Childhood

In 1992, Isaías [who prefers the pronoun ‘they’] was born in Guadalupe de Trujillo – a tiny town of 400 people at the foot of mountains in Fresnillo, Zacatecas. Isaías’s elementary school was small, and because they didn’t have enough teachers, the students would either attend at night or in the morning. Isaías remembers being incredibly poor, often being alone, and bicycling a lot – up into the mountain as far as possible.

Isaías’s mom remembers her child as being unique, strong, and intelligent while growing up.

“He could have conversations like an adult when he was a little boy.”

Isaías’s father’s family had long been working on a big ranch nearby, which is how they all ended up in Guadalupe De Trujillo. Their family grew corn, beans, chile, and other produce to subsist. Over the years, the family’s financial resources steadily depleted as they couldn’t compete with cheaper imported corn from the USA as a result of NAFTA. They could no longer survive there.

“It was tough to live. Agriculture wasn’t good, and we were not making enough money to survive.” (audio below)

Family History

Isaías’s family has a long history of coming to the United States. Their maternal grandfather was a bracero (temporary farm worker) in the 1960s. He would go north, work the fields, and then return to Mexico. It was much easier to cross the border at that time. His sons did the same when they were old enough. Isaías’s two older brothers were inspired to try their luck in the US like generations before them. Isaias’s brothers moved to Colorado and started working in fast-food restaurants and later worked in drywall. The family was surviving on the remittances they were sending back to Mexico.

Isaías’s older brothers encouraged their parents to visit them in Colorado. It was supposed to be a vacation – a spring break trip on a six-month visitor visa.

“We left everything as though we were going to return, but we never did.”

Valentine’s Day

At eight years old, Isaías and parents crossed the border at El Paso, Texas, during the night on Valentine’s Day, 2001. Isaías woke up on the way and remembers being fascinated by the structure of the houses – in particular, the angle on the rooftops designed for the snow. This was something not seen in Mexico and previously only seen on the miniature Christmas houses from childhood which Isaías received in exchange for Coca-Cola bottle caps.

