Childhood

Mariya was born in 1990 in Yaroslavl, Russia – a large industrial city four hours from Moscow, famous for making rubber tires. Her father was finishing his Ph.D. and her mother was completing medical school, so it was her babushka (grandmother) who looked after Mariya.

It wasn’t easy for her parents to find jobs in Russia that fit their qualifications. Mariya’s mother was a doctor, but she ended up accepting a job at a blood bank. Her father was a software engineer but had to work two jobs plus teach at a university to make ends meet. Like many others, the post-Soviet era was a difficult economic time for her family. She remembers the uncertainty as to whether or not there would be bread available to buy.

“The milk truck would come once a week, and my grandma would wait in a line at nine at night to get milk for the next morning. It was bad. It’s hard to relay the bare bones of life in Russia.” (audio below)

Once a year at Mariya’s preschool, they would do school pictures with a stuffed animal, and the girls had to wear a bow in their hair. Mariya didn’t have a bow because her parents couldn’t afford it, so she had to borrow one. (audio below)

In school, Mariya always tried to be the best – she knew education was important to her parents. She didn’t have any other dreams or ambitions, though. The mentality was, “just do what you have to do.” This thinking changed at nine years of age when Mariya and her baby brother moved to the US with their parents.

“When we got to America, that’s when my parents told me to have big dreams. I feel like that was the American way of thinking about the future.” (audio below)

United States

All of her ideas about America came from the TV. They had three channels, and only one American show called Charles in Charge.

“There was a big house with a pool; everything was just so big and so beautiful. That was the only visual I had. I was going to move to the U.S. and have a big beautiful house and a big pool. Life was going to be great.”

In the late 1990s, many other families were leaving Russia for California and Silicon Valley’s technology boom. People in software engineering, like her father, were leaving Russia because of the lack of available jobs. She remembers being excited about her first plane ride.

“When you’re young, you don’t understand the gravity of what you are about to do – literally, leave everything you know behind.”

In hindsight, she realizes how little her family knew about where they were going.

“We didn’t know the geography of where we were going. My dad used to say, ‘We are going to live in San Francisco, but I’m going to work in L.A.’ We thought the cities were right next to each other!” (audio below)

Mariya’s family left Russia with giant bags because they couldn’t afford suitcases and $100 cash from Mariya’s uncle. When they got to California in 1999, they borrowed money and moved into a Walnut Creek apartment. Walnut Creek, was an area where many other Russians immigrated to. It wasn’t the affluent place it is today. Their new apartment was on the second floor, and from the balcony, Mariya could see the complex’s pool and fountains.

“To me, it was like we were living in a resort; I had never seen anything like this in my life.”

Soon the novelty faded away, and Mariya, age nine, realized that life wasn’t going to be easy in the US. She was confused by how empty the streets were – “where are all the people?” In Russia, she walked or took public transportation. In America, she realized that everyone drives, and if you are going to walk somewhere, it will take you a long time.

Within a couple of days of arriving, Mariya started school. It was the spring, almost the end of the school year, but her parents still made her go. She had studied English in Russia a little, but it was British English. Instead of saying “mom” or “dad, Mariya said, “mother” and “father” (in a British accent). Mariya realized that the English she knew wasn’t going to help much. Mariya was lost.

“I was sitting there in class, not understanding anything that was happening. And then I would go home at night with homework that I was responsible for completing. At home, my mother and I would translate every single word with a dictionary.”

Mariya went from being a top student in Russia, to barely scraping by. She remembers crying to her mom, telling her that she wants to give up. Luckily, things got better over time. Looking back, she knows it was much easier for her than for her parents to transition to life in America since they knew no English at all.

Synchronized Swimming

In that first year of being in the US, Mariya brought home a flyer advertising a two-week crash course in synchronized swimming. Back in Russia, she had done swimming and gymnastics but had never tried “synchro.” Her mom thought it would be an excellent way for her to do something other than schoolwork, make friends, and practice her English. Mariya took the crash course, and when they asked her if she would like to do this year-round, she said “yes”!

“When you’re young, synchro is appealing because you’re swimming, but you are also dancing in sparkly suits and makeup. It combines a lot of aspects into one sport. You do gymnastics and acrobatics, you go upside down, and a lot is going on. I loved being in the water and doing something artistic.”

