, and he said he could help her cross to the US with his boat.

The next morning Jazmin told this stranger that she wanted his help. Within 15 minutes, she was in Texas. She got off the boat and ran to the nearest house. The person in the house brought her to a gas station and told her, “good luck.” She called her dad from the payphone, and he had her aunt, who lives in Texas, go pick her up. (audio below)

Jazmin stayed in Texas for two weeks with her aunt – eight months pregnant, and exhausted. She could either stay and have the baby in Texas or go with her father by car to Philadelphia. Jazmin decided to go.

She remembers the checkpoint on their way north, and the officer commenting on her being pregnant. Jazmin thought they were going to ask her for an ID or papers, but they didn’t. Her pregnancy was enough of a distraction. Three days after getting to Philadelphia, Jazmin gave birth.

Education

Jazmin told her mom that she wanted to find a job and try going back to school. That year she attended three different high schools. The last school had an accelerated program, and Jazmin was able to finish all of her four years of high school in only two. After applying and receiving DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) in 2013, Jazmin started attending Esperanza College for a degree in criminal justice. She managed to afford college by getting an international scholarship, working a part-time job, as well as living with her mother rent-free.

On top of the financial challenges, her father, who is an alcoholic, started drinking a lot. This forced Jazmin and her daughter to move in with an aunt who was kind enough to let her stay and eat rent-free. She knows she couldn’t have graduated without her family’s support.

Jazmin went on to pursue a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice and graduated in 2016.

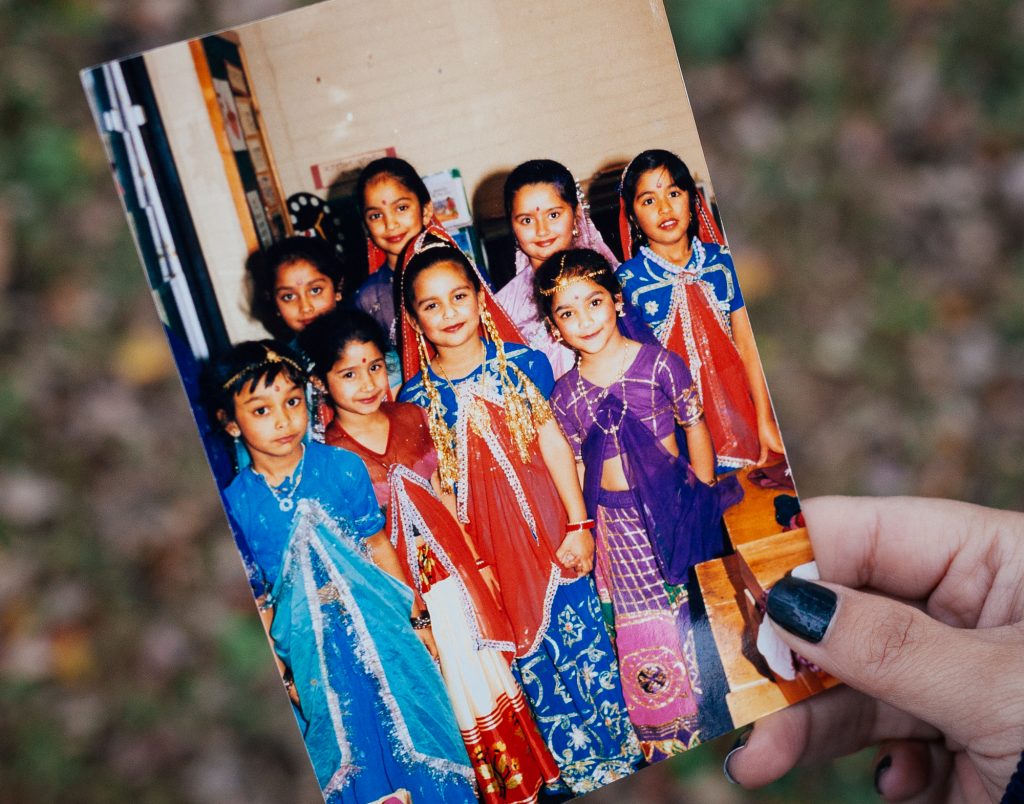

“This is my college graduation hat [see the photo below], dedicated to our traditional dance, ‘Danza de los Viejitos’. On it, I wrote: ‘Fly as high as you can without forgetting where you come from’. It’s something we all should keep in mind. We can’t forget our roots because that’s what led us to be who we are now.” (audio below)

