“Our people have proved our resilience over and over again throughout history. The issue is not our resilience – the issue is oppression. Our resiliency is not permission for others to keep oppressing us.”

Jeepneys

One of E.J.’s earliest memories is of his dad driving a jeepney in Manila. Jeepneys are remnants of America’s military presence in the Philippines. They were left by Americans, modified by Filipinos, and are now the country’s primary form of public transportation. Starting at three years of age, E.J. worked as his father’s “barker” (the person sitting up front in the jeepney barking out to possible passengers on the street where they’re headed). He specifically remembers yelling out ‘highway, highway, highway!’.” (audio below)

E.J., his older sister, and their parents lived in a little shack with a bathroom, a kitchen, and a bedroom, where they all slept in one bed. But when E.J. turned four, his father moved to the United States to find work. By the time E.J. turned six, his family built a house in Las Piñas, a nice suburb of Manila, with the money his father sent home.

A lot changed in E.J.’s life at age nine when his parents divorced.

“A lot of the responsibility for trying to better my family fell onto me because it was my dad who left. I took that to heart, and I wanted to help my mom.”

USA is Better

From an early age, E.J. learned that the United States is a better country than the Philippines. E.J’s mother used to take him once a month to buy an action figure from the toy store. The price of almost every toy was negotiable, but his favorite, the American G.I. Joe was not. E.J says his mother, “the best bargainer in the world,” would try each month to bargain down the G.I Joe price, but she never won. All the sellers had to tell her was that the toy came from the USA. (audio below)

The idea stuck with E.J. – everywhere else has a lower value than the United States.

“The message I received as a kid is that anything made in the USA is more valuable, more precious, and better than anything made in the Philippines.”

Pizza & Honey Buckets

After leaving the Philippines, E.J.’s father settled in Barrow (as of 2016 it is Utqiagvik), Alaska, remarried, and started a second family. He worked at the post office, as a cab driver, and at a pizza place. E.J. remembers that job because whenever his father returned to visit them, he would make delicious pizza. After that job, his father drove the town truck that retrieved “honey buckets” (sewage).

“Disposing of human waste was the job that helped my family a lot.”

Carrying Crucifixes

At 14, E.J.’s parents decided to send him and his little brother to Barrow to join their father. E.J. remembers feeling excited – especially about a trip to Disneyland and Universal Studios – but he was also unhappy to leave his mother behind.

“My mom put her two very young children on a plane to cross the Pacific Ocean and go to a place she had never seen before. She didn’t even know if she would ever see it! She did this just because life would be better for my brother and me. That was a big sacrifice for my mother. In the back of my mind, I didn’t know when I would see my mom again, if ever?”

Aside from their checked bags, E.J. and his brother each carried a four-foot-tall crucifix as carry-on luggage. His dad had requested these from Pampanga, his home province – one for his house and one for the local Catholic Church in Alaska.

“We were walking in airports and onto airplanes carrying crucifixes all the way to Barrow, Alaska. It’s funny, but also symbolic. We were literally carrying crosses on our backs.” (audio below)

Los Angeles vs. Barrow

E.J. and his brother first arrived in Los Angeles, where their aunt lived. Even though their stay was short, she took them to Disneyland and Universal Studios. This initial experience set the bar high for what E.J. expected from this new life in the United States.

Barrow, Alaska contrasted drastically with Los Angeles, California – no paved roads and wooden buildings that sat on stilts to avoid melting the permafrost. E.J.’s dad took him for a drive around the remote town of about four thousand people. E.J. asked to go to the city to get some clothes. His father informed him that the only way in and out of Barrow is by plane!

Basketball

E.J.’s dream growing up in the Philippines was to one day become a professional basketball player. He believed it was the one way he could make enough money to help his mom. Luckily, basketball is popular in Barrow, and this helped E.J. adjust to life in the United States.

“Basketball kept me straight, away from trouble, and it gave me something to dream about. Basketball forced me to stay in school. To do well enough in my classes that I could remain eligible to play ball. In the process, I ended up doing pretty good in school!” (audio below)

Margaret

E.J. had been going to an all-boys school in the Philippines, but when he started middle school in Barrow, he had girls in his class. It didn’t take long before he noticed Margaret, who is Koyukon Athabascan (indigenous to Alaska). E.J. knows that Margaret’s fair-skin increased his initial attraction to her.

“I thought I was going to marry her, and we were going to have light-skinned kids together, and I could show them off to my Filipino family.”

Today E.J. recognizes the problematic origins of where the attraction to pale skins comes from.