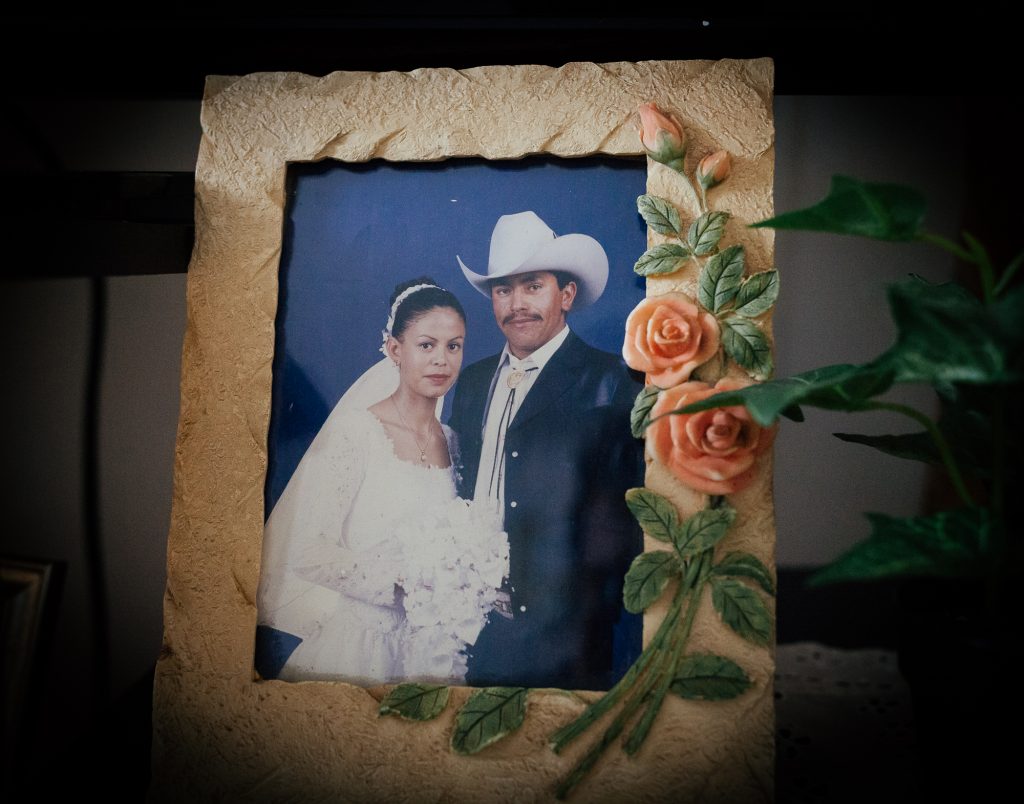

After arriving in the US, Isaías’s mom would make tamales to sell every Friday at the local liquor store. Isaías learned to work hard helping mom sell tamales. Isaías’s father [see the above photo] started working in road construction and has been doing this job for over 20 years now.

Adjusting

Shortly after arriving, Isaías started third grade.

“I was placed in a classroom where I didn’t understand anything. I would often get in trouble for not following the rules, but it was because I didn’t understand what I was supposed to be doing. My teacher, who was bilingual, told me that she didn’t speak to me in Spanish because she didn’t like Spanish. In 4th grade, I had a teacher who was Cuban, and she helped me realize that what I was going through when I got here was not normal.” (audio below)

It was challenging to adjust to being inside a house all the time. In Mexico, Isaías was always outside and free. In Colorado, Isaías wasn’t allowed to go out alone. Their mother didn’t think it was safe, as, at the time, there were a lot of gangs in their Globeville neighborhood.

“I was happy and excited because, in Mexico, we never celebrated birthdays since we were poor.”

Undocumented

Isaías always knew that the family was undocumented; their parents never hid it from the children. Isaías knew they couldn’t get a driver’s license or a social security number and that working legally wasn’t an option.

“In high school, I worked very hard, hoping that by the time I graduated, I could become ‘legal.’ When I got to senior year, I realized that it wasn’t happening – that began my activism. I did not have the resources at highschool. All of the conversations on how to go to college didn’t apply to me. Almost 50 % of my class was undocumented! I realized they needed help.” (audio below)

The realization that undocumented students were not being properly prepared for life after high school led Isaías to help form an advocacy organization called “Keeping The Dream Alive”.

Advocacy

Isaías graduated from high school in 2011. It was going to cost between three to six times more for them to go to college than a documented student – so Isaías didn’t go. Isaías began advocating for in-state tuition for undocumented students in Colorado, becoming more vocal and meeting with state representatives. In 2013, Colorado changed the policy, and undocumented students were eligible to pay in-state tuition fees. Isaías increasingly connected to people all around the country, fighting for causes related to undocumented youth.

Isaías feels like since the 1980s there has been a lot of promising talk by politicians with minimal action. Even with Obama, Isaías didn’t see their community getting enough support.

“Obama deported more of our family members than any other president in this country.”

Isaías started canvassing, signing up family members to vote, going on hunger strikes, and other non-violent protests such as ‘occupying.’

“I had nothing else to lose. I became very vocal about my story.”

DACA

Finally, in 2012 Obama passed the Dream Act. DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) allows undocumented people who arrived in the US as children to receive a renewable, two-year period of deferred deportation. After DACA came into effect, Isaías decided to take a step back from leading the community. As the face of many campaigns, assuming the role of “poster child” was a lot of pressure, and Isaías came to realize that it was all-consuming.

“I would get asked about my hobbies and I always said, ‘I don’t have a hobby; I organize.’ When I wasn’t doing that, I was resting.”

On August 15th, 2012, the day of the announcement that applications for DACA were open, the police pulled Isaías over for speeding. Isaías was heading home after the press conference – to gather paperwork to help at a DACA clinic. Isaías was not speeding.

