Ihab is the son of a Jordanian father and an Iraqi mother. His paternal family – the Sadoons – have historically been bedouins distributed between Jordan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait. His father was an orphan, living in a society that did not welcome his people. Despite this, at age 18, Ihab’s father was accepted to study medicine at Johns Hopkins and Columbia University.

War

The family was living in Iraq when Ihab was born in 1979, because of the war and the country’s need for doctors. They would move from one place to another, depending on what hospital needed his father the most. For the first ten years of his life, he and his three siblings grew up surrounded by war.

“I remember our house was hit once with a bomb. I remember packing so many times – packing our stuff and going from one place to another. And I remember losing my friends. We didn’t live more than two or three years in one place – we kept moving, which was very frustrating – it just became so much harder for me to make friends. It’s not worth it to make friends, then lose them in a year or two. We had to leave so many places.” (audio below)

Dentistry

In the 1990s, the economy was failing in Iraq, so the family moved to Jordan, and that’s where Ihab attended university to become a dentist. In 2007 he was accepted to NYU’s graduate program in implant surgery. He did an internship in Maryland and a residency at Columbia University in NYC. Ihab planned on returning to the Middle East, but with the Arab Spring happening, and his daughter in the US, he decided to stay.

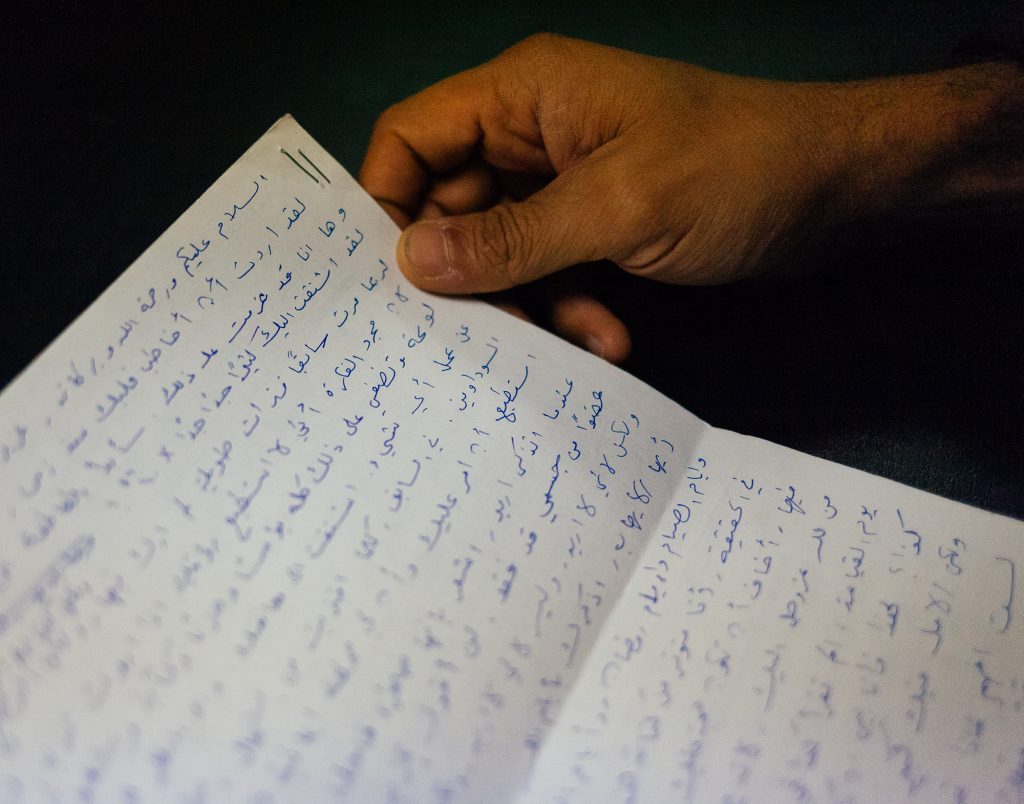

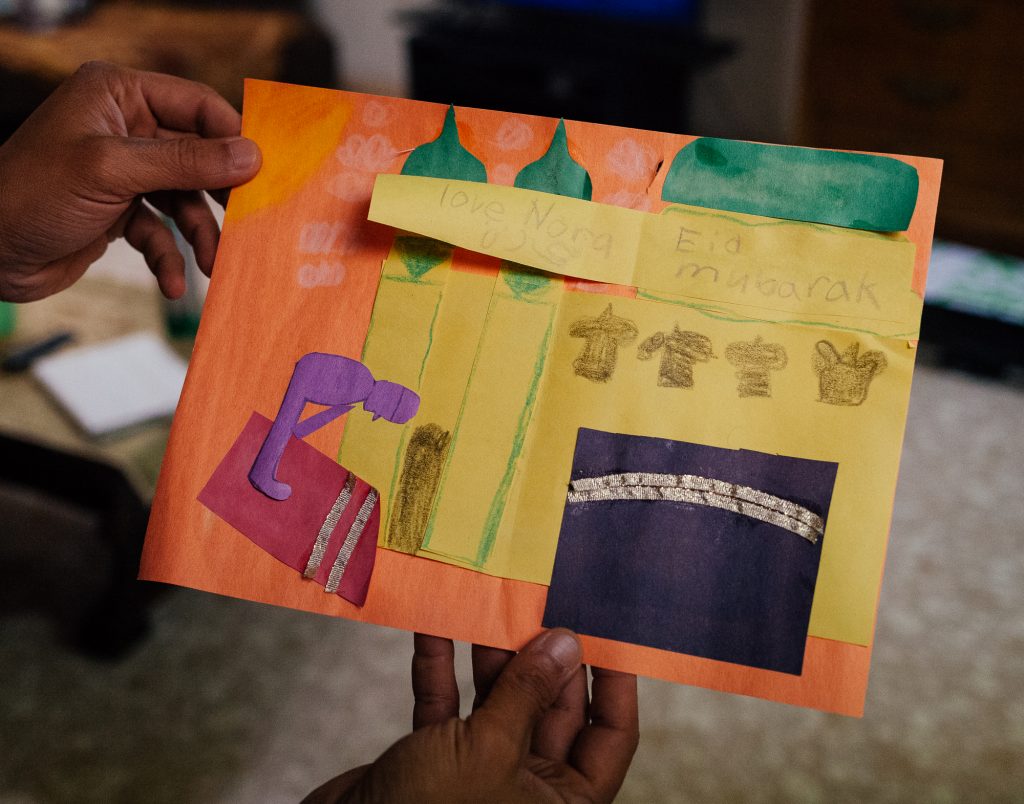

While away from his region of birth, Ihab keeps letters from his late father and his sister close to his heart.

“Every time I feel bad, I open these letters. I start reading and feel good. My dad always reminded me that I came here for a reason – ‘don’t waste your time; do not forget that there are lots of people that are waiting to be helped by you. Always be kind to others. Don’t forget me.’”