“I grew up in the Philippines in a context where anything American is better than anything Filipino and being American is equated to being white, and anyone who is lighter skin is more attractive than dark skin folks. I grew up in a context when people were using skin whitening products – soap and bleach. People tell you not to go in the sun, and skin whitening clinics are everywhere.” (audio below)

They talked for the first time when E.J. asked to walk Margaret home. She let him walk her to the corner of the street, but no farther. E.J. reflects and laughs, “She didn’t want me to know where she lived!” E.J. and Margaret dated for a few years, broke up, then got back together in their senior year of high school. They’ve been together ever since.

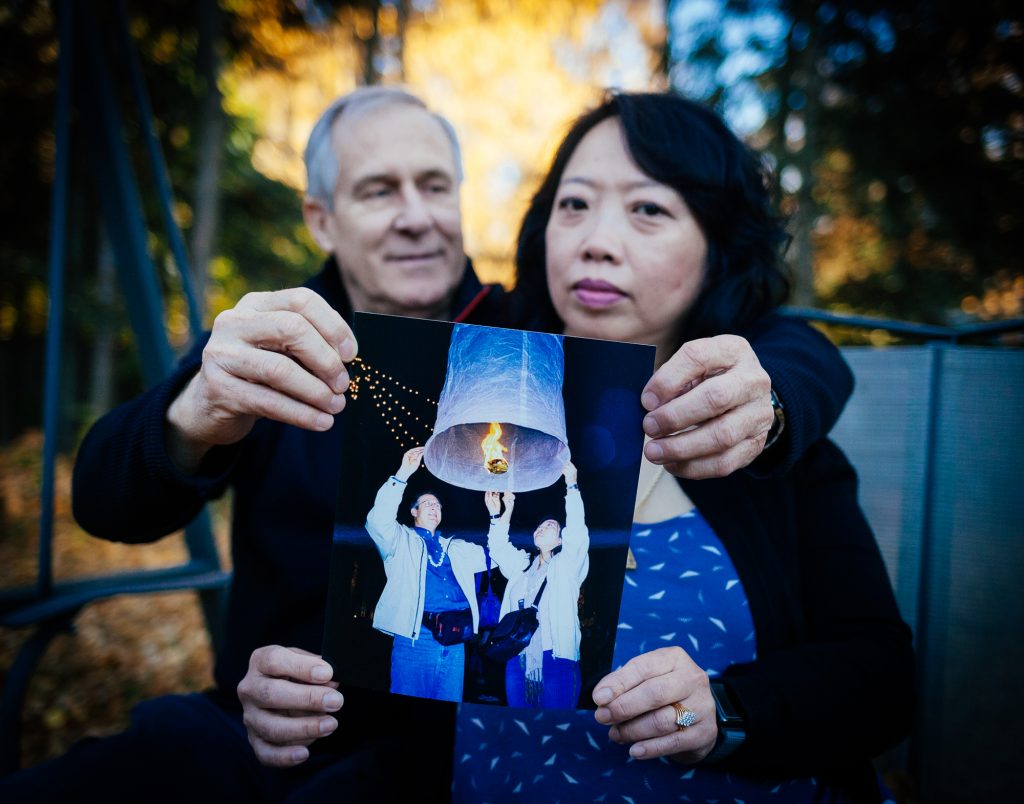

The Santo Niño

Two years after arriving in the United States, E.J. and his brother went to the Philippines to visit their mother. His brother decided he didn’t want to leave. The Santo Niño (Santo Niño de Palaboy) has always been important to E.J.’s mother. She prayed to it for a child, and then became pregnant with E.J. Then before E.J. left the Philippines the second time, she gave him a Santo Niño de Palaboy (known to watch over the homeless and those with nowhere to go) [see the above photo]. She hoped it would take care of her 16-year-old son, who was leaving her again, but this time without his brother. (audio below)

Homeless

E.J found it hard to live in his father’s house in Barrow, with his stepmom and step-siblings. He felt a lot of anger towards his father and consequently only went home when he had nowhere else to go.

“I ran away a lot and slept in friends’ homes and on couches. I spent my entire senior year of high school sleeping on my friends’ floor – I really didn’t have a home. Basketball was my home.”

Filipino

After arriving in Barrow, E.J. tried to become as American as possible. He watched a lot of Boy Meets World and Saved By the Bell – where he got a lot of ideas about how an American teenager should be. But Barrow, due to the Utqiagvik indigenous community, was different than the America depicted on these shows. Ironically, while watching this proud community resist the erasure of their language and culture, E.J. was trying to rid himself of his.

“Not only did I literally leave my country, but now that I’m here, trying to erase or hide the little bits or pieces that are hanging on to me. It got to the point where I was discriminating against other Filipinos.” (audio below)

In his junior year of high school, someone left an anonymous message on his locker: “You are Filipino. Act like it!” E.J. knew that they had a point and started to reflect on his behavior towards other Filipinos. He realized he was trying to lose his “Filipino-ness” when most of his family and friends lived in the Philippines.