She was with the Walnut Creek Aquanuts from the end of elementary school to high school. With each passing year, she got better and more competitive. It was a financial strain on her parents, but they always supported her.

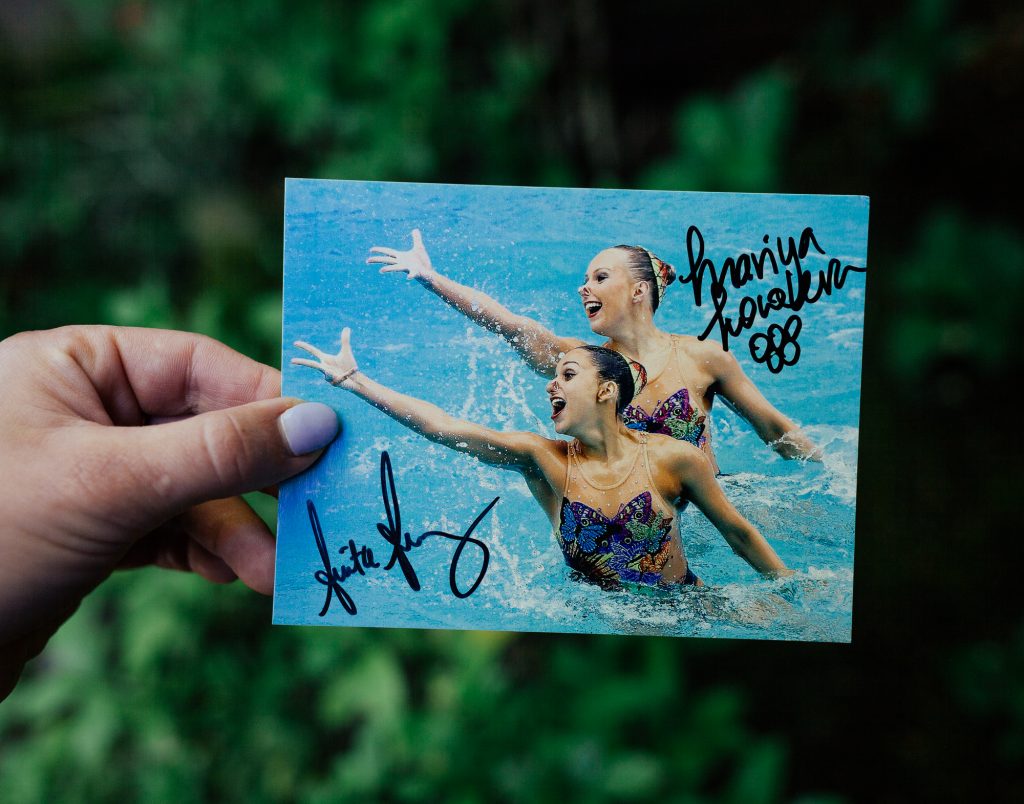

In her junior year of high school, Mariya became a US citizen, so she tried out for and made the US Junior National Team. As she neared the end of high school, Stanford University was her number one choice. Still, Mariya doubted that she would be accepted there. Luckily, being recruited as an athlete improved her chances, and she got in. While at university, Mariya started her career with the US National Team, and in 2012 she went to the Olympics in London.

Olympics

Mariya finds it hard to put into words the pride she felt representing the US.

“In the Olympics, you feel like you are a part of something bigger. I’m not just in my little sport. The US Olympic & Paralympic Committee does an excellent job of creating camaraderie. I remember getting my first USA jacket and feeling so proud.” (audio below)

“The Olympics is like nothing you’ve ever experienced before as an athlete. It’s a crazy experience, but the most amazing experience I probably will ever have in my life. It’s the entire pinnacle of the work you’ve done your whole life. The pressure you feel is immense, even if you go into the Olympics knowing that you’re not going to get a medal.”

Mariya explains how in synchro, it’s like you are training your entire life, for only nine minutes of actually competing. The pressure of having the whole world watching is like nothing else. It is a struggle for many Olympic alumni because they will never be able to replicate that exhilaration and adrenaline ever again.