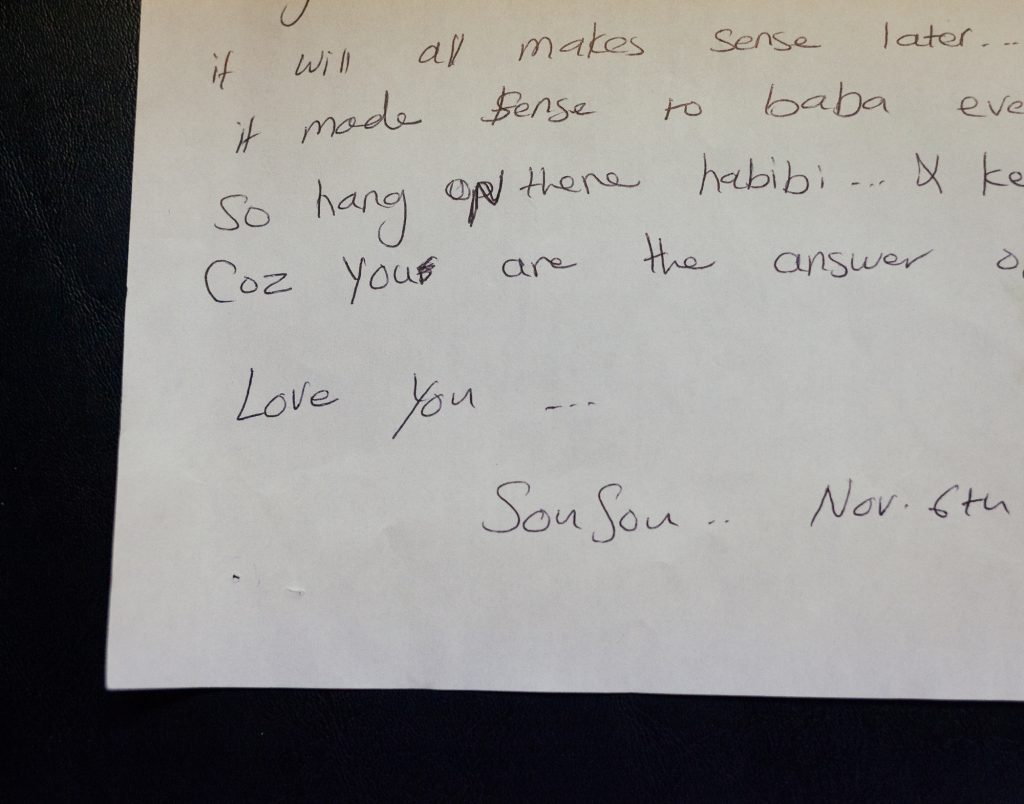

Other than his father, he has always been close to his younger sister. Ihab cherishes a letter she wrote saying how much she loves him and can’t wait to travel with him.

“I was having a tough time with my marriage, and my sister always tried to say positive things and remind me to focus on my daughter.”

While living in New York, Ihab became very interested in outdoor activities like hiking, snowboarding, and biking. It was challenging in NYC to get out into nature. This changed in 2013 when he moved to Virginia, which has plentiful and easily accessible outdoor recreation opportunities.

Harrisonburg

When Ihab first moved to Harrisonburg, Virginia, it didn’t feel like a welcoming community, but that has since changed.

“I feel like Harrisonburg is becoming a good hub for the multicultural community. Once people know you they open their arms, but it takes a while. For the first couple of years, people weren’t welcoming. Locals are not used to foreigners that much. If you go to the countryside where my patients are from, they are not used to accents or different colors.”

Diversity

At the mosque he attends on Fridays, almost everyone is a refugee. In New York, he was used to meeting people in his community who were highly educated professionals. The Harrisonburg immigrant community is mostly farmers, taxi drivers, and factory workers. He believes this diversity within the community sometimes leads to cultural misunderstandings and has brought both good and bad to Harrisonburg.

“It’s like if you take a guy from West Virginia and dropped him off in India.”

Ihab is trying to get more involved in the Muslim community and local interfaith initiatives, especially after the election in 2016. He is happy that when local churches and synagogues gather, they invite the mosque now.

“We need to show we are part of the community and that we belong.”

Specialist

Ihab works as a dental surgeon at the hospital, primarily with geriatric patients, as well as covering the emergency room. In New York, he treated a lot of gunshot victims or people in traffic accidents, but here he is doing a lot of extractions.

“It’s not crazy here like it used to be in New York.”

When Ihab first moved to Harrisonburg, a lot of patients were referred to him because of his specialty. Some of them thought he was too young, and that they couldn’t trust him because of his accent and background. He would give these patients their treatment plan, but they would go to someone else for a second opinion – the local “American” doctor who grew up in Virginia. Ihab explains how it was funny because that doctor would usually say, “no, you need to go back to him [Ihab] – he’s the specialist!”

“They tried to run away from the Middle Eastern guy with an accent. Now a lot of those patients don’t want to see anyone but me!” (audio below)

When Ihab goes bow hunting in the countryside, he knows people look at him funny because of his appearance and accent. Today a lot of the locals know him as “The Jordanian.”

“The more time I spend here, the more bond I feel I have with the locals.”

Ihab has faced discrimination in Iraq and Jordan, so when he was leaving for the United States, he was worried. However, the country surprised him. The US is the place where he feels most at home.