“Have I abandoned them? Have I forgotten them? Why was I trying so hard to get rid of my accent and be ‘American’?” (audio below)

Without the questions that this note spawned, E.J. wouldn’t be doing the academic work he does today.

Alaskan Myths

E.J. knows that there are a lot of myths about Alaska.

“We don’t live in igloos, or swim with whales, or hang out with polar bears!”

One predominant myth E.J. often comes across is that Alaska isn’t a multicultural state. He explains how it is diverse not only because of immigrants but also because of the different indigenous groups in Alaska. Anchorage is exceptionally diverse. Some studies say the most diverse neighborhood in the country is in East Side, Anchorage.

Filipinos are the largest immigrant group in Alaska, and also the largest undocumented population in Alaska. E.J. explains how Filipinos have an expression for their undocumented population – “TNT” (Tago Ng Tago) – which translates to “always hiding.”

“Filipinos are virtually invisible when it comes to the national conversation about immigration and undocumented immigration.” (audio below)

E.J. believes many Filipinos aren’t vocal about this situation because they want to remain under the radar. Their priority is to continue being in the United States and supporting their family – not change laws.

Lucky Timing

E.J. didn’t grow up with a plan to go to college. As his dreams of playing professional basketball faded, and he found himself needing money, he enlisted in the U.S. Army after his junior year in high school. He planned to fly to Alabama and start basic training after graduation.

In E.J’s senior year, Alaska started a program where full scholarships to the University of Alaska were offered to the top ten percent of the state’s graduating class. E.J. found himself in that top ten percent and in a position he could never have imagined. He decided not to attend basic training, as planned, and instead started studying psychology at the University of Alaska Anchorage.

“I fell in love with psychology because it was helping me with my personal struggles. In eight years, I went from not going to college, to having a Ph.D.!”

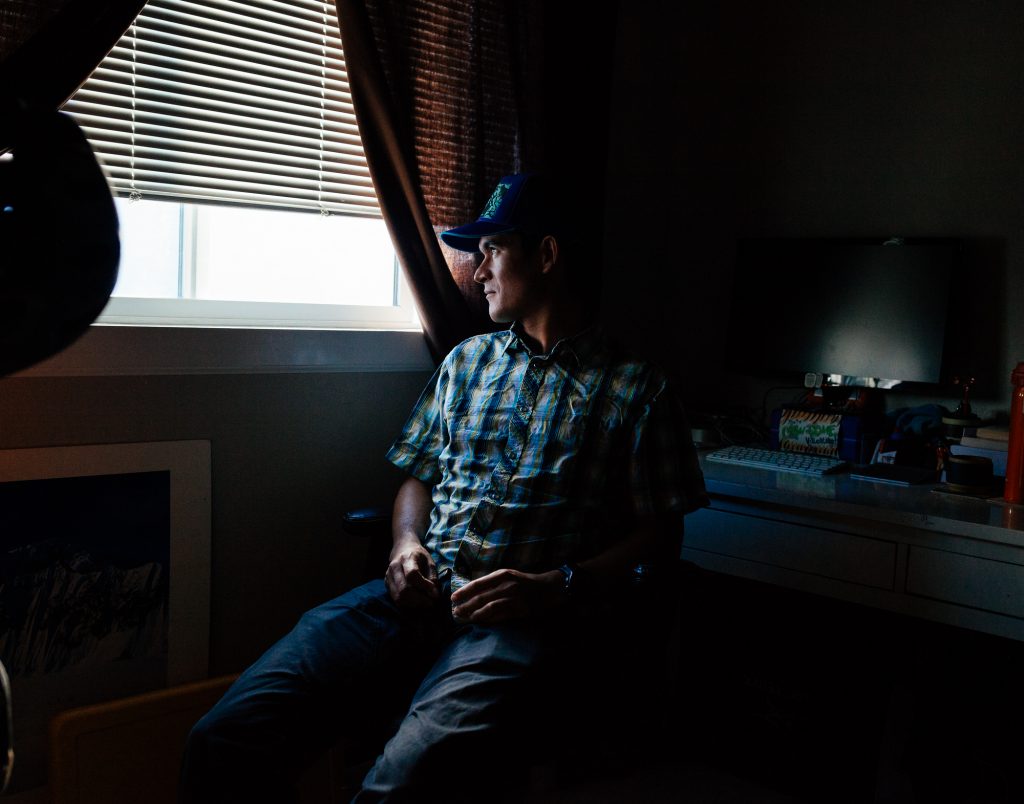

Academia

E.J. works as an associate professor of psychology at the University of Alaska Anchorage. His focus is on the effect colonialism has on how people think about themselves, their culture, and their mental health.