Arrest

When asked for identification, Isaías showed a school and a church ID, which didn’t satisfy the officer. The police officer asked: “When did you come into the country? When did you learn to speak English?” Isaías refused to answer because these questions did not relate to the alleged speeding infraction. Told to get out of the car, Isaías went to text their partner. The police officer took Isaías’s phone and threw it. Then they arrested Isaías, along with Isaías’ partner, who had arrived on the scene. Luckily, the office of the non-profit “Rights for Our People” group was closeby, and the director came on the scene to help.

“The cop kept asking if I was ‘legal’.”

Isaías didn’t want to answer any questions unassociated with being pulled over. The officer said they were going to call ICE, which Isaías said was fine. Isaías told the officer, “when I get out of here, we are going to sit down and talk about how you aren’t supposed to be arresting people based on immigration status.”

“I wasn’t afraid I was just very angry. I told myself if I end up in a detention center, then I would organize in the detention center”.

A year after the arrest, as promised, Isaías did discuss this with the arresting officer and the chief of police, who after the discussion, committed to better training for police officers. (audio below)

Sister

Isaías’ older sister stayed in Mexico when they left in 2001 because she was already married. Isaías misses her constantly and says that she is the reason why their parents are physically in the US but mentally still in Mexico. It wasn’t until 2015, 14 years later, when the Mexican government facilitated a trip to Mexico for “prominent” activists and immigrant youth with DACA, that Isaías was able to finally see her again.

“It was the very first time I was able to travel back to Mexico, after 14 years, and hug my sister. Because of the current US immigration laws, I am no longer able to do that and don’t know when or if I will hug her again.”