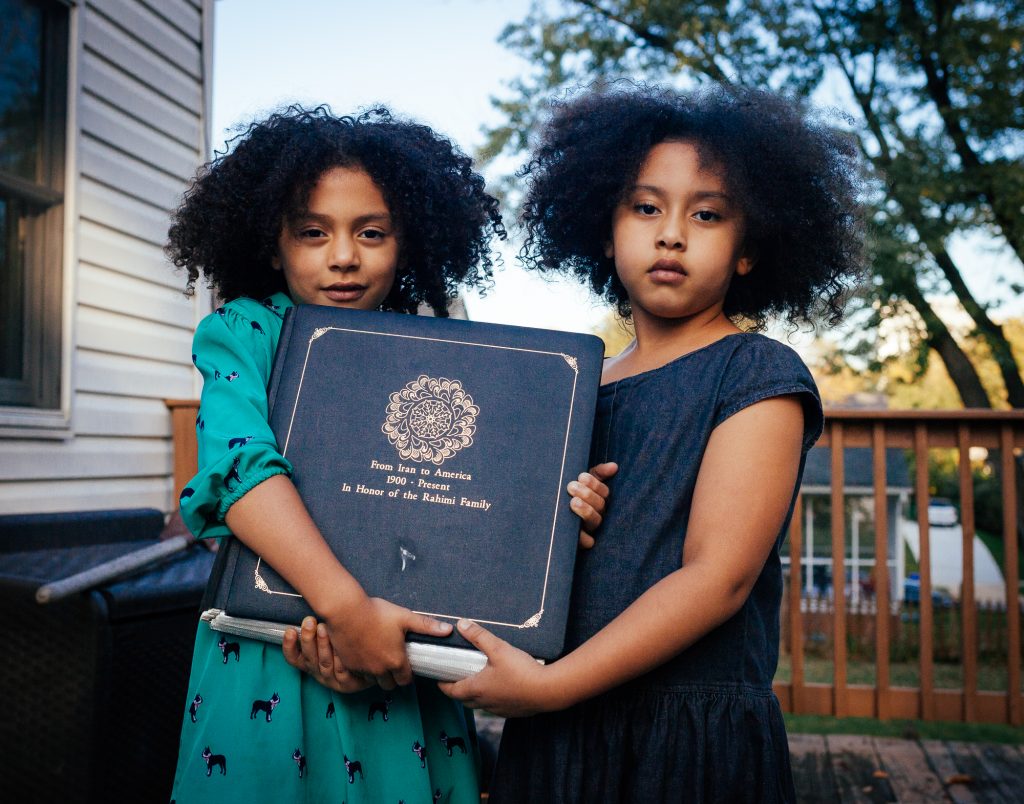

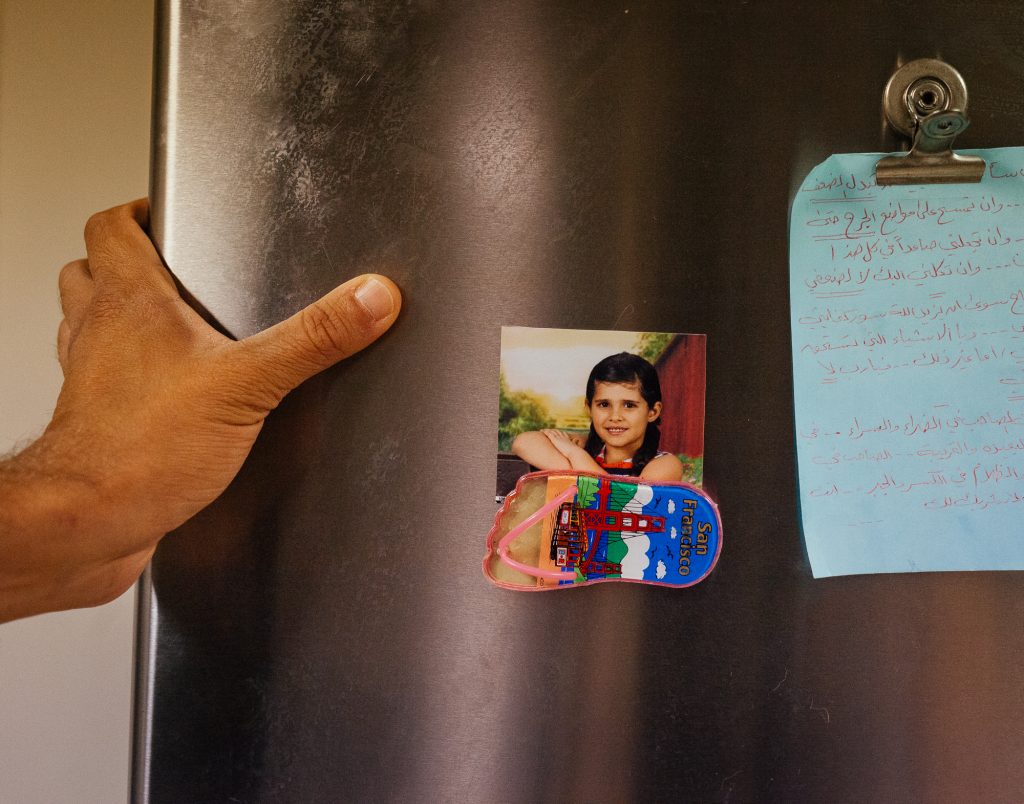

Daughter

Ihab didn’t plan on becoming a father when he did. At the time of his daughter’s birth, he wasn’t economically stable, and his marriage was already in trouble. He wasn’t sure he even wanted a child.