Inspiration

Jazmin was 18 when she had her daughter. Jazmin’s mom, who didn’t know about her daughter’s pregnancy, was pregnant at the same time that she was. Jazmin’s mother gave birth three months before she did, so Jazmin’s sister and her daughter have grown up like twins.

“I always dressed them alike, treated them alike, and they grew up like sisters even though one is an aunt, and one is a niece.” (audio below)

Everything that Jazmin does is with her daughter and sister in mind. She wants them to see a positive example of what they should and can do. Jazmin didn’t grow up with a role model who went to college, let alone finish high school, and she loves that her daughter, siblings, and cousins can look up to her and see that going to college is an option.

In many ways, Jazmin thinks having a daughter as a teenager, gave her the motivation to keep going and be the best possible version of herself. If she hadn’t had that responsibility early on in her life, she thinks she may be working at a factory or even an alcoholic like her father. (audio below)

Jazmin remembers when she felt out of place in school because the other kids’ parents were professionals. She was the only one who didn’t want to say where her mom worked because she was a cleaner. She thought the other kids would look down on her family. Now that she is an adult, she recognizes how hard her mother was working to provide for her. (audio below)

La Muerte

Jazmin says that trying to cross the border is like playing with “la muerte”.

“The border is something indescribable. It’s a place that’s not for humans. It’s like a game – I usually compare it to playing cat and mouse. The immigrants are the mice. The cats are playing to trap the mouse.”

She wants people to know that immigrants aren’t coming to the US to take anything from Americans. She also wishes most Americans would reflect on the fact that their ancestors came from somewhere else at some point.

“The US is where everybody seeks their dreams – “American dreams” – so why aren’t immigrants accepted? You never know what they’ve gone through. At the end of the day, everybody is working. I’ve been reporting taxes, so I’m not stealing from anyone – I’m actually giving back. We would just like to be accepted.” (audio below)

Philly

Jazmin likes living in Philadelphia now, and truly believes it is the “city of brotherly love.” She feels like it’s a friendly place where other cultures are appreciated. As an example, on October 4th she was outside her home, dressed in traditional clothing and cooking for the Patron Feast. The neighbors came over because they were curious and wanted to know more about what she was celebrating. Jazmin appreciated that they took an interest, and feels like this kindness is symbolic of the city.

Pride

Jazmin works at a law office as a senior paralegal. In 2017, she was the first Latino and first DACA recipient to receive the HIAS “Golden Door Award” for the legal services she has provided to Philadelphia’s immigrant community. Jazmin is determined to go to law school and get her Juris Doctor degree.

“Law is my passion and I’m not going to give up my passion just because I don’t have papers. That’s not a good reason to stop. If we are already here, we might as well prove to the US that we are here and contributing and can help.”

Jazmin hopes her daughter tell her friends at school proudly, “my mom works at an attorney’s office.”

*Update: Since the interview, Jazmin was able to obtain a T visa (a visa for certain victims of human trafficking and immediate family members to remain and work temporarily in the United States). She also gave birth to her second daughter and is waiting on the birth of her first son.

#FINDINGAMERICAN

To receive updates on the book release and exhibition of “Finding American: Stories of Immigration from all 50 States” please subscribe here. This project is a labor of love and passion. If you would like to support its continuation, it would be greatly appreciated!

© Photos and text by Colin Boyd Shafer | Edited by Kate Kamo McHugh. Quotes edited for clarity and brevity.