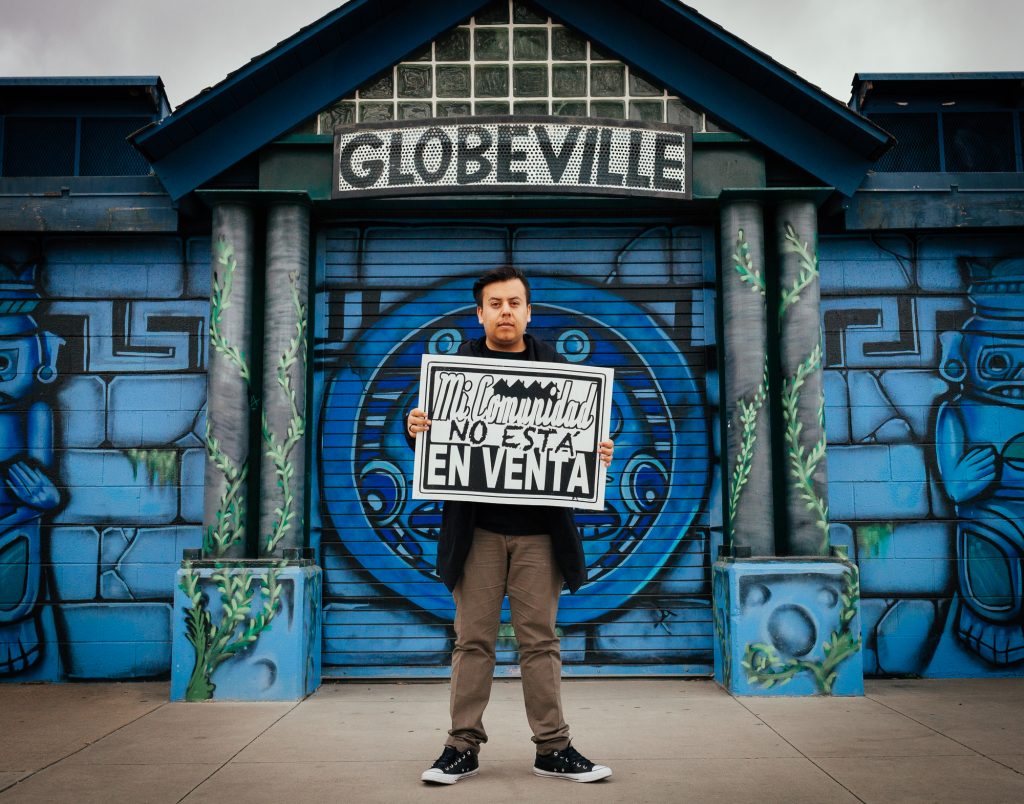

Globeville

Isaías has been living in the Denver neighborhood, Globeville, since arriving in the states. Globeville used to be a separate little town outside of Denver, where European immigrants came to work in the coal smelting plants. The houses are small – built as temporary housing for the workers, and many of them have weird shapes because residents have added on additions. Isaías highlights how 80216, their zip code, is one of the most polluted in the country because of the smelting plants. As a child, Isaías remembers the city removing contaminated topsoil, house by house, throughout the neighborhood.

People referred to Globeville as “Little Guadalupe” when Isaías was young because the population had become predominantly Latino. Today Globeville is undergoing intense gentrification, and Isaías sees the harm that results firsthand.

“All the people that we knew are no longer here. The only people of color still here are ones that were able to buy a house, since rent has skyrocketed.”

The only reason Isaías’s family is still able to stay in Globeville is that the landlord hasn’t increased their rent in 10 years. However, the landlord has informed them that he will no longer be renting out the house. Isaías has an opportunity to buy the house, but it’s too much.

“My family is so attached to this neighborhood and this house. If we have to find a new place, we would rather go back to Mexico.”

Education

Isaías has been studying social work part-time and working at the front desk of a local charter high school. Isaías has been trying to transition into an advocacy role in schools. Through experience with organizing and advocacy, Isaías understands the importance of equal access and high-quality education for the next generation. (audio below)

“I get a lot of hope from working with students; they are hilarious.”

Queer

Isaías came out as queer in high school. (audio below)

“I was very proud of myself – coming out as both undocumented and queer.”

Isaías emphasizes how for many trans/queer immigrants who are undocumented, deportation could mean returning to a country where their security may be in jeopardy because of their sexuality or gender. A lot of Isaías advocacy has been at the intersection of trans/queer and immigration – bringing people together at this intersection instead of letting these two movements remain siloed. Isaías emphasizes how in the immigrants’ rights community, can be transphobic, and the LGBTIQ community can be anti-immigrant. (audio below)

Strong and Honest

Isaías describes their mother as the strongest and most honest person they know.

“I’m so thankful to mom. She was always very honest with everything we were going through including living in poverty. She has helped me by always being honest with myself and other people. Sometimes too honest. Sometimes I don’t feel comfortable being as honest as she is.”

While Isaías’s mom thinks life has been better for her kids in the United States, it has been harder for her and her husband. She is tired of how hard her husband’s job is on him.

“My future isn’t in the US, it is in Mexico. My main hope is to look after my kids, and I won’t be able to see them if I’m there. It is really sad. It would be hard to leave them.” (audio below)

Her dream is for Isaías to graduate from university. She understands how hard it is for Isaías to do that since they have to work to help support the family.

*Update: Since the time of the interview, Isaías has returned to community organizing for immigrant student rights, and to remove educational barriers for students of color. They are currently the Operations Manager & Executive Assistant for Padres & Jóvenes Unidos. Isaías’s family’s house was placed on the market, and they had to move out. The family was able to stay in Globeville but now they are paying four times more in monthly rent.

#FINDINGAMERICAN

To receive updates on the book release and exhibition of “Finding American: Stories of Immigration from all 50 States” please subscribe here. This project is a labor of love and passion. If you would like to support its continuation, it would be greatly appreciated!

© Photos and text by Colin Boyd Shafer | Edited by Janice May & Kate Kamo McHugh. Quotes edited for clarity and brevity.