“To tell you the truth, my daughter is the best thing that ever happened in my life. She protected me from committing suicide. I had lots of pressure in my career and then the divorce. She is the only thing that makes me really happy.” (audio below)

Ihab has his daughter over every other weekend and for most of the summer.

“I wait so passionately for these days. This is my fun time. My daughter does everything I do – we bike together, we kayak together, we climb together. Being a father – I’m so blessed to be that guy. This little thing comes and isn’t planned and becomes the pleasure of your life.”

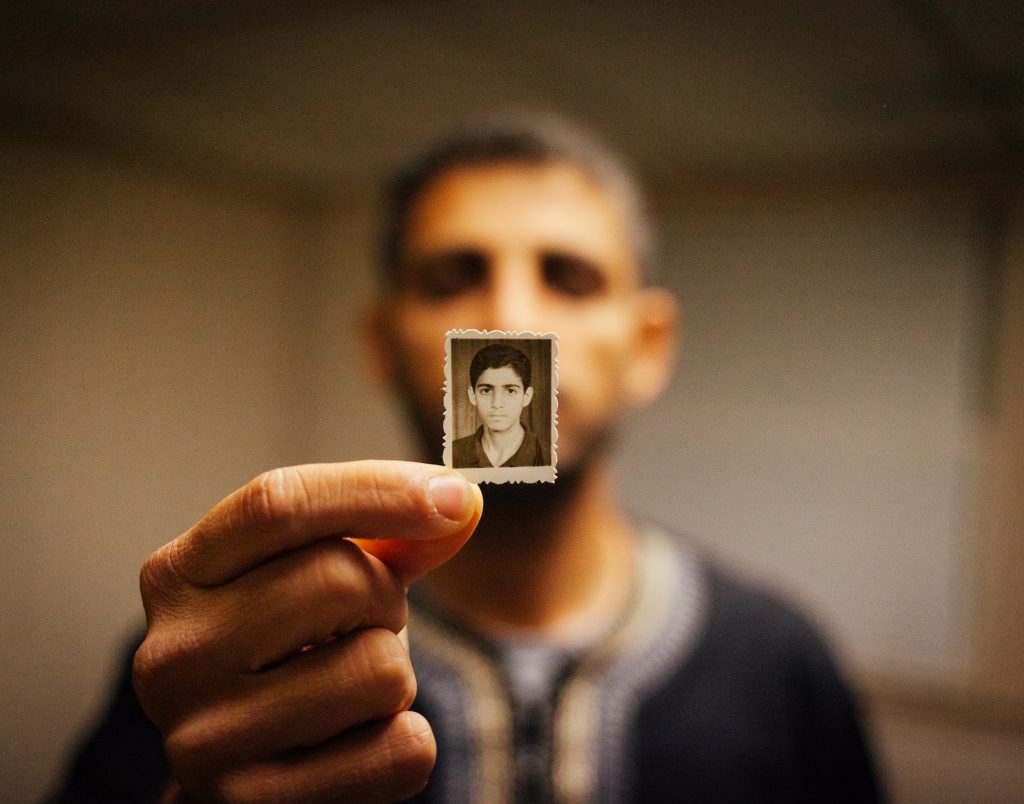

Father

Ihab hopes to set a good example for his daughter, like how his father did for him.

“My dad was my role model. He was always willing to help people. I just wanted to be like him.”