“I turned my personal experience into a career.”

“Internalized oppression” is central to E.J.’s research. When groups of people are repeatedly told that their language, worldview, traditions, skin color, etc. aren’t good enough, these messages eventually seep into their minds. You don’t need to tell them these oppressive messages anymore because they start telling themselves those oppressive messages. They start believing it.”

“I see [internalized oppression] with my people. Skin whitening products are all over the Philippines, and nobody questions it anymore. The English language is the language used in all of our schools in the Philippines. The message is that English is the language of education. In this case, the idea that American things are better than anything Filipino has been internalized and institutionalized. We have built institutions that reflect this oppression.” (audio below)

E.J. has published four books so far [see the above photo]. His most recent, We Have Not Stopped Trembling Yet (2018), is a series of letters to his Filipino-Athabascan family highlighting issues around colonialism, sexism, racism, and internalized oppression.

“Oppression is redundant; it is nothing new. Be ready, but please don’t get used to it. Don’t habituate to it, don’t put up with it, and don’t accept it. Be fed up with oppression. Be sick and tired of it, be angry, be outraged, be devastated by it. It’s natural to be distressed by something so violent and wrong. I have been devastated by it many times, in fact, I am even permanently damaged by it.” (audio below)

Paranoia

E.J. explains how Alaska is a “very red state” (that produced Sarah Palin) and the 2016 presidential election heightened E.J.’s fear and paranoia. At any time, he may be feet away from people who don’t want people like him around.

“Bigotry and racist ideologies and anti-immigrant sentiments have always been a part of America. These are stolen lands – especially here in Alaska. We are aware that those things have always been a part of this country – colonialism, racism, and cultural genocide.

On the positive side, E.J. believes the 2016 election encouraged more people to fight back and resist oppression.

Respect

E.J. thinks it is essential to include America’s indigenous peoples in the national immigration conversation. He feels like his mixed indigenous-Filipino family is at the intersection of the seemingly irreconcilable conflict between indigeneity and those trying to immigrate.

“As immigrants, we need to acknowledge the indigenous peoples of this land and work with them. Until this day, they are still fighting the oppression of their culture. As immigrants, it is our responsibility to pay respect to the people and respect the lands. The most important way we can respect indigenous people is to work with them to make sure these lands stay welcoming, and that injustice and oppression do not happen here.” (audio below)

E.J. believes people should be careful when repeating statements like “immigrants make America great” or “America is the land of immigrants.”

“We cannot advocate for immigrant rights at the expense of further erasing indigenous people.” (audio below)

Beyond Economics

E.J. also thinks it is problematic how society often judges immigrants solely on their economic value.

“We shouldn’t put a price tag on people’s humanity and dignity. We play into this system that says we are only valuable because we contribute this much money. Are immigrants any less of humans? We don’t do that with the native-born, so why are we doing that to the immigrants?” (audio below)

Colonialism

E.J. thinks it is important to question why people immigrate, and why life is better in one country and worse in another. A lot of answers lie in colonialism and exploitation. Unlike how a salmon instinctually swims upstream, humans aren’t naturally inclined to migrate.

“I wasn’t born with a ‘go to the United States instinct’ – to leave my family behind, and my culture. Nobody is born with an instinct to sacrifice everything you are familiar with. Why did I develop this dream along with so many others?”

E.J. explains how it becomes easier to understand why people want to leave the Philippines and move to the U.S. after one studies the Philippines’ complex history of resource and labor exploitation.

“I’m here because America went there first.” (audio below)

Creating Superheroes

E.J. & Margaret want their kids to grow up understanding their Koyukon Athabascan and Filipino heritage. While E.J. tries to share Filipino culture, Margaret shares her language, food, and the stories her parents told her growing about her people’s history. These stories grounded her, and she hopes they do the same for her kids.

“We try to tell stories, read stories, and talk about our family. They have the privilege of these different heritages. Along with that, they have this responsibility of figuring out how they want to help our community.”

E.J. wants them to see their own diversity as a privilege.

“I want my kids to use their roots and see them as their superpowers. Just because you have superpowers doesn’t mean you are a superhero. You have to use your superpowers for good, otherwise, you are a villain. I want my kids to be superheroes.” (audio below)

*Update: Since the interview, E.J. and Margaret have welcomed the newest member of their family, Tala Raine Nodoyedee’onh.

#FINDINGAMERICAN

To receive updates on the book release and exhibition of “Finding American: Stories of Immigration from all 50 States” please subscribe here. This project is a labor of love and passion. If you would like to support its continuation, it would be greatly appreciated!

© Photos and text by Colin Boyd Shafer | Edited by Kate Kamo McHugh. Quotes are edited for clarity and brevity.