Russia has been the best in synchronized swimming for decades. When Mariya started synchro, she told her American coach that she wanted to swim for Russia someday. Legally, as a dual citizen, she could represent Russia, but deep down, she knew they were “light years” ahead of her. The training in the US isn’t what it is in Russia. She has never felt like it was a competition; instead, she is proud of Russia.

“I always felt pride listening to the Russian national anthem and watching the flag go up, but I also feel proud listening to the US national anthem. I was always even in my pride and allegiance, and it was hard for people to understand that. Their impressions seemed to sound like, ‘Well, you live here – you’re an American. How can you have allegiance to your old country?’” (audio below)

Mariya knows some immigrants abandon their culture when they come to the US and try to be as American as possible, but her family was never like that. They ate Russian food, spoke the Russian language, and she continued to be proud of her country of birth while representing the US. (audio below)

Returning to Russia to compete for Team USA was a special experience for Mariya.

“It was like coming home. When you walk out on deck they show your name and who you are competing for. When the Russian audience saw my name, which is clearly Russian, they all started cheering.” (audio below)

After her first Olympics in 2012, Mariya had one more year at Stanford and didn’t plan on returning to the Olympics again. After graduating, however, she started training and decided to try out for the National Team again. She was told she was too old to improve and needed to lose some weight – they would rather focus on younger teenage athletes. She felt insulted.

“Synchro being an aesthetic sport means that you’re always criticized. The pressure that comes with ballet, swimming, and gymnastics was strong. I am constantly criticized all day: ‘You’re doing this wrong – you’re doing that wrong. You also have to lose five pounds. Are you sure you want to eat that?’”

Her parents were okay with her retirement and figured it was a good time for her to get a real job and have an everyday life. Mariya, on the other hand, yearned for a second Olympic experience and would not give up. She returned to her home club in Walnut Creek to prepare for tryouts one last time. That next year at the national team trials, Mariya was the best swimmer there.

“You can’t keep someone off the team when they are number one!”

A year later Mariya was going to the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro.

“That was my redemption story. You told me you didn’t want me and I came back, made all the improvements, and proved you wrong.” (audio below)

After Synchro

The 2016 Olympics was a great way for Mariya to finish her career in synchro. In 2012, she finished 11th, and in 2016, they finished 9th. She was happy with the improvement and felt like she ended on a high. Throughout her synchro career, Mariya was always doing something outside of the pool. Towards the end, she was working part-time and finishing her Master’s of Sport Management at the University of San Francisco.

“My parents emphasized that I always had to have something to fall back on. There are tons of athletes that finish their athletic careers and have no education or work experience to fall back on.”

Her family has now been in the US for more than two decades. Mariya is confident that it hasn’t been what her parents expected, but she knows they don’t regret coming. She also knows her parents had no idea their daughter would become a US Olympic athlete.

“Some parents push their kids towards the Olympian path, but my parents just wanted a better life for themselves and their kids.”

Many people are surprised to find out Mariya wasn’t born in the US. With all of the political issues in the news regarding the United States and Russia she overhears a lot of discussions, and finds it hard to keep quiet.

“It is interesting to hear people speak their true feelings about Russia when they don’t know I’m from there.”

Mariya appreciates that she lived in another country, and she wishes more Americans would have this experience. From the moment she arrived in the US, it bothered her how little Americans seemed to know about other countries, like Russia.

“Once you travel and meet different people you start to understand that the way things are here is not the way they are other places in the world” (audio below)

Future

Mariya is nervous about the relationship between the US and Russia. She knows the US media shows things one way, and the Russian media shows them another way. All Mariya wants to see is peace. She is a dual citizen, and she can remain one unless the two countries are at war. If they did ever go to war, she would need to choose.

Currently, Mariya works for Visa and coaches synchro. Mariya hopes that eventually, she can put her Master’s in Sports Management to use and work more closely with athletics – specifically the Olympics. In the not too distant future, she would like to get married and start a family.

“I feel like I got started later than everyone because of synchro.”

#FINDINGAMERICAN

To receive updates on the book release and exhibition of “Finding American: Stories of Immigration from all 50 States” please subscribe here. This project is a labor of love and passion. If you would like to support its continuation, it would be greatly appreciated!

© Photos and text by Colin Boyd Shafer | Edited by Kate Kamo McHugh. Quotes edited for clarity and brevity.