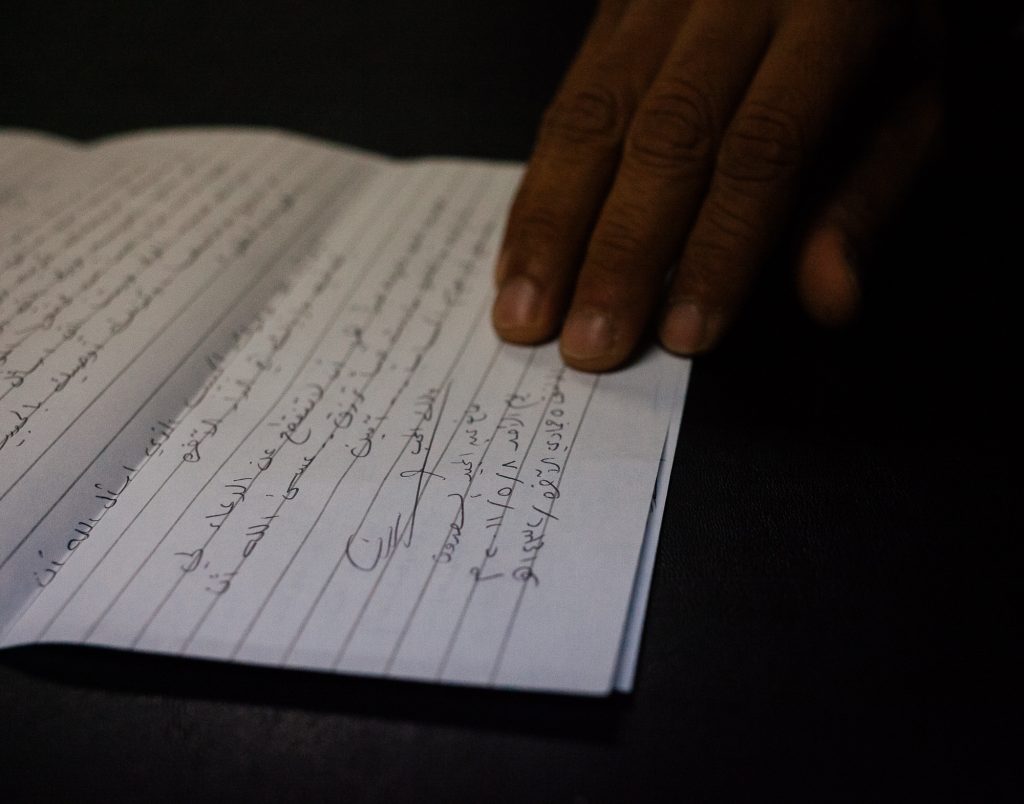

Ihab’s father came to visit him in Harrisonburg before he passed away in 2016.

“When I lost him, I was in Kenya on a mission trip. I was going to come back for his funeral, but if he were alive, he would have told me to go back and help people. This is what he would like me to do.” (audio below)

“This is a letter my dad sent me before he died. He asked me to open it after he died. He was writing his will. Every week I open and read it. ‘We are all going to die. Do good things and try to be good to family and your patients.’ He was a religious guy, so he wrote, ‘God will always take care of you.’” (audio below)

Travel

Ihab has traveled a lot. He has three passports filled with stamps.

“Every stamp has a story.”

India is one place that continues to have a lasting impact on Ihab. Even though people have so little materially, they seemed happy. It was shocking. He returned to America, knowing that instead of buying luxury items, that money could feed people in need. He subsequently began to donate to those who are less fortunate, and he buys only what he needs.

“India changed my lifestyle forever. I try not to be luxurious at all and try my best to remind those around me of this. I want to share this with his daughter.”

Future

Ihab is hopeful for the future. He used to be argumentative and willing to fight. Today, he believes if you speak softly, others will eventually understand you. In response to the current administration’s rhetoric towards Arabs and Muslims, many of Ihab’s patients have reached out with compassion to let Ihab know that they don’t believe what they hear from this administration about his people. They want Ihab to know that the president does not speak for them.

“Lots of immigrants don’t have a life anywhere other than here. They are more American than Americans themselves, because they don’t take it for granted. They are great assets for the American mosaic.”

“Regarding my future – the road is open. Sometimes I think about taking a few years off and going on medical missions. I don’t know what I’m going to do in my life. If I’m here in the US, I will help bridge the gap between the right and left of the aisle.”

Ihab says he doesn’t have many childhood friends because he didn’t live in one place long enough while growing up. This inability to stay put for long has continued into adulthood. Ihab has been in the US for a little over a decade and has already lived in four different states.

“I am living like a modern bedouin. I get bored and always find an excuse to move. I’m not sure how long I’ll stay in Virginia, but I’m definitely enjoying my life. There is lots of goodness in the people here. They try to be good neighbors.”

#FINDINGAMERICAN

To receive updates on the book release and exhibition of “Finding American: Stories of Immigration from all 50 States” please subscribe here. This project is a labor of love (and passion). If you would like to support the project’s continuation it would be greatly appreciated!

© Photos and text by Colin Boyd Shafer | Edited by Kate Kamo McHugh. Quotes edited for clarity and